THE ORIGINS

This section discusses the origins of the FMHS from the time Auckland University College was set up in 1883 until the Government approved the formation of a medical school in Auckland in 1964.The Origins

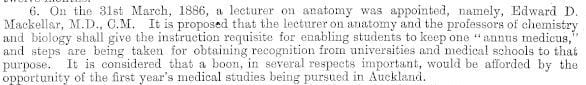

In his centenary history of the University of Auckland Keith Sinclair noted that in 1883 the newly-established Auckland University College had considered establishing a medical school, though the idea soon fizzled out. Instead, as the Education Department reported in 1886:

It is proposed that the lecturer on anatomy and the professors of chemistry and biology shall give the instruction requisite for enabling students to keep one `annus medicus’, and steps are being taken for obtaining recognition from universities and medical schools to that purpose. It is considered that a boon, in several respects important, would be afforded by the opportunity of the first year’s medical studies being pursued in Auckland.

Many of those who undertook those courses prior to World War I elected to complete their medical degrees overseas rather than transfer to the Otago Medical School.

When the tenth Australasian Medical Congress was held in Auckland in 1914, Auckland surgeon Arthur Challinor referred in his presidential address to the inevitability of a medical school for Auckland, to rival Dunedin, `ere long’. With war on the immediate horizon nothing came of the suggestion.

A decade later The Kiwi, the official organ of the Auckland University College Students’ Association argued that each of the component colleges of the University of New Zealand should be granted a separate Charter, arguing that:

Each University could then develop as it pleased, and increase its faculties as circumstances allowed. Our School of Engineering would at once be recognised, and our budding engineers could complete their course without leaving Auckland. At first our medical students would still have to go to Dunedin: but there would be nothing to stop us from founding our own Medical School as soon as finances permitted.

This prompted no immediate response but was revived by a number of MPs in the early 1940s, partly as a result of the shortage of doctors occasioned by the absence of many doctors caught up in World War II. Perhaps the most surprising support came from Dr David McMillan, a Dunedin medical graduate and general practitioner, who served as MP for Dunedin West 1935-43 before returning to medicine. In August 1941 McMillan urged the desirability of setting up a second medical school, noting that Auckland would be a good location since it had the clinical material for such a venture.

In July 1942 Henry Mason, an Auckland MP and Minister for Education, poured cold water on the proposal, announcing `It was no light matter to speak of the institution of a medical school, and very hard to do at the present moment.’

Despite ongoing debate, the establishment of the Auckland Medical School was still more than two decades away.

When Minister of Education Sir James Parr, a former Mayor of Auckland, helped lay the foundation stone of Otago’s new Medical School in 1925, he commented:

“No doubt Auckland’s day will come, but not yet.”

It was to be a long wait.

Jack Sinclair

Jack Sinclair, appointed as inaugural Professor of Physiology in 1968, was the brother of historian Keith Sinclair. Keith was inducted into the Mt Albert Grammar School Hall of fame in 1997 and Jack in 2004 (along with Professor John Scott). In a 2008 interview Sinclair recalled discussions around the Auckland Medical School in 1943.

After completing his medical degree at Glasgow in 1877, Edward Mackellar spent three years working in India before his appointment as house surgeon at Auckland Hospital in February 1883. He resigned in November 1883 because of `continual conflict’ with other officials and promptly accepted the position of lecturer in pathology and morbid anatomy in the University of Otago, though it appears he never took up the post.

Instead Mackellar became medical superintendent of Wellington Hospital, while still harbouring academic ambitions. When the Auckland University Council discussed establishing a medical school in January 1884, Mackellar advised a cut-price approach, advocating the appointment of only a lecturer in anatomy, who would work in tandem with the professors of chemistry and physiology. The proposal failed to gain support at this stage but was revived in March 1886, with Mackellar appointed to teach anatomy as `the initial step to providing for the first year or two of medical study in connection with the Auckland University College’. His credentials were no doubt enhanced by his marriage in 1885 to the widowed Mrs Mary Kissling, matron of Wellington Hospital and formerly head nurse of Auckland Hospital; her father, Colonel Haultain, was a member of the AUC Council.

Mackellar’s tenure was short-lived, partly because of ongoing tensions with the Auckland Hospital and Charitable Aid Board over the provision of a dissecting room.

Auckland University College was initially housed in the old parliament building, often referred to as `The Shedifice’. Constructed in 1854, this was demolished in 1917 to enable the laying out of Anzac Avenue.

