FOUNDATION STAFF

This section tells the story of the professors and other academic staff appointed from 1967-74.In 1967, with the Dean now firmly established in post and construction of the Medical School buildings under way, it was time to start appointing the foundation staff. The first positions to be filled were senior lectureships in physico-chemistry and biology, to meet the immediate needs of the first-year pre-clinical students who would arrive in February 1968. These were followed over the next four years by the foundation chairs in biochemistry, anatomy, physiology, medicine, pathology, surgery, paediatrics, endocrinology, psychiatry, and community health, adding to the existing postgraduate chair of obstetrics occupied by Dennis Bonham since 1964. As Jack Sinclair, foundation professor of physiology, remarked many years later:

The Dean of Law couldn’t believe that the Medical School couldn’t start with ten professors, whereas the Law School had one or two.

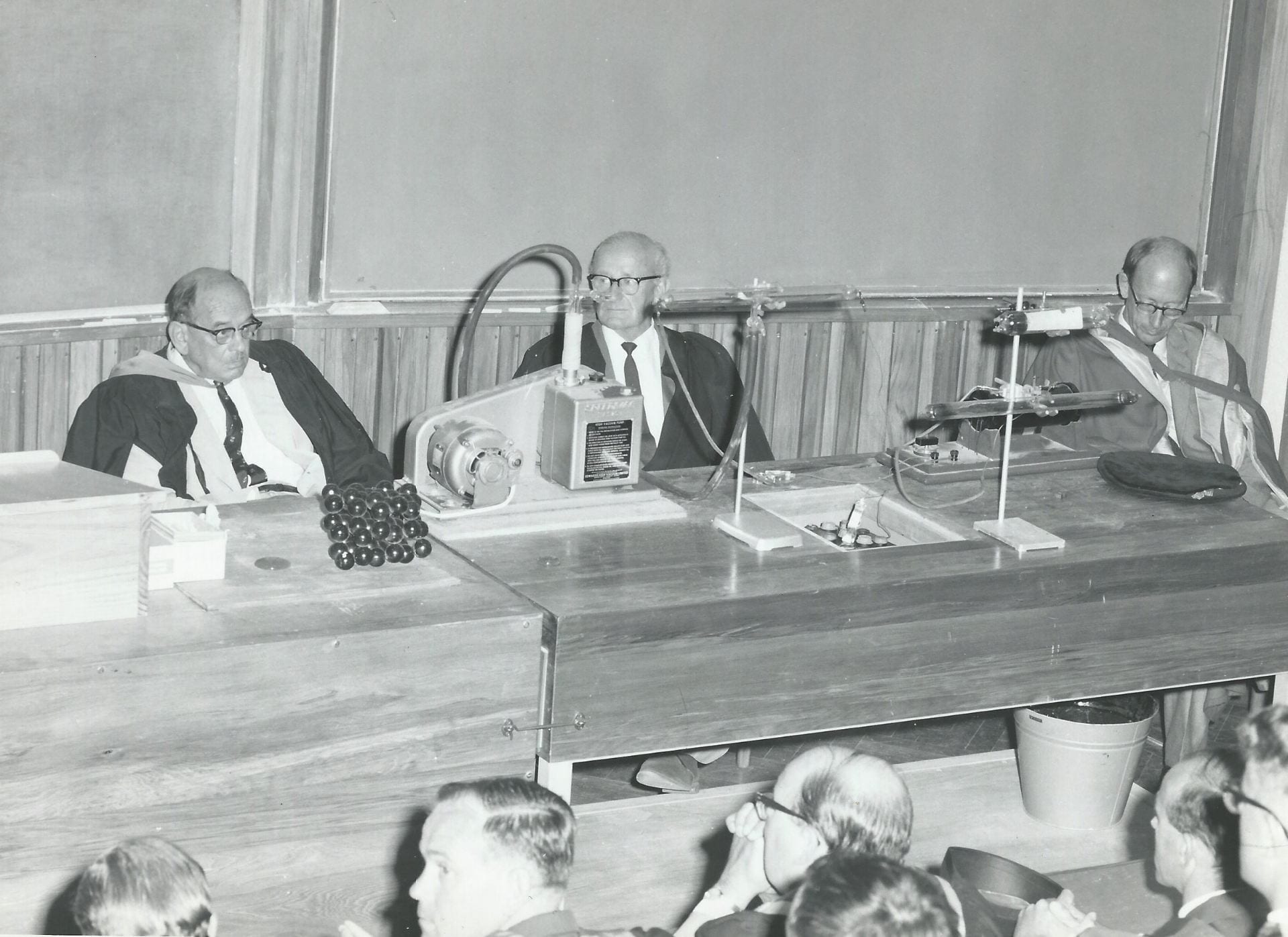

Setting up a medical school was a daunting undertaking. The University Registrar James Kirkness was closely involved in the process, including attending the inaugural lecture in February 1968. When he retired in 1971 the University Bursar Kathleen Alison noted the multiplicity of tasks he had confronted during his 23 years in office, including `most bewildering, most complicated, most disturbing, and if our appendixes are to be safe in the future, most stimulating of all, the Medical School’.

A majority of the new appointees were Otago graduates, almost all of whom had gained postgraduate experience in the UK or the USA. Some had been mentored or targeted by Sir Douglas Robb, then the University Vice-Chancellor, who maintained a keen interest until his death in 1974. Professor of Psychiatry John Werry remembered Robb’s interest fondly in a 2017 interview.

