THE GRAFTON CAMPUS

This section traces the Grafton Campus from its origins as a missionary school in the 1840s to its development since 1968 as the home of the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences.The Site

In 1844 part of the area now bounded by Grafton Road, Park Road and Carlton Gore Road and occupied by the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences was set aside by government as a venue for a Wesleyan Missionary Society school. In the 1850s this was relocated to Three Kings and survives to this day as Wesley College, now situated just outside Pukekohe. After the 1850s transfer one of the Wesleyan staff, the Revd Henry Lawry, purchased part of the adjacent lands and built a homestead for his extended family. As Lawry wrote of the original 1840s grant, `The Governor has given us the most beautiful spot I have seen in this land.’

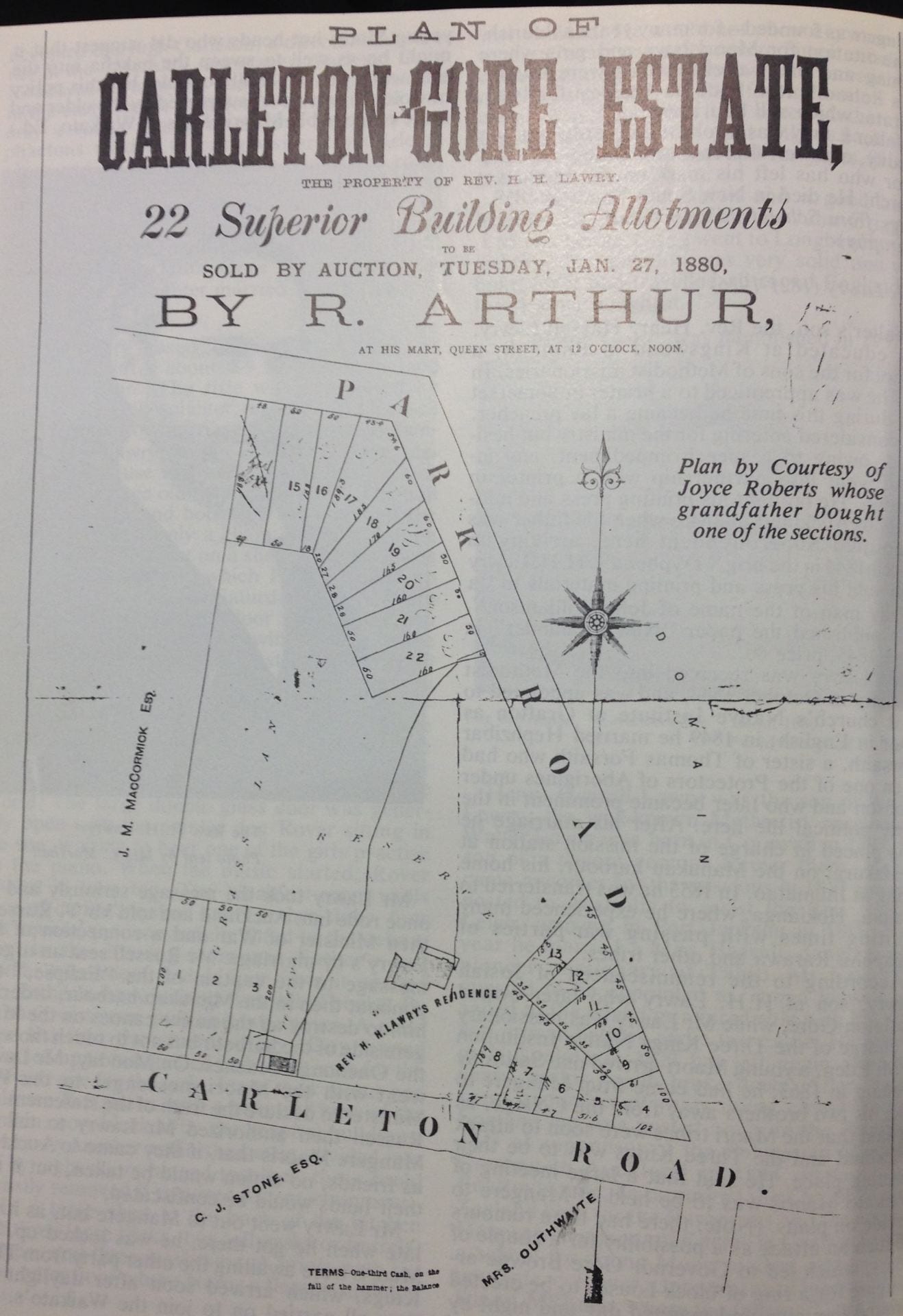

In 1880 Lawry broke up his estate, offering for sale 22 `splendid allotments’ for the erection of villa residences – many on the area now occupied by the Liggins Institute.