The Otago Daily Times of 5 February 1887 publicised Auckland’s desire to establish a medical school and highlighted the tensions between the respective centres in Dunedin and Auckland.

The Medical Intermediate

The opportunity from 1886 to complete the medical intermediate year at Auckland rather than Dunedin proved popular with local students, many of whom went on to complete their education overseas, often at the prestigious Edinburgh Medical School.

One of those to take this route was James McMurray Cole, an Auckland Grammar School boy like so many others, who attended chemistry lectures and practical classes from 1910-12. A note on his record states: `kept terms 3 years but did not pass final BSc in 1912. Worked for cert of prof in chemistry in 1913.’ The following year Cole departed for Edinburgh, with the student publication The Kiwi keeping tabs on his progress. In August 1917 the magazine reported that Cole had passed his third professional exam but had been refused by both army and navy for war service. He graduated MB ChB in 1918 but did not return to practice in Auckland until 1923.

Cole has been singled out here because of his family connections with the University of Auckland; he was the father of David Cole, second dean of the Auckland Medical School from 1974-89.

In 1917 Douglas Robb, universally accepted as the father of the Auckland Medical School, followed in Cole’s footsteps. In February 1917 Robb was photographed with five fellow students who completed their medical intermediate year at Auckland University College prior to entering the full medical course at Otago.

Only four of them went on to graduate in medicine. Robb, the son of the General Manager and Chairman of the Kauri Timber Company, and Alexander Kirker, whose father was General Manager of the South British Insurance Company, graduated in 1922. Both were Auckland Grammar boys. William Blomfield, son of the famous Observer cartoonist and a former King’s College head boy, qualified in 1923 and Morice Greville in 1924. Kirker had been deflected from his planned study in London by the advent of World War I and two of the others were also affected by the war.

John Canning Dove, another King’s boy, joined the NZEF Rifle Brigade as a medical student, sailed for Europe in April 1918, and was killed in action in France on 26 October 1918. Harald Isaachsen, of Danish and Norwegian descent, was called up for war service in October 1918, a month before the Armistice. He survived but there is no evidence that he ever started his medical studies.

A seventh medical intermediate student was omitted from the photograph, for reasons unknown. Elsie Thorp was the daughter of a pioneering Paeroa farming family, which included a number of schoolteachers. Elsie passed her teachers’ exams in 1915, before medical intermediate, but there is no evidence of her later returning to the classroom. It appears that neither did she pursue her medical studies, dying a spinster in 1974 in Papakura.

JM Cole (back row, centre) featured on the Autumn 2008 cover of Ingenio. His presence was spotted by his son, David Cole,Dean of the Auckland Medical School 1974-89, who wrote to the editor: `Thank you for this reminder – it is one of the few good photos we have.’

Auckland University College medical intermediate students, February 1917. (left to right): HE Isaachsen, AH Kirker, JC Dove, WA Blomfield, GD Robb, M Greville