According to Professor Richard Faull, who completed his Auckland PhD in 1975, these early appointees enjoyed considerable power of primacy:

The foundation professors set up sort of fiefdoms within the school. I say that in the nicest possible way because they were absolutely passionate about their discipline. And when you had Faculty meetings, the foundation professors sort of ran the faculty meeting. The Dean ran them, but they would get up and defend their territory. They had very clear, pure idealistic notions of exactly where their discipline should be. They really defended all the things which were important to creating Anatomy, Physiology, Pharmacology, Pathology and all the rest of it. So they ruled the roost.

Bob Elliott, in a 2017 interview, outlined the pecking order at the early Faculty meetings.

Writing in the New Zealand Medical Journal in December 1968 Dean Cecil Lewis summed up his foundation staff as `the nucleus of a very fine team’. Time would fully justify the claim.

Registrar James Kirkness at the inaugural lecture, flanked by Douglas Robb (left) and Dean of Science John Morton. Seated in the front row are (from left) Derek North, Dennis Bonham and Kaye Ibbertson.

John Werry on Douglas Robb

Bob Elliott on heads' meetings

Dennis Geoffrey Bonham (1924-2005): Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1964-89

When Harvey Carey resigned the postgraduate chair of obstetrics and gynaecology in 1962, his replacement was Dennis Bonham, a Cambridge medical graduate who had been a lecturer in Professor William Nixon’s Obstetric Unit at University College Hospital, London since 1960. As Nixon’s biographer commented:

It was Nixon’s ambition that all his assistants should fly the nest as professors and consultants in other parts of the UK and the world. They would be missionaries of his philosophy and few of them did not so succeed . . . . Several record being called to his office to be told that a professorship had been arranged for them in some other part of the world.

Bonham arrived in Auckland in December 1963 and was immediately shoulder-tapped by Sir Douglas Robb and others to head `The Senate Advisory Committee of the University of Auckland on the academic implications of a second medical school’, which held its first meeting on 9 April 1964. He undertook this onerous task until the arrival of Dean Cecil Lewis in 1966. Jack Sinclair, a colleague for almost a quarter of a century, regarded Bonham as `a very energetic and relatively far-sighted chairman of that committee’. Jack’s brother, Sir Keith, described Bonham in his 1983 history of the University of Auckland as `a human dynamo and a great success’, responsible for ‘an excellent centre of research’.

Bonham’s influence continued after Lewis’s arrival, with Bob Elliott, inaugural Professor of Paediatrics, stating in 2017 that `invariably Dennis Bonham would be sitting on the right hand side of Cecil Lewis’ at the heads of department meetings.

In 1963 Bonham and his colleague Neville Butler published the first report of the British Perinatal Mortality Survey established in 1958. He extended this interest to New Zealand, masterminding the 1968 Maternal Mortality Research Act, becoming founding president of the New Zealand Perinatal Society in 1980, and acting as an adviser to WHO.

In his 2005 obituary Professor Peter Stone recalled that Bonham’s inaugural lecture had described his chair as having four legs – teaching, clinical work, research, and administration – and that he had excelled in all four roles. One of his particular interests was expanding the number of women practising obstetrics and gynaecology. After Hilary Liddell and Lynda Batcheler graduated from Auckland in the late 1970s Bonham arranged a job-sharing post so the two women could combine careers with raising a young family. He did much the same in the 1980s for Lesley McCowan, who later played a crucial role in the foundation of the New Zealand Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee, and became head of the University Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in 2009.

Bonham’s drive to ease the path for female doctors was supported by his wife Nancie, who was part of a group of women who set up the University of Auckland crèche in 1968 to enable new mothers to attend lectures, and was also a prime mover in the University Wives’ Association established around the same time.

Dennis Bonham was combative and single-minded in his approach, antagonising many in the medical community and beyond, as Sir John Scott observed in an interview three years after Bonham’s death.

John Scott on Dennis Bonham

Despite these reservations, Bonham’s 21 years as head of school were commemorated in 1985 with a dinner and the presentation of an illuminated address. His later years, however, were overshadowed by the controversy surrounding the so-called `Unfortunate Experiment’ and the subsequent Cartwright Inquiry. As Scott also commented:

Many academics of my generation regard his life as one of achievement tinged with sorrow and regret.

Inaugural 1968 student Sue Thomas standing behind Professor Bonham in this 1971 photograph is living proof of Bonham’s support for female students. From 2013-17 Dr Sue Fleming, as she became after her marriage, was Director of Women’s Health for the Auckland District Health Board.

Dennis Bonham’s Auckland career was bookended by seeing his sons graduate in medicine from the School he had helped to shape. Richard, pictured here as a 5th year student in 1972, was one of the initial 1968 intake of medical students. His second son, Martin, qualified in 1989, the year in which his father retired.