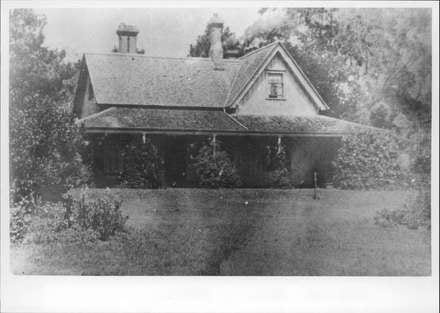

A decade later tragedy struck when Lawry’s own residence was razed to the ground, though they did manage to save the bulk of his precious library. Worse was to follow. On 29 October 1894 the Wairarapa was wrecked off Great Barrier Island with the loss of 121 lives, including Lawry’s daughter. Her brother, Thomas, who had graduated MB CM Edinburgh in 1883, the year in which the Auckland University College came into being, travelled north in search of news of his sister, contracted pleurisy and pneumonia which he was unable to shake off, and died in June 1895 aged 38.

The Revd Henry Lawry died in 1906 and over the next half century the house which he had rebuilt after the 1891 fire gradually fell into disrepair. It was demolished in the mid-1950s with the intention that it would be replaced with flats.

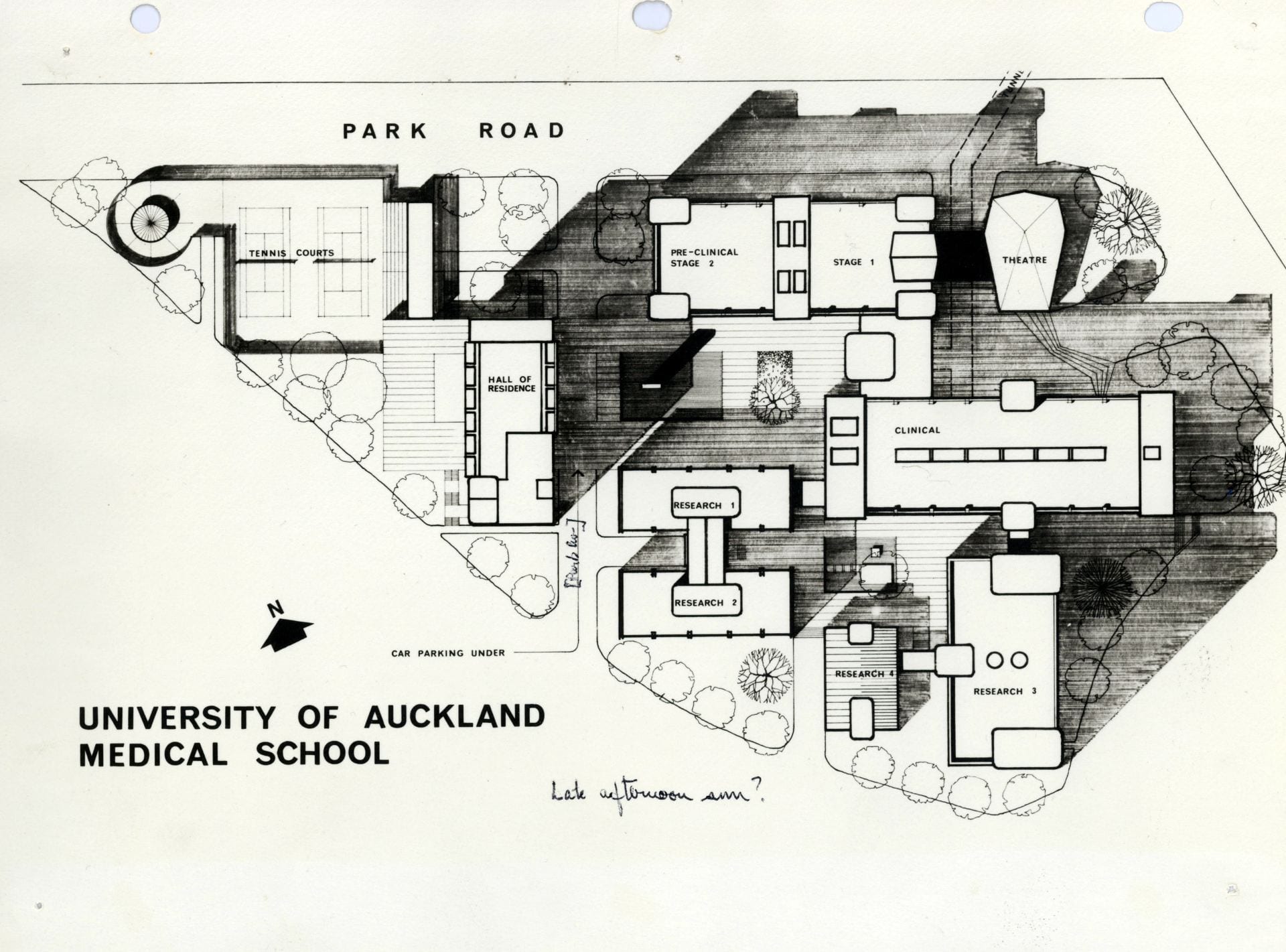

In the event, the land and buildings surrounding Lawry’s truncated estate were targeted as the site of the proposed medical school, though not without staunch resistance, primarily from the Newmarket Borough Council. In the end the parliamentarians and others agreed that Grafton was the only suitable site, with the proviso that the development should be vertical, not horizontal, given the land value and the demands for residential property.