Branch Faculties

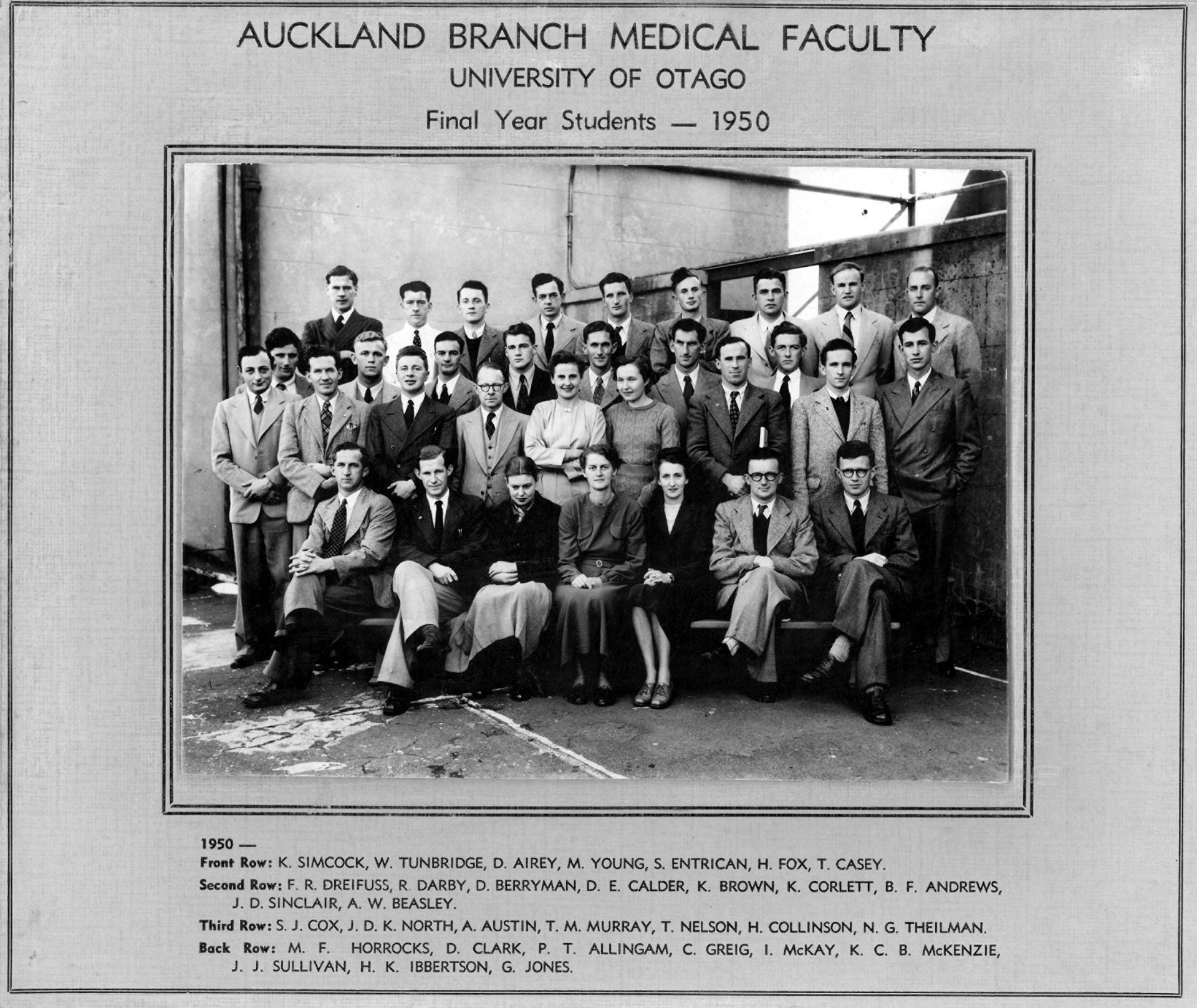

In 1937 the Otago Medical School established Branch Faculties in Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch, enabling final year medical students to gain clinical experience in the other main population centres. The scheme survived until 1972, by which time Auckland had its own final year students in place.

Many of the 1968 inaugural intake to the Auckland Medical School were born in 1950, a year which brought a crop of 32 final year medical students to the city to complete their studies. Among them were several who were destined to have a profound impact on the nascent Medical School. They included three future professors – Jack Sinclair (2nd row, 2 from right), Kaye Ibbertson (back row, 2 from right) and Derek North (3rd row, 2 from left), who also became the third Dean from 1989-92.

The class also contained five women, clustered together in the centre of the photograph. They included Keitha Farmer (née Corlett) who became a well-known Auckland paediatrician and Shirley Entrican, whose entry to medicine had been a protracted one. Entrican stood for election to the Auckland University Council student executive in August 1937, drawing the following comment from the student magazine Craccum:

`Always cool, calm and collected, Miss Entrican is a lady of many qualities, and has the clear thinking brain of a third year History student.’ Twelve months later she was elected as the female Vice President, before ultimately turning to medicine.

Postgraduate School of Obstetrics and Gynaecology

During the 1941 parliamentary debate in which Dr David McMillan suggested Auckland as the location for a second medical school, Mary Dreaver, a minister of religion, journalist, broadcaster, former Auckland Hospital Board member, and Labour MP for Waitemata 1941-3, took the opportunity to put forward the notion of an obstetrical school in Auckland. Dreaver gained cross-bench support from Cyril Harker, a Hawke’s Bay lawyer and National MP, who had successfully defended a local abortionist at four separate trials.

The advocacy of MPs must have been music to the ears of Dr Doris Gordon, the founder of the New Zealand Obstetrical Society in 1927. Gordon had already discussed the idea of a postgraduate school of obstetrics and gynaecology for New Zealand during a visit to Britain in 1939, enlisting support from the New Zealand expatriate, John Stallworthy, Nuffield Professor of Obstetrics in Oxford.