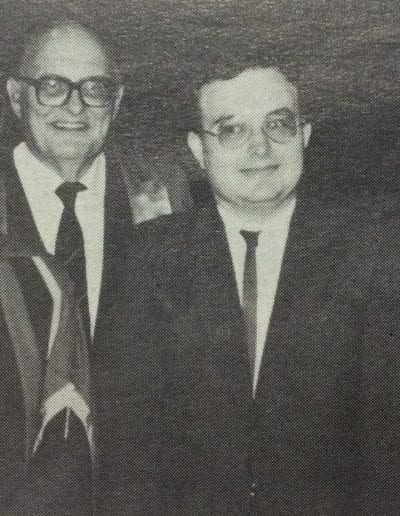

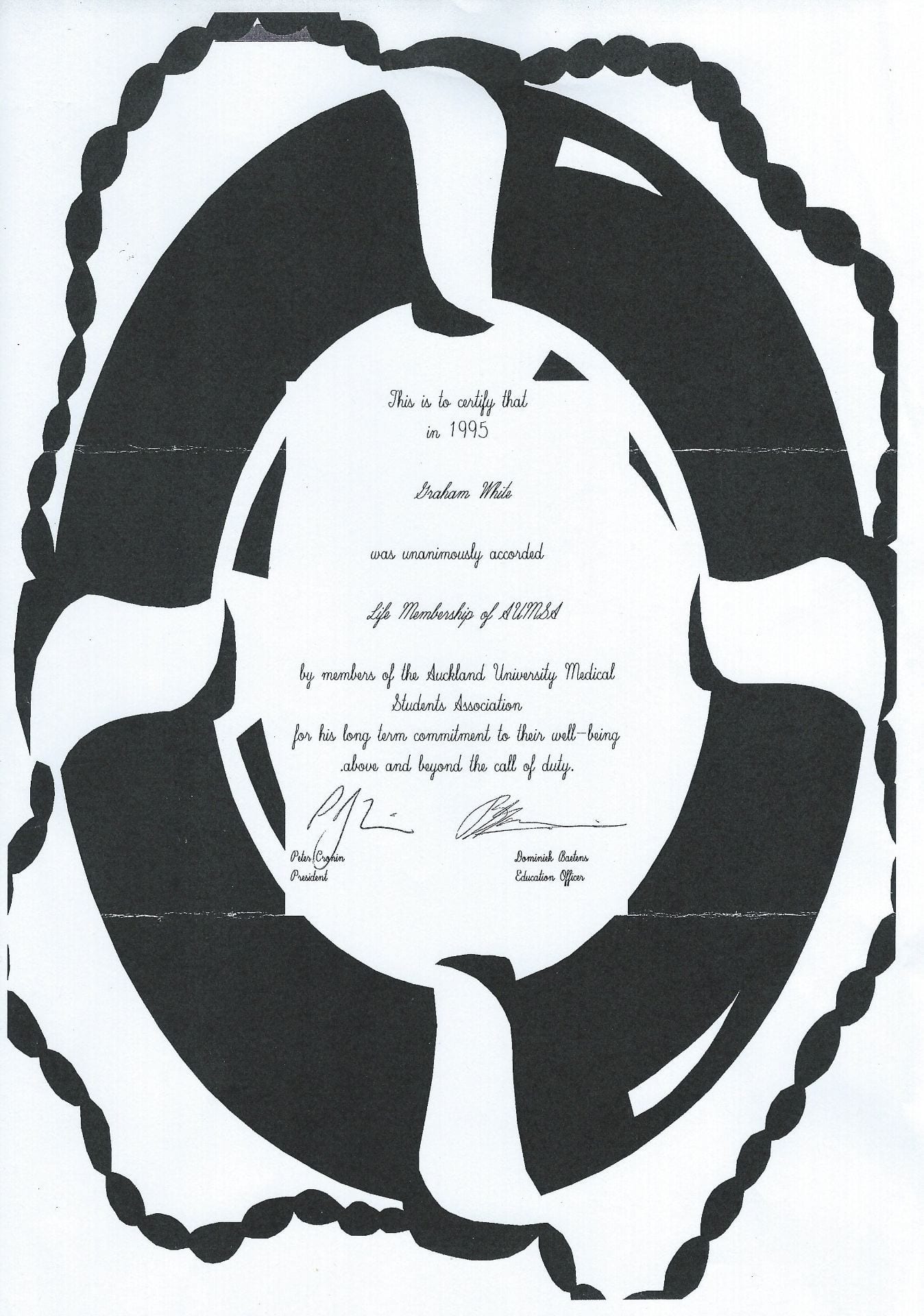

Graham White (1937-): Physico-Chemistry 1967-99

The first appointee to the Auckland Medical School lecturing staff on 11 July 1967 proved to be an inspired choice. Graham White, an Auckland chemistry graduate, had taught on the medical intermediate course for prospective entrants to the Otago Medical School from 1963 and jumped at the chance to become part of the Auckland venture. As he recalled in 2017, the job description for the senior lectureship in physico-chemistry, that `the successful applicant will be expected to make a substantial contribution to the Bachelor of Science course in Human Biology and to take part in its detailed organisation’, appealed because `I loved organising things and doing timetables and choosing students’.

White was soon recognised as someone who went the extra mile, with Vice-Chancellor Colin Maiden commenting in 2017 that he:

was absolutely dedicated to the School and the students and was absolutely marvellous in his contribution to that School through the years.

Other staff members were equally fulsome in their praise, recognising White’s influence on the shaping of the curriculum for the pre-clinical years, and his skill in helping students to transition from school to university, in some instances from a non-scientific background to the demands of the medical world. Equally important was his pastoral care, visiting schools and families at home to ensure a smooth transition if at all possible. If Douglas Robb and Cecil Lewis were respectively the father and the midwife of the new School, White was, in the words of Graham Vaughan, the School’s first psychology lecturer, the mother duck.