Jack Sinclair on the Grafton Campus

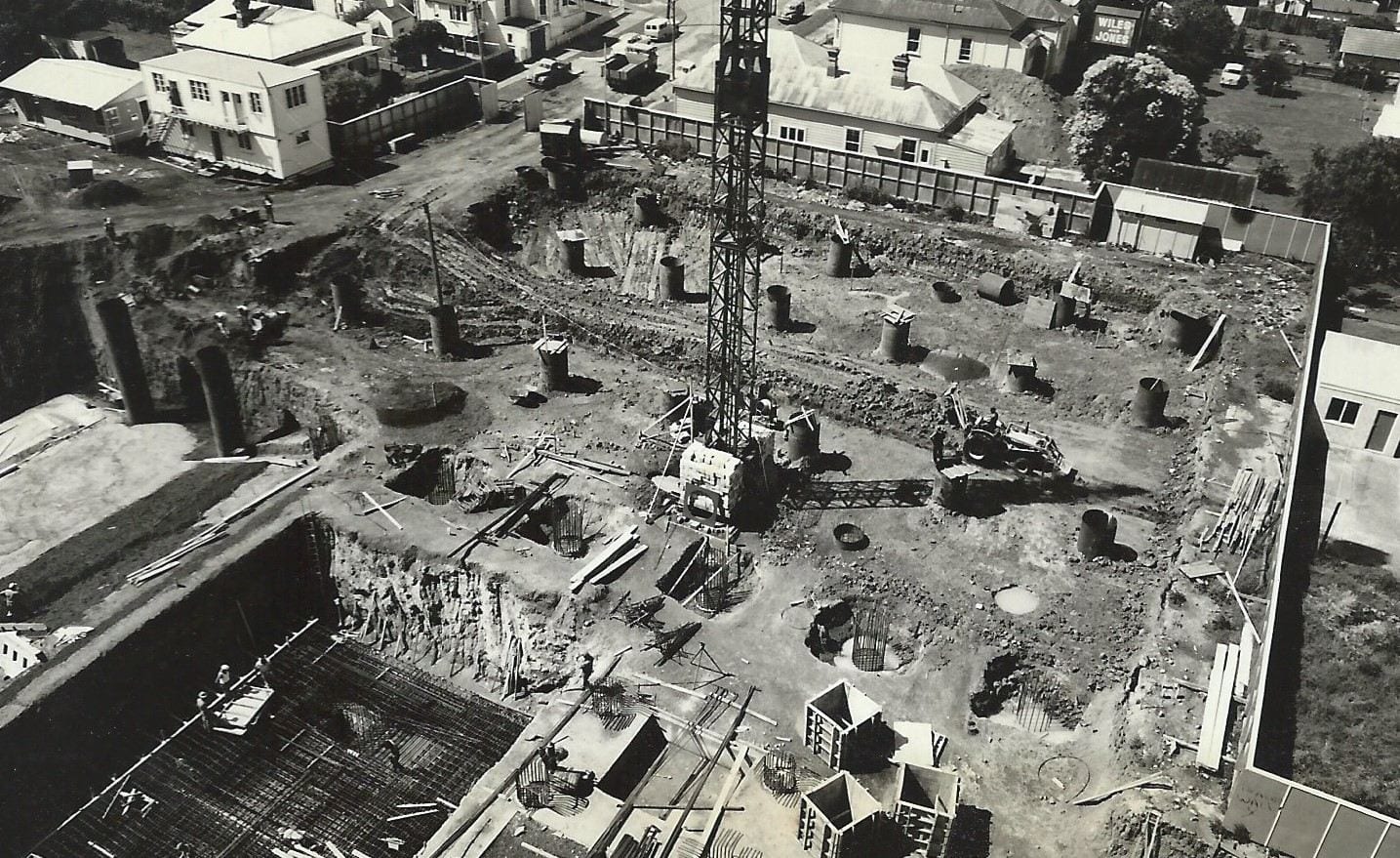

In August 1964, three months before the Auckland Medical School was given the official go-ahead, Education Minister Arthur Kinsella was asked in parliament when building might commence; he refused to hazard a guess. Two years later, Kinsella was still fighting a rearguard action, attempting to blame the University of Auckland for any delays while at the same time revealing that nothing could have been done until the appeals against the purchase of the site had been completed just weeks earlier.

In fact the chosen architects, Stephenson and Turner, had submitted plans in February 1966, along with a query about the long-term development of the site:

Question 1 – Can a building be designed economically to meet the immediate requirements of Schedule B and be readily expandable to take the full schedule as set out in Schedule A?