As part of her campaign Gordon persuaded Douglas Robb and two Auckland obstetricians – Tom Plunkett and Geoff Fisher – to help fund a visit to the country in 1943 by Sir William Fletcher Shaw, president of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Two decades later, in 1965, New Zealand obstetricians established a prize in honour of Plunkett, a prize which is still awarded annually to the Auckland MB ChB Part VI student who has achieved the highest marks in the study of obstetrics and gynaecology.

The location of the postgraduate school was central to the 1940s campaign. Doris Gordon had been informed that `the Auckland financiers would prefer to see money for medical purposes handled by Otago [rather] than administered by the AUC [Auckland University Council] as that body was too reformatory and employed too many pacifists, leftists etc on its staff for their liking’. Nevertheless, she and her ally Dr Douglas Robb, pressed for the chair to be attached to Auckland.

Debate about the location was heated when the matter came before the University of New Zealand Senate in 1946 but despite the efforts of three Otago representatives who `violently resisted’ allocating the chair to Auckland the motion was passed and, as historian Keith Sinclair later commented: `Otago’s monopoly of medical education was broken.’

Dr Doris Gordon (1890-1956) who vision and persistence put in place the first piece of the jigsaw which would in time become the Auckland Medical School.

South African-born Gerald Spence Smyth (1904-75), appointed to the Chair of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in 1951, was Auckland’s first medical professor. Smyth resigned in 1954, disillusioned with the lack of resources:

“I would take great pleasure in directing an academic unit if one existed.”

The Genesis of a Medical School 1947-64

During a parliamentary debate in August 1947 Duncan Rae, MP for Parnell, noted the recent institution of a chair of obstetrics in Auckland, which he regarded as `virtually a new medical school in the North’. Shortly thereafter Horace Smirk, professor of medicine at Otago 1940-68, wrote to Douglas Robb that he thought there should be two complete medical schools in New Zealand, when the population had increased sufficiently.

By 1953 the country’s population had topped 2 million, up from 1.8 million in 1947 and the University of New Zealand had approved in principle a second medical school in Auckland ‘when it is required’. This went against the wishes of Sir Charles Hercus, Dean of the Otago Medical School, who had, according to Rae, made a spirited plea for an extension of facilities in Dunedin. As Rae reminded Parliament, Auckland already had `the beginnings of a medical school – the very elementary beginnings’ with the appointment in 1951 of Gerald Smyth as Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

The breakthrough came in 1961 with the dissolution of the University of New Zealand and the creation of an independent University of Auckland. As Douglas Robb wryly commented in his memoirs: `Senate finally willed the second Undergraduate School to Auckland, but died 3 years before a date was fixed for its inauguration.’ Robb, ever a visionary, spelled out his hopes for the new venture in the New Zealand Medical Journal the following year:

`The foundation of a new school of medicine is a considerable event in any place and at any time. Dare we think of Salerno, Padua, Leyden and Edinburgh in a country such as ours, so remote in place and time?’

Robb also warned that Auckland would have to take into account the changes of the past 30 years in deciding `what medical teaching will need to be like’, and the requirement to consider the `social and cultural developments in which the school will work’, as well as the relationship with the University. He noted that many medical schools had little or no connection with a university, something he vigorously opposed.

Further delays over the choice of site and medical workforce requirements saw the government, the university and the University Grants Committee blame one another. Finally, in November 1964, Education Minister Arthur Kinsella gave the green light for the scheme to proceed. Douglas Robb had been the New Zealand correspondent for The Lancet for many years, and the journal responded to the news with the following tribute:

`Sir Douglas Robb, FRCS, has long had his heart and mind in the project, whose realisation will be largely the result of his efforts.’

Commentary by Jack Sinclair, inaugural professor of physiology 1967-93, on his recollections as a final year medical student in 1949-50.