Vaughan’s view was endorsed in 2017 by John Werry, the inaugural Professor of Psychiatry, who described White as `the students’ friend and a conduit for students’ opinions, and not so much about academic matters but about the wellbeing of students’.

That assessment was shared by the students themselves. Innes Asher, who topped the first student group in the final exams, regarded him as a `very very fine teacher’, as well as a `somewhat self-appointed’ mentor whose crucial role was not fully acknowledged over the years. As one of the youngest members of staff White had a particular rapport with those admitted straight from school but he also crafted the course to stimulate the more mature entrants who formed about 20 per cent of the intake in the first year as John Faris, the son and grandson of doctors, recalled:

John Faris on Graham White

This influence extended well beyond the classroom. Almost half a century after the event, several of the first intake recalled a trip to the Waiwera Hot Pools organised by White on 20 June 1973. Afterwards White invited all the students back to his home for supper and coffee, even though he had just moved house and had 2 small children.

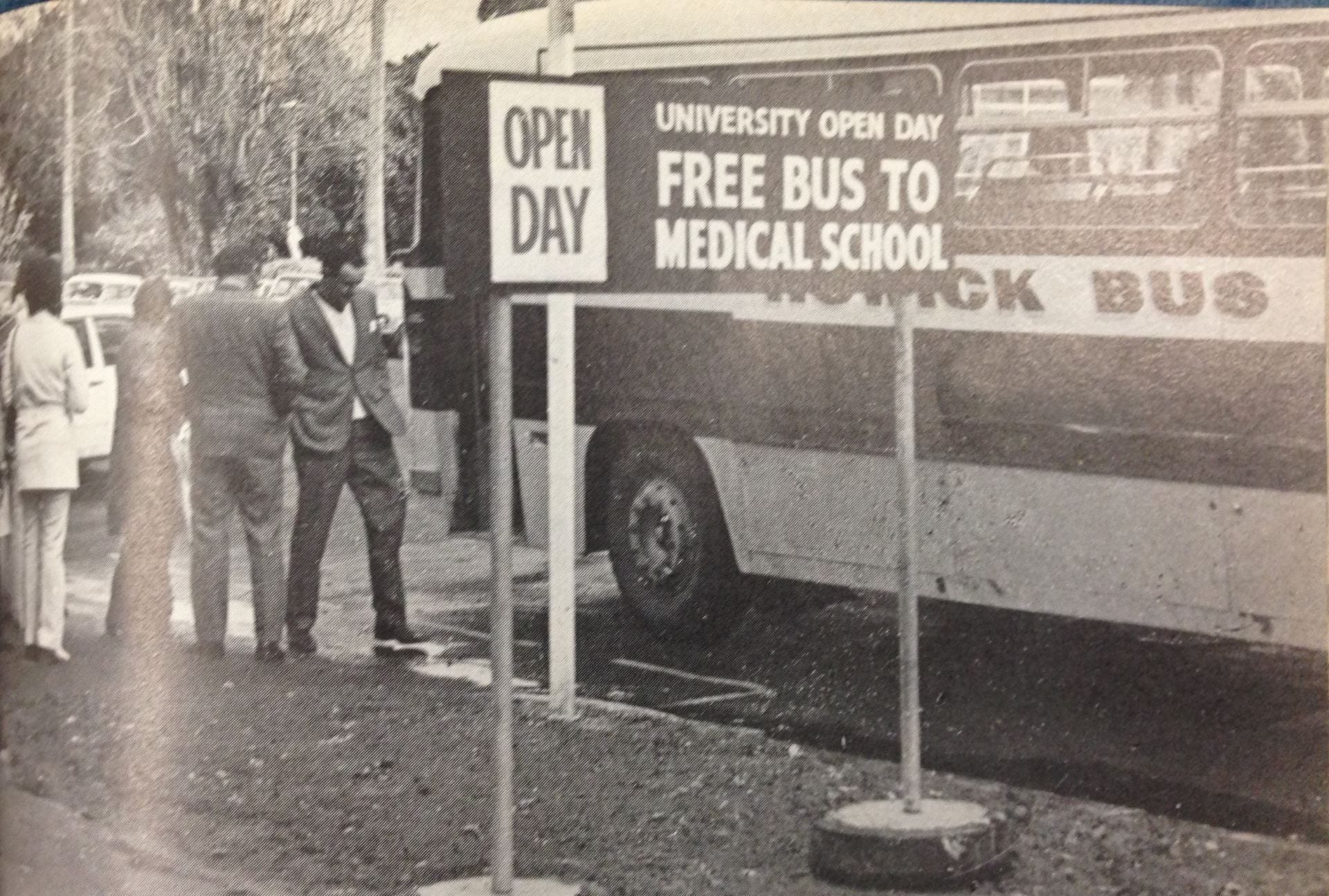

White also worked hard to maintain contact with the university main campus, to try and minimise the divide between Symonds Street and Grafton. In June 1972 he was chairman of the first University of Auckland Open Day Committee.