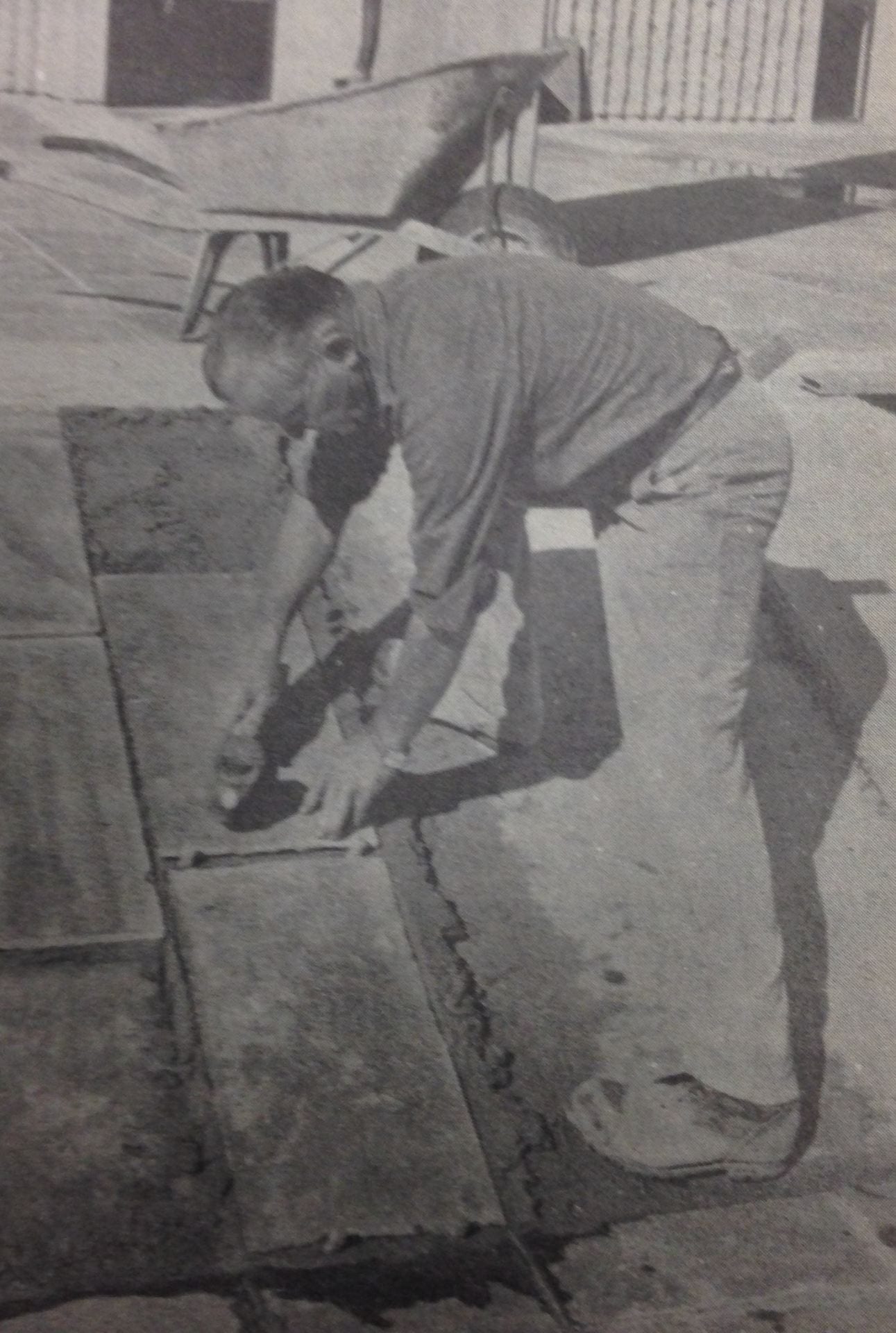

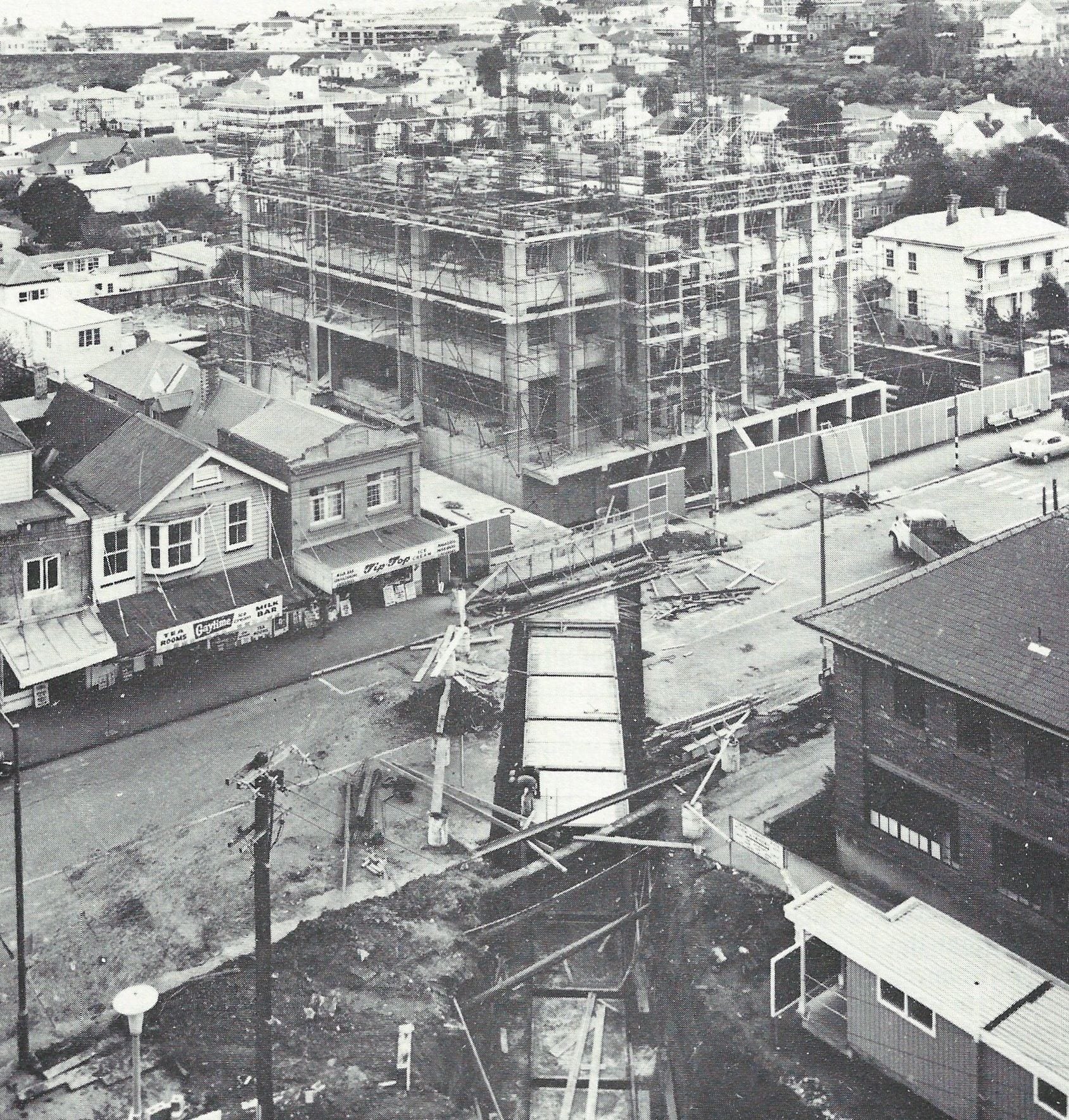

The design of the Auckland Medical School reflected the brutalist style of architecture, which generally utilised a fortress-like appearance with swathes of exposed concrete. Many years later John Lindsay, one of the original 1968 student intake, recalled his part in the realisation of the architects’ vision, while working as a builders’ labourer during the earliest stages of the construction.

John Lindsay on the Grafton Construction

Many of those who studied and worked at Grafton were not enamoured of the construction methods. Felicity Goodyear-Smith, who was a first year student in 1971 and was appointed to the Chair of General Practice in 2010, succinctly expressed her opinion of the building in 2017: `It wasn’t a very nice building. It always smelled of wet concrete, and it still does.’

The unyielding stone motif extended to the foyer and the link building, with the University News reporting in September 1973 that the greenish-grey quartzite used for the floor in the foyer had been sourced from Arctic Norway, and was cheaper than South Island stone.

Building continued for another five years, with Acting Dean Cam Maclaurin confirming that the opening of the pathology building in October 1978 meant that `the major programme of buildings was generally brought to completion’.

In 1974 John Carman, the inaugural Professor of Anatomy, had compared the dreams of Douglas Robb, Cecil Lewis and Wilton Henley (medical superintendent-in-chief of Auckland Hospital) for the Medical School with that of Jørn Utzon, the Danish architect who had designed the Sydney Opera House, completed in 1973.

Credit is also due to Carman himself, who was crucially involved with the conception and construction of the Grafton complex. As Carman’s obituary in the FMHS Dean’s Diary of 17 August 2012 noted:

His impact on the new medical school at Auckland extended beyond anatomy and in those early days he put his abiding interest in engineering and functional design to practical use, helping ensure that the architects for the original buildings on the Grafton site `got it right’.

The doubling of the Medical School intake in 1975 placed additional pressure on the main campus facilities which up until that time had accommodated physiology. A temporary solution was provided in the form of ex-US Army Quonset huts on the Grafton site as laboratories. These prefabricated corrugated steel buildings had been developed by the US Army in WWII, based on the British WW1 Nissen huts. As Graham White, who taught Physico Chemistry for more than 30 years, recalled, `they were pretty old’.