Jack Sinclair

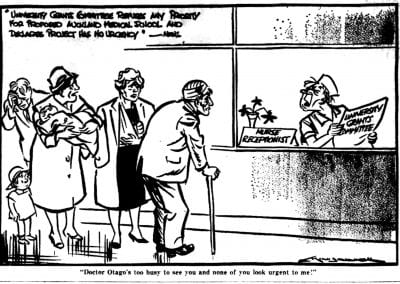

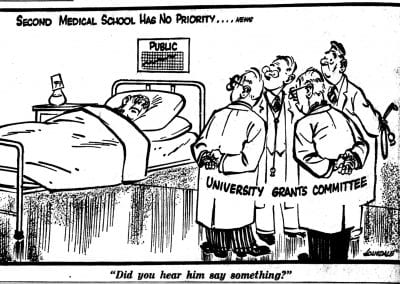

The local newspapers, the New Zealand Herald and the Auckland Star were in no doubt that the delays in establishing the Auckland Medical School were down to the University Grants Committee, as demonstrated in these cartoons, both published on 19 December 1962.

Douglas Robb: Father of the School

From the 1940s onwards Douglas Robb was a prolific writer on health reform in New Zealand. His publications from this era were adorned with an engraving of a tall, stooping figure scattering seed from a basket. Designed by Archibald Fisher, Director of Auckland’s Elam School of Art, this represented the Biblical proverb, `Behold a sower went to forth to sow.’

Robb’s projects, including the Auckland School of Medicine, bore fruit in part because of his extensive network of contacts, nourished from his time as a student. In 1917 when Robb attained the status of University National Scholar and first attended Auckland University College it was in the company of Percy Veale, a future scientist. Half a century later Veale’s son Arthur became the inaugural professor of community medicine at Auckland. Another contemporary, who sat the scholarship examination alongside Robb, was Horace Scott, father of John Scott, head-hunted by Robb to join the new School.

John Scott later recalled that as a child in the 1940s his mother had given him

pamphlets written by some slightly left-wing or more radically left-wing [people], including the late Alice Bush, paediatrician, the late Douglas Robb, later Chancellor Sir Douglas Robb, Sir Edward Sayers. They wrote a lot of pamphlets all foreshadowing a medical school, and lots of radical semi-socialistic changes in the health service which came to pass. So I was indoctrinated in that.

A third personal contact gathered into the fold was thoracic surgeon David Cole who had trained under Robb at Green Lane Hospital in the 1950s and in 1957 took over from him as secretary of the Postgraduate Medical Committee, founded in 1943 at the instigation of Robb and Green Lane physician Edward Roche. In his 1967 autobiography Robb predicted that the committee `will become part of the Faculty of Medicine when that is set up’. It is unclear whether he also envisaged Cole eventually taking over as Dean of the Medical School, which occurred in 1974, the year of Robb’s death.