When Graham White retired in 1999 Dean Peter Gluckman hosted a cocktail party to mark his three decades on the academic staff. Those contacts have continued, with Graham explaining in 2017 what he had taken from his career:

I always felt a bit sorry for the clinical staff because they were often called away by crises in the ward. Also they didn’t have that same contact with the whole class that I had in Year I, or that others in preclinical had, because they were often dealing just with subgroups, small groups of students on the ward. Hence when there were reunions there were virtually no clinical staff rolled up because they didn’t know the whole class, they knew some of the class. So I felt it was quite a privilege to have known the students so well and so many of them – over 3000 – over about 30 years or so that I was in the School. And I didn’t get bored by it! Because every year there was a fresh bunch.

Graham Vaughan on Graham White

George Mills: Biochemistry 1967-72

The first of the new professors was GT Mills, who was appointed to the chair of biochemistry on 5 December 1967. Mills had trained under HJ Channon in Liverpool in the early 1940s, courtesy of a Unilever fellowship, which he relinquished in 1941 to work for the Ministry of Food during the war years. He later went to America and was recruited from there for the Auckland post. Although he and anatomy professor John Carman were the only foundation professors with experience in teaching medical students, according to Jack Sinclair, his tenure was a short and not very happy one.

Within a few years the department was in considerable disarray. Mills departed and in 1972 physiology professor Jack Sinclair was roped in as interim HOD, a role he undertook until the arrival of Alistair Renwick in 1974.

John Burd Carman (1932-2012): Anatomy 1967-97

John Carman was appointed foundation Professor of Anatomy in December 1967 at the early age of 35 years, having completed his medical training at Otago in 1957, followed by an Oxford DPhil in 1961. His interest in the subject was sparked as a primary school pupil, when he chose a book on anatomy as his prize for becoming primary school dux in Johnsonville.

Carman was totally dedicated to his work, something recognised by the medical student magazine Quack in 1978 when it reported that after 10 years in post the professor was heading off on long leave since `he at last has a big enough staff to take a pause’. A former protégé and colleague, Sir Richard Faull, has commented on Carman’s contribution to the Auckland Medical School and his determination to see Auckland prosper.

From the outset students recognised Carman’s dedication to his subject although John Faris, one of the initial 1968 intake, queried the emphasis placed on anatomy in a 2017 interview:

In the pre-clinical years you couldn’t avoid JB Carman. Anatomy was the be-all and the end-all of a medical student’s education, without question. And I look at medical education today and what he thought. He thought you had to learn Anatomy for the sake of learning Anatomy, not for the sake of being a good doctor.

At the time, however, Steve Culpan, another of the 1968 students, praised Carman’s approach in his student diary:

Professor Carman is unsettling. He is constantly asking questions, which the students are actually required to answer, needing thought and concentration. This is good.

Students were also somewhat in awe of Carman’s artistic skills and his ability to conjure up three-dimensional drawings on the blackboard while he lectured. As Peter Charlesworth, also from the class of 1968, perceptively remarked, `nowadays it would be unheard of and some kind of Powerpoint would be flourished’.

A youthful Professor John Carman (centre) with Anatomy Department staff and students, 1976.