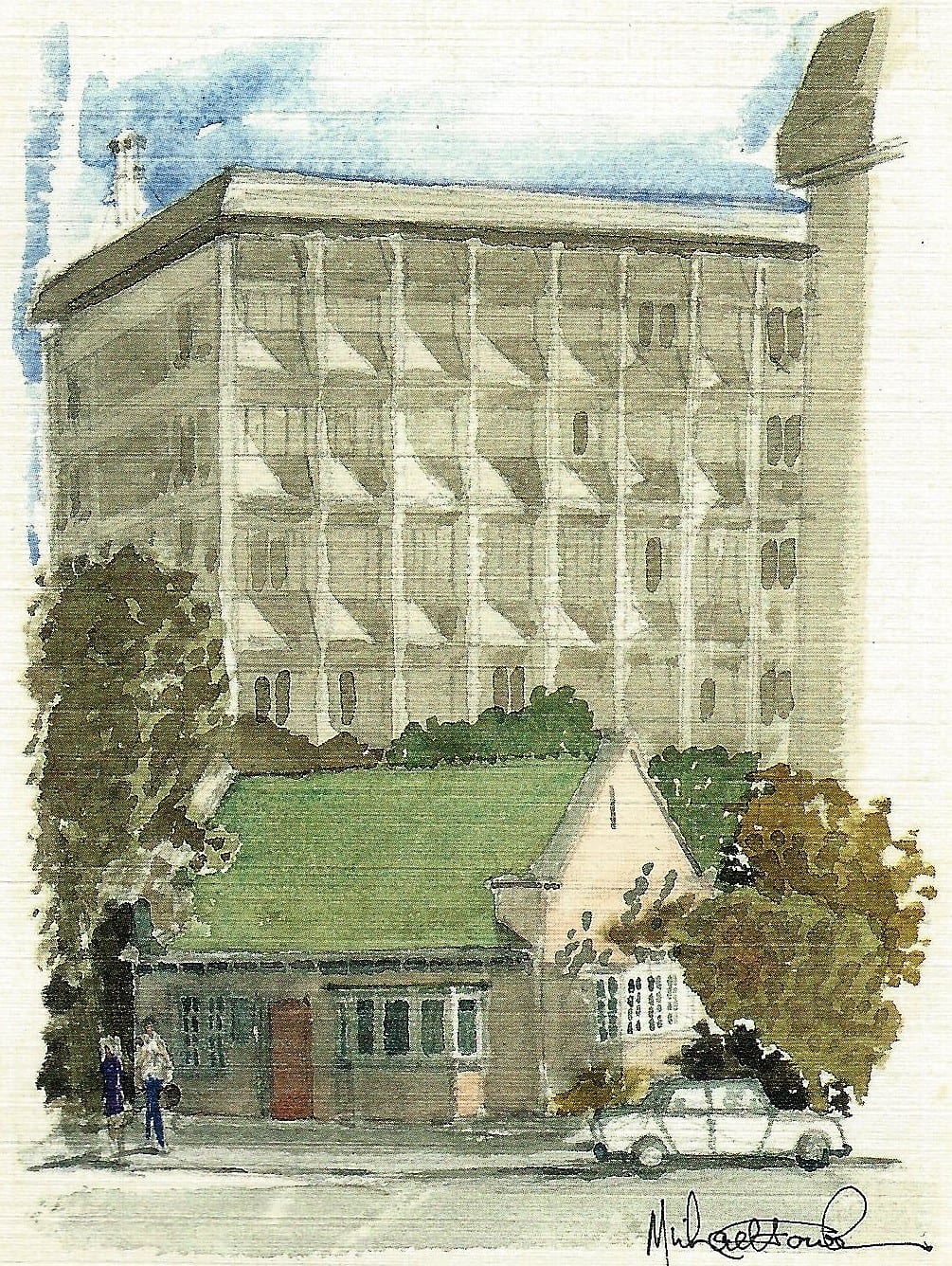

The Pink Cottage

One of the features of the FMHS site during its first four decades was the survival in the midst of the new buildings of the Pink Cottage, which had initially housed the Dean’s office during construction of the Pre-Clinical Building in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

In 1972, at Cecil Lewis’s instigation, the Pink Cottage became home to the new Department of Community Health, prompting the Auckland Star to comment that a renovated cottage with stable doors provided the `right environment for a return to simple values that must underline human progress’. As Rex Hunton, one of the pioneers in Community Health, later recalled, the building was `approachable and less intimidating than the Medical School’. The counselling service provided by Hunton and his colleagues in this public health clinic was one of the driving forces behind the contentious Auckland Medical Aid Trust, set up in 1977 as an abortion clinic.

The building was repainted in 1996 in what the University News described as a `more dignified white’ and taken over by Student Affairs which provided medical services, counselling and chaplaincy facilities, and careers and financial advice.

In 2008 the Pink Cottage was demolished to enable Auckland Council to widen Grafton Road, as part of its new central transit corridor. This initiative attracted little official comment, with the University’s annual report for 2008 noting, in its Statement of Resources, a reduction in gross floor area which included `Demolition of Grafton Campus The Pink Cottage’.