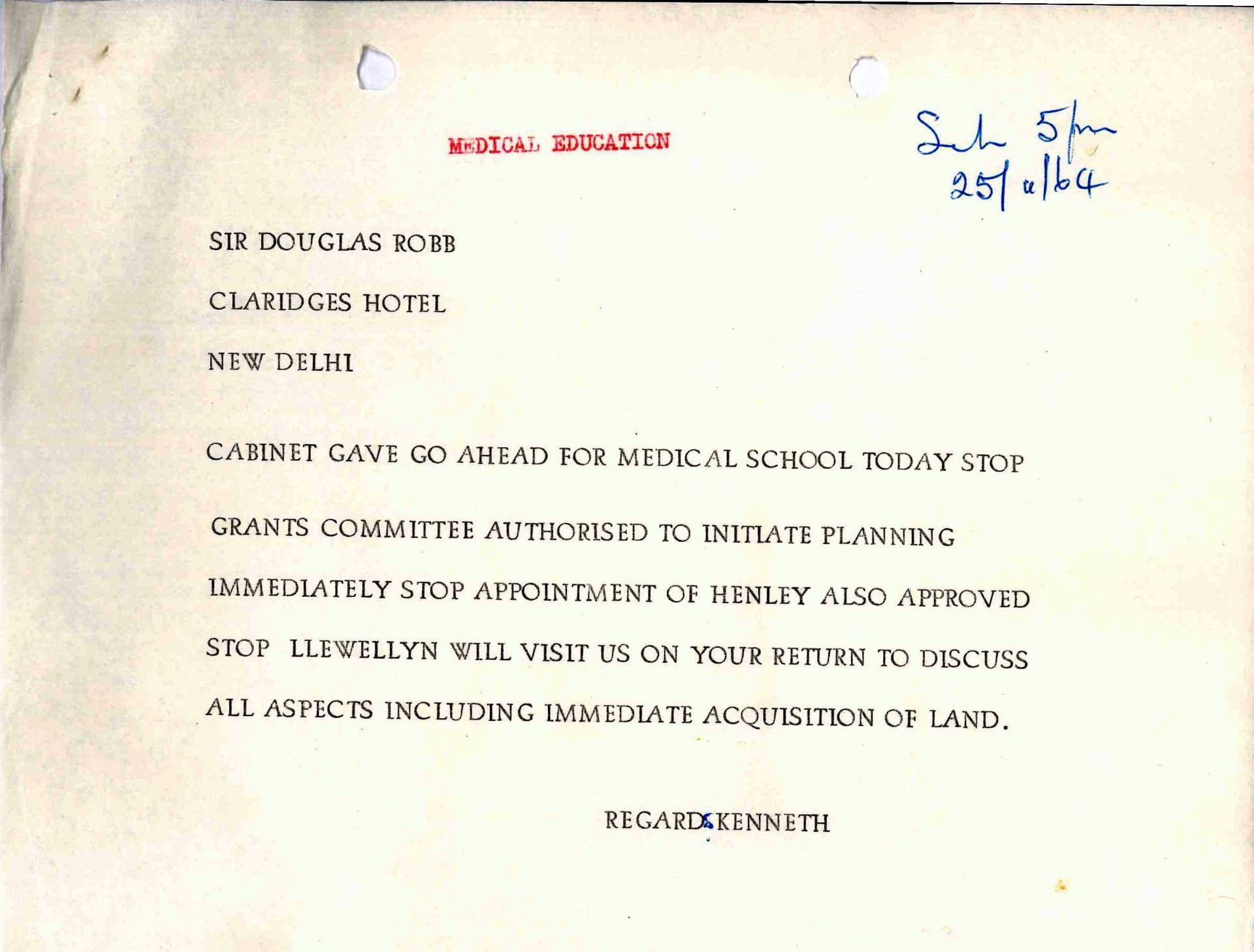

Robb’s unswerving faith in the prospects for the Medical School was rewarded in November 1964 when Auckland Vice-Chancellor Kenneth Maidment sent a telegram to Robb, currently visiting New Delhi on behalf of the WHO to evaluate the new All India Institute of Medical Science. Maidment revealed that Auckland had been given the green light, news confirmed that same day in a second telegram from Lady Robb: `Government approves Auckland Medical School congratulations darling all well.’

A few days later Robb wrote to another of his contacts, the highly-regarded Auckland botanist Lucy Cranwell, who had been resident in America for the previous two decades, about the culmination of the campaign which he had pursued for a quarter of a century:

I will send a report about it and would value your comments. We are in good heart about all this.

Wilton Ernest Henley (1907-81)

Wilton `Chook’ Henley, Superintendent-in-Chief of the Auckland Hospital Board 1961-73, was a central figure in the establishment of the Auckland Medical School. The son of a Napier doctor who died in the 1918 influenza epidemic, Henley began his medical studies in Otago before transferring to Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar, graduating in 1935. In 1959 he was appointed sub-dean of the Otago Medical School Branch Faculty in Auckland, a position which he relinquished in 1961 when he was appointed Superintendent-in-Chief. Twenty years later, one of his obituarists noted that the `potentialities of the position were immense, as it was likely that Auckland would eventually be given planning permission to have a medical school’. Another colleague commented at Henley’s funeral service that:

An obligation a Rhodes scholar accepts is `to esteem the performance of public duty as the highest aim’.