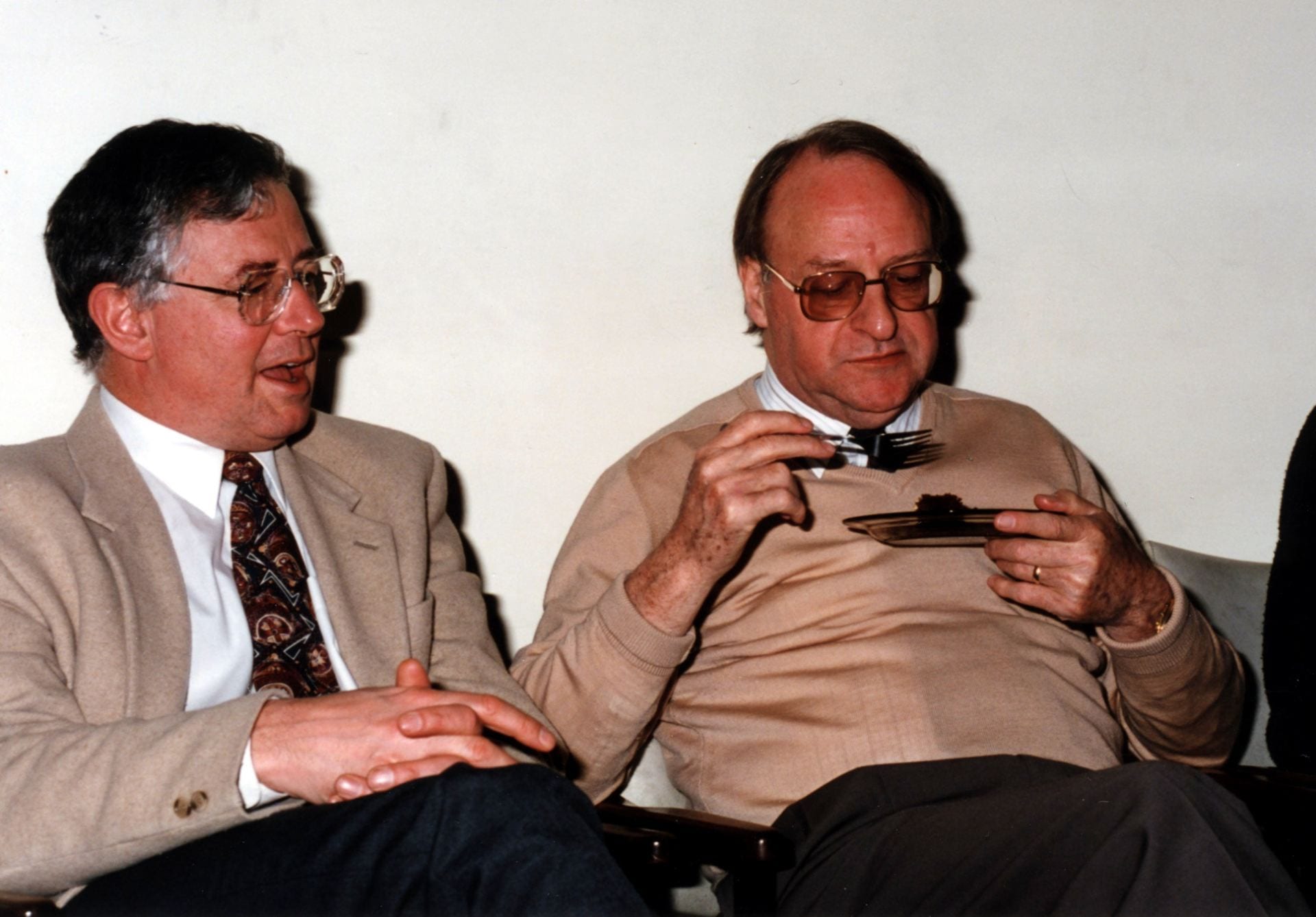

John Carman and Richard Faull, 1993.

Richard Faull on John Carman

John Desmond `Jack’ Sinclair (1927-2018): Physiology 1968-93

After graduating from Otago in 1950 Jack Sinclair began his postgraduate studies at Green Lane Hospital, encouraged by Douglas Robb. His interest in physiology stemmed from his time as an elite athlete who had competed as a miler at the 1950 Empire Games. As John Werry recalled in 2018:

At a university athletics meeting. Jack strode away from the field but it was the sheer grace of his running style that left me open-mouthed in admiration.

In the late 1950s Sinclair studied in London and at the Mayo Clinic in America under Earl Wood, who helped invent the G-suit in the 1940s to prevent pilots blacking out during flight. He returned to Green Lane in 1960 and renewed his links with the Medical Research Council, acting as its Scientific Secretary from 1966 until his appointment to the chair of physiology.

From 1964 Sinclair was a member of the University of Auckland Medical Advisory Committee. His interest in medical education first came to light in a 1963 contribution to the New Zealand Medical Journal on the merits of a BSc in Human Biology, an idea taken up enthusiastically by scientists and `Medicos’ alike, as Douglas Robb wrote to expatriate New Zealand botanist Lucy Cranwell in 1964.

In late 1967 Sinclair was offered the foundation chair of physiology at Auckland, an offer which he pondered for about three months before his appointment on 23 February 1968. Interviewed in 2008, Sinclair revisited what persuaded him to accept:

It was just an opportunity that was so unique, and it was only Douglas Kennedy of all the people I asked – and I asked a lot of people about it – and only Douglas Kennedy the Director General said, `I thought you were going to succeed me as Director General of Health,’ but he said `you don’t get an opportunity like that again in your life. You have to take it.’ Everybody else advised me exactly in their interests. I’d been on the Auckland University’s committee, so I’d been involved in all the discussions about the school and it was obviously going to be exciting.

Despite his department remaining on the main campus until the late 1970s, Sinclair was actively involved along with Dean Cecil Lewis, John Carman (Anatomy) and Peter Herdson (Pathology) in masterminding the structure of the original medical course. Former colleague John Werry described him as `sort of like the sage’ while psychologist Graham Vaughan and others sometimes referred to him as the `mini-dean’ because of his ability to convince Cecil Lewis to follow his suggestions.

Jack Sinclair retired in 1993 with the status of Emeritus Professor but continued to teach for another four years. Reflecting on his career in 2014 Sinclair summed it up in the following words:

It was enormously interesting, challenging. Yes, yes. Oh, I wouldn’t swap a day.

John Faris on Jack Sinclair

Jack Sinclair looking suitably sombre in academic dress.

As a former Empire Games runner, it was fitting that Jack Sinclair should have been a member of Auckland Joggers, founded in February 1962 as the world’s first jogging club. Here he is pictured with Colin Kay, Mayor of Auckland 1980-3, a triple jumper and Sinclair’s teammate at the 1950 Empire Games in Auckland.

John Derek Kingsley North (1927-2016): Medicine 1968-92

As foundation Professor of Medicine, Derek North was instrumental in developing a research culture in Auckland, embracing both clinical and biomedical elements. By the time he relinquished the headship of the department in 1979 it had expanded from one professor in 1968 to 3 professors, 3 associate professors, 4 senior lecturers, 2 named research fellows, and 44 clinical teachers.

The high standards set by North were daunting for some students and staff but did provide a solid academic grounding. He mentored young doctors to train in specialist fields at home or abroad and worked assiduously to create posts for them when it was time for them to return to Auckland.

Derek North (2nd from left), in his time as Dean, overseeing the planting of a ginkco bilabo or maidenhair tree, claims for the medicinal properties of which have not been borne out by a number of controlled trials. North was flanked by members of his core management team, Campbell Maclaurin, Dean’s secretary Jan Bowman, and assistant registrar Sue Cathersides.