For some, the loss was more poignant. In a 2017 interview Professor Felicity Goodyear-Smith from the Department of General Practice and Primary Healthcare, wistfully commented that: `Now there’s just grass there, but for years there was this pink cottage.’ More touching still, Professor Louise Nicholson, who had maintained correspondence with former Dean Cecil Lewis, recalled:

I was a bit sad when the Pink Cottage disappeared because – it had a stable door on the street – and he said that he would have liked to have spent his last few years leaning on the stable door and watching these changes as they took place.

This watercolour of the Pink Cottage, painted by Sir Michael Fowler (b. 1929), a well-known architect and Mayor of Wellington 1974-83, was reproduced on the front cover of the School of Medicine’s 25th anniversary publication in 1993.

Royal Visits, 1970 and 2002

During its first half century the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences had two visits by the reigning monarch, Queen Elizabeth II. The first of these was on 24 March 1970 to mark the official opening of the Auckland Medical School. It occurred during the Queen’s visit to celebrate the bicentenary of Cook’s voyages to Australia and New Zealand. Two days after her visit to the Medical School the Queen attended a state farewell dinner in Auckland.

The visit to the Grafton campus was decidedly informal, with security which appears to have been very relaxed. One of the highlights of the visit was a tour round one of the teaching laboratories, where students from the initial 1968 intake had obviously been briefed to act as normal and not to look up as the Queen entered. Denys Boshier, then a member of staff in the Department of Anatomy, recalled what happened during her tour:

And she of course walked around the laboratory and spoke to a number of people. One thing I remember particularly well: there was a student from Rotorua whose name was Beverley Luscombe, and the Queen had a look through her microscope. The topic that we were doing for that particular day was the human ovary. Of course, queens never look at ovaries. There was a lovely picture in the Herald a day or two afterwards with the caption: `Queen looks at blood smear in University class.’ I really don’t know what the Queen might have thought when she found she was looking at a human ovary!

During her 50th jubilee tour of New Zealand in 2002 the Queen paid a return visit to the FMHS to open the Liggins institute on 26 February 2002. There she was shown a number of research projects, including Jane Harding’s work on small babies, monitoring for brain damage in babies’ brains, and the cooling cap developed by Peter Gluckman and Tania Gunn.

Redeveloping the Grafton Campus 2005-2012

In 1977 James Bartley, who would graduate in 1981, expressed concerns about the fragmented nature of the Medical School in a letter to the medical student magazine, Quack:

It is a sad fact that due to the nature of our course, we are not united as a Medical School. Some of us are down at University, some at the Medical Faculty and some in the hospitals.

It would be more than a decade before the pre-clinical departments were relocated from main campus to Grafton. Not everyone was happy with this change, with comments in the University News that the downside was the loss of opportunity to take extra papers outside of the medical curriculum.

Another 15 years elapsed before there were any major developments to the Grafton campus. The first of these was the Grafton Information Commons, officially opened on 17 March 2004 by Dr John Mayhew, a 1979 Auckland graduate and All Black doctor 1988-2003. As the AUMSA president remarked at the time:

There aren’t many positive things you could say about the former facilities, except we had a great pool table. The old computers must have been powered along by coal, they were that slow.