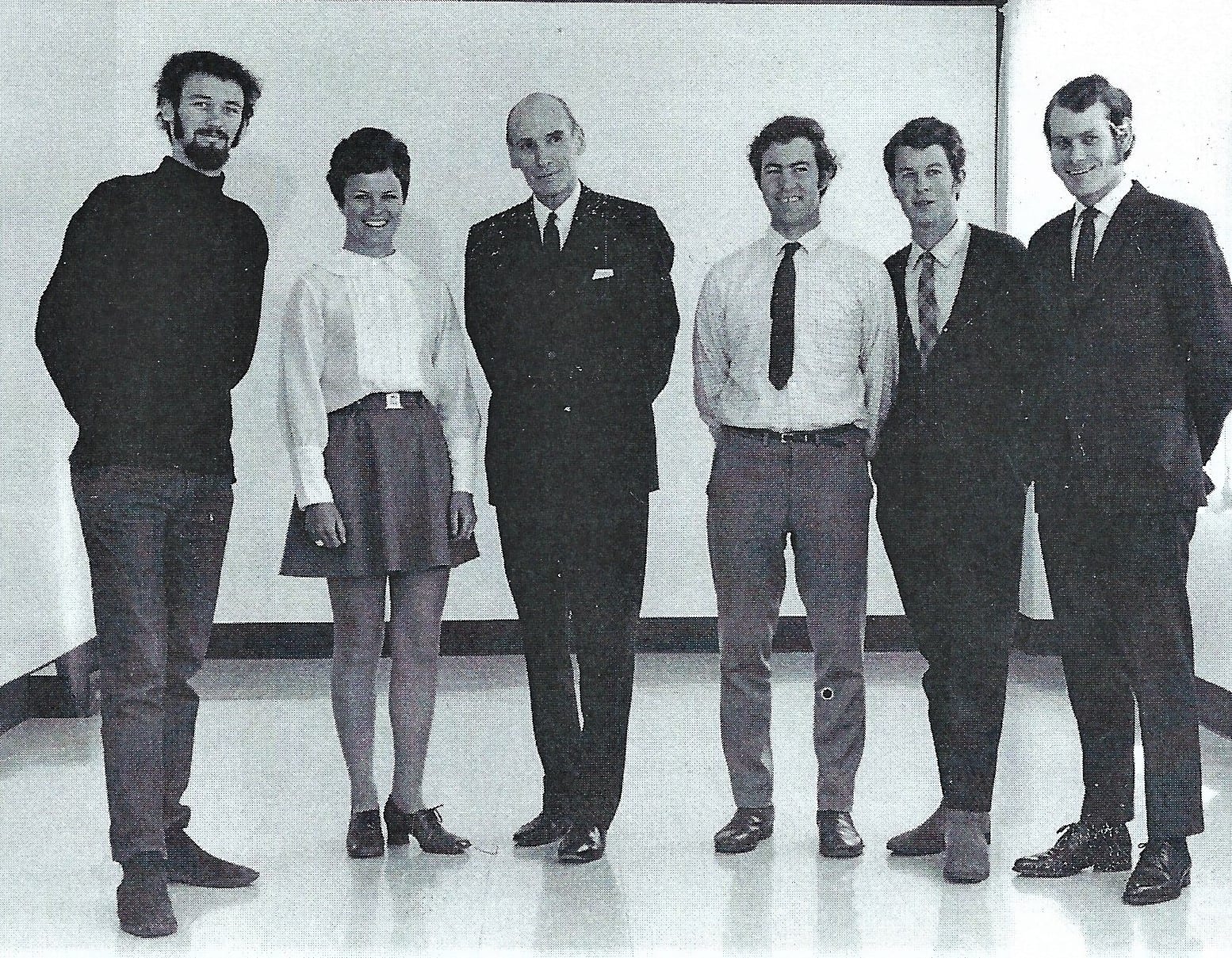

In 1964 Henley was granted leave of absence to help plan the Auckland Medical School, when it was approved by government after a lengthy campaign, and he played a central role in the deliberations of the Senate Medical Committee. In 1968 he became the inaugural president of the Auckland University Medical Students Association and spoke at their first dinner. In 2017 Peter Charlesworth, one of the original 1968 students, provided a compelling pen portrait of Henley.

Henley’s contribution to the new medical school was acknowledged in 1973 with the institution of the WE Henley Prize in Clinical Medicine, awarded each year to the MB ChB Part VI student who submits the best case history with associated commentary. He also had a lecture theatre named after him in 1974, when he was credited with having conducted much of the detailed planning for the school.

The frontispiece of many of Douglas Robb’s publications used the image of a sower of seeds.

John Scott on Douglas Robb

Sir John Scott (1931-2015) was professor of medicine at the University of Auckland from 1976 until 1996. Here he recalls being recruited in 1962 by Sir Douglas Robb to return to Auckland from England.

Vice-Chancellor Kenneth Maidment’s telegram to Douglas Robb, 25 November 1964.

Medical superintendent-in-chief Wilton (`Chook’) Henley (right) nonchalantly watches the Auckland Hospital 1870s main building being demolished in 1964, the same year in which he became involved in planning the Auckland Medical School.

Peter Charlesworth on Wilton Henley

Wilton Henley with members of the original AUMSA committee, 1968.