Peter Barrie Herdson (c. 1933-2004): Pathology 1968-85

Peter Herdson initially trained as a pharmacist in Auckland before completing his medical degree at Otago in 1959, spending his final year in the Auckland Branch Faculty class. After postgraduate training in London and Chicago he returned to Auckland as foundation professor of pathology in 1968. Vice-Chancellor Colin Maiden later recalled that Herdson:

had been the Chemist up at Ranfurly Road at Waymouth’s Chemists when I was a boy. And there he was, the big Professor of Pathology.

Others also recalled him as a big man physically, and in his achievements.

One of the inner circle of leaders during the early days of the Auckland Medical School, Herdson set exacting standards. According to one of his colleagues, Sir John Scott, the Department of Pathology was the `political powerhouse’ at that time, a view endorsed by foundation Physiology Professor Jack Sinclair in a later interview.

Jack Sinclair on Peter Herdson

When the Pathology Block, which also accommodated the Auckland Division of the Cancer Society, was opened in September 1978, the medical student magazine Quack praised the way in which Herdson had brought together the competing interests of the Auckland Hospital Board, the Justice Department, the City Council, the Cancer Society, and the University.

Peter Herdson was also actively involved in cementing ties between the New Zealand Society of Pathologists and their Australian counterparts. He was one of the earliest New Zealand councillors of the Australian Royal College and became its Vice President in 1979, the year before it was renamed the Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia. As the first New Zealand president, from 1983-5, he helped establish training programmes in Hong Kong and Saudi Arabia, which led to his departure from Auckland in late 1985 to take up the position as Professor and Chairman of Pathology at the King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre, Riyadh, and editor-in-chief of the Saudi Annals of Medicine. Herdson spent the last decade of his career in Canberra, from 1991-2000, during which time he served as President of the World Association of Societies of Pathology 1993-5. The `big professor’, as Colin Maiden dubbed him, had certainly made his mark on the world of pathology.