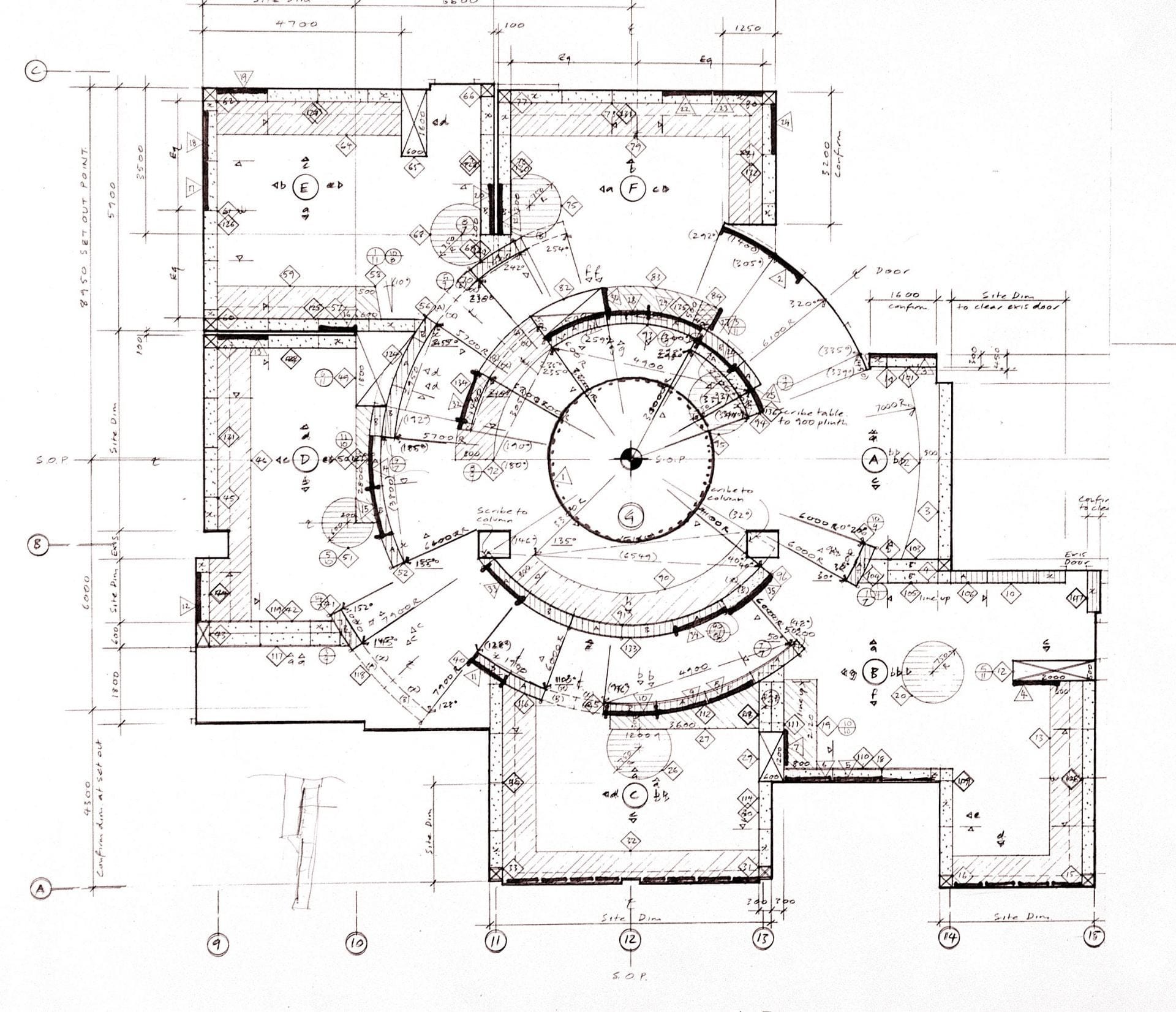

The following year saw the opening of the state-of-the-art Medical Sciences Learning Centre for undergraduate, graduate and postgraduate education in anatomy, radiology and pathology. Instigated by Professor Peter Browett and Associate Professor Mervyn Merrilees and overseen by Head of Department Associate Professor Cynthia Jensen, this was partly funded by a $500,000 gift from the Auckland Medical Research Foundation which was celebrating its 50th anniversary of funding medical research in the Auckland region. Designed by local architect Rick Pearson, it was opened by Prime Minister Helen Clark on 2 December 2005 and won a number of architectural awards.

Cynthia Jensen on the Grafton Redevelopment

To this end Martin visited Australia in 2007 to benchmark the Auckland plans against the Australian biomedical institutions. The outcome was a redevelopment proposal incorporating the entire site and not just the existing buildings. The University Council approved the $240 million Grafton Campus Redevelopment Programme in February 2009, with Martin commenting in his Dean’s Diary that `to some extent, the easy bit is now done and the hard work begins in planning what will be a very complex series of staged projects.’

John Fraser on Grafton Refurbishment

The new Grafton campus was opened by Prime Minister John Key in July 2012. Officially designated building 505, the new premises were colloquially referred to as the Boyle Building because they straddled Park Road and Boyle Crescent, occupying a space formerly the site of three villas and a car park.

The architects of the transformation were JASMAX of Auckland and Daryl Jackson Architects PTY of Melbourne, whose work was honoured by the New Zealand Institute of Architects, which praised the successful integration with the 1970s brutalist buildings, to ‘revivify an important academic institution’.

The refurbishment also saw a major uplift for the old main entrance, summed up by Stuart Glasson, now (2018) the Director of Faculty Operations:

The old entrance was not a terribly welcoming entrance. It was basically an entrance into a lift lobby and some corridors, whereas now we have this – you know – atrium entrance with a nice cafeteria and lecture theatres, one floor up information commons, Philson Library. And all that space is effectively public space, it’s an extension of the footpath during normal working hours, people can walk in. It’s just a nicer environment for a lot of those reasons. Of course it looks modern. But back before this development it didn’t have that atmosphere.

The reunions of successive groups of alumni provided valuable feedback on the changes to the Grafton campus.

In 2014 Dean John Fraser reported that the class groups were `almost universally entranced’ by the Medical Sciences Learning Centre. The groups were impressed by a number of other changes but `delighted’ to find very little alteration to the Robb Lecture Theatre. Two years later many of the graduates of 1976, 1981, 1986, 1991, 1996, 2001 and 2006 `were astonished at how different the Grafton Faculty looks from the old grey “fortress” of the past’.

The opening of the Medical Science Learning Centre, 2 December 2005, with (l to r): Bruce Cole, Associate Professor Cynthia Jensen, Helen Clark, Te Paea Sophie Muru, Dr Paparaangi Reid (tumuaki), Professor Peter Browett.