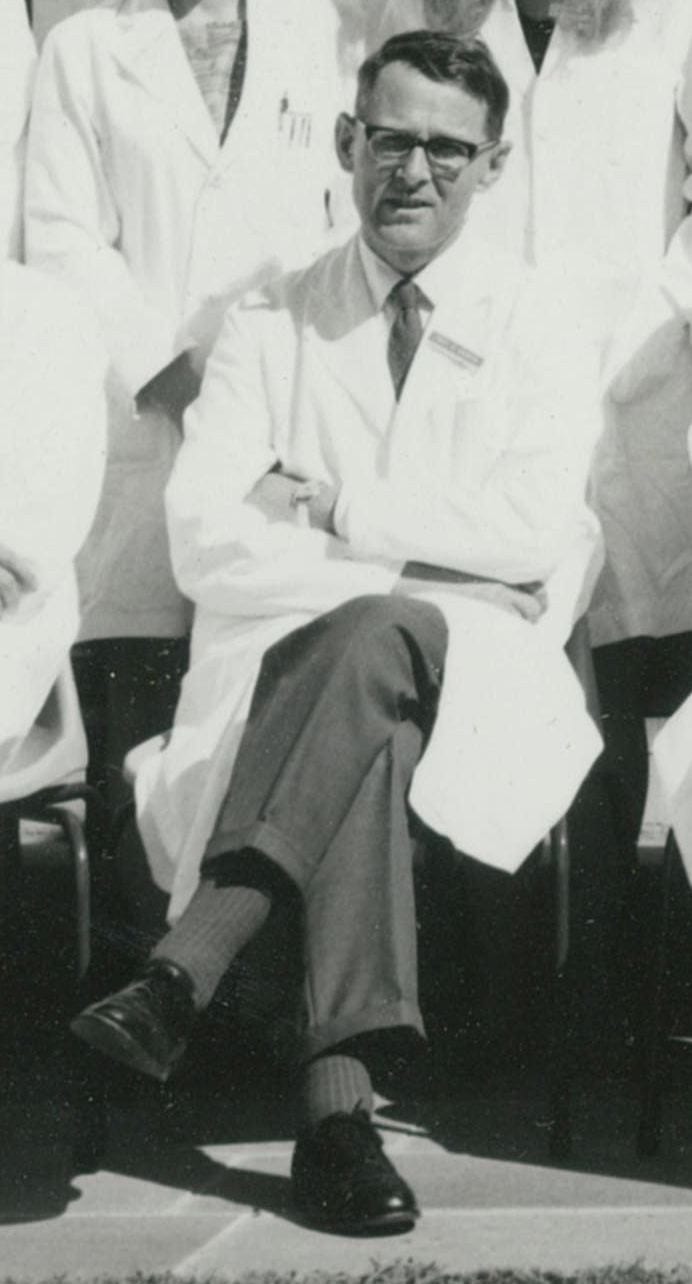

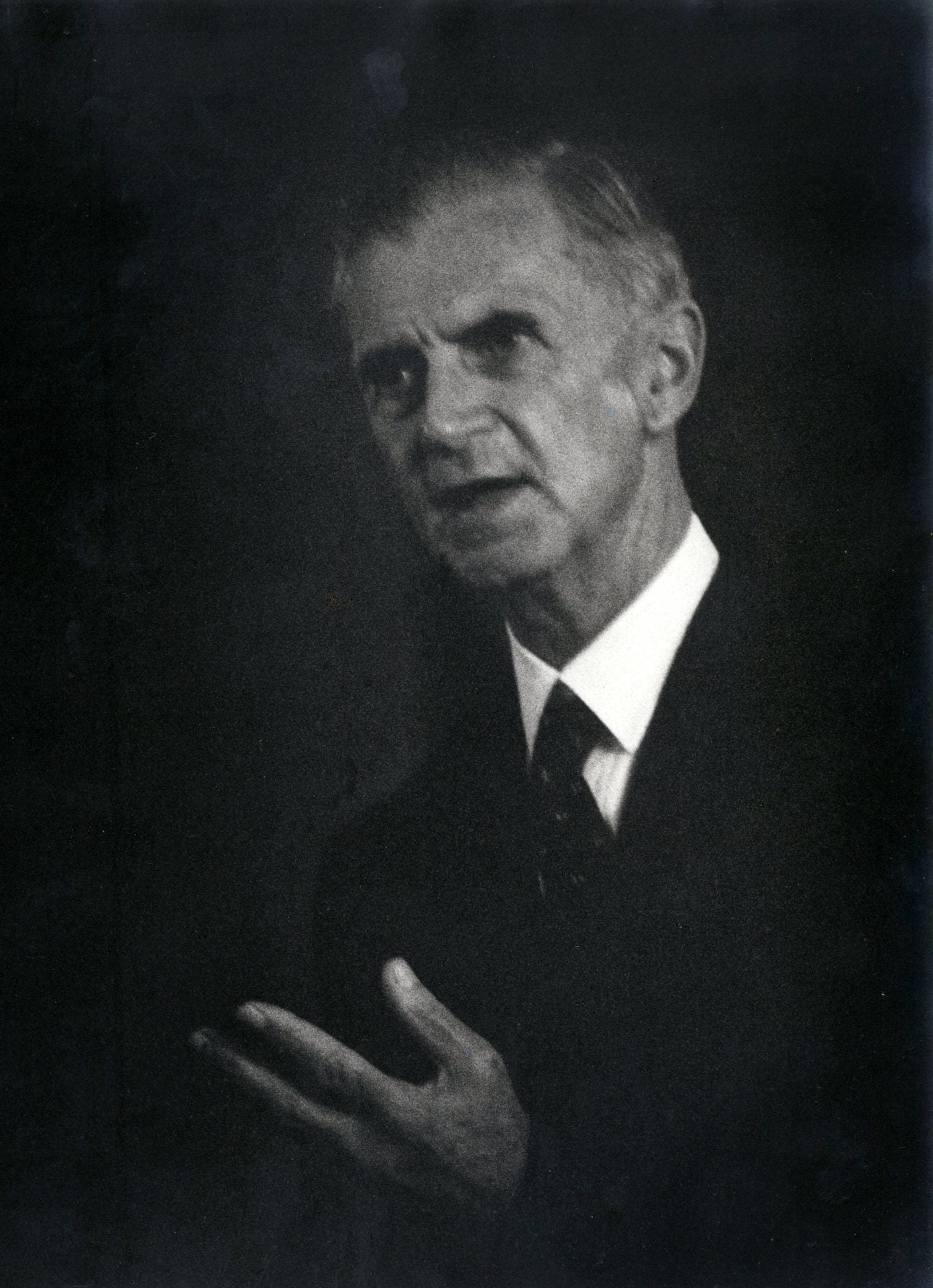

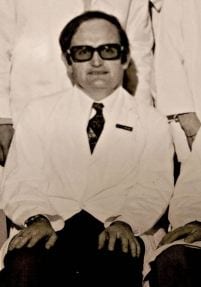

Professor Peter Herdson, 1971.

The medical student magazine in 1978 portrayed Professor Herdson defending his Pathology Department fiefdom against all intruders.

Eric Musard Nanson (1915-88): Surgery 1970-79

Although Professor Eric Nanson, foundation professor of surgery at Saskatchewan 1954-70, had turned down the opportunity to apply for the deanship at Auckland in 1965, he did agree to fill the post of foundation Professor of Surgery in 1970. Three years older than Dean Cecil Lewis and at least a decade older than the other foundation staff, Nanson offered a mature, experienced leadership for the first decade of the Auckland Medical School’s existence, until he retired in 1979.

Like a majority of the early staff, Nanson was a New Zealander, the son of an Anglican vicar based in Canterbury. After graduating in medicine from Otago in 1939 he served in the New Zealand Medical Corps from 1941-5 before postgraduate training at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London and Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. One of the features of Nanson’s career was his wide-ranging research and publication record. In 1962 he was a signatory of the articles of incorporation of the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology and was elected the fourth President in 1964. Two years later he was one of the expatriates to feature in the 1966 Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, along with a number of distinguished medical men such as plastic surgeon Harold Gillies and anaesthetist Robert Macintosh.

In 1972 Nanson was convener of a sub-committee to draw up proposals for a university course in nursing, something which only came to fruition in 1999, long after his departure.

Nanson was a talented and respected teacher, but he was also a product of his age and perhaps not best suited to the changing ethos of the 1970s. Interviewed in 2014, foundation Professor of Paediatrics Bob Elliott commented:

The student protest movement was alive and well. It never got to be extreme, but young people were taking a break from the past and they were turning up for lectures in tank-tops and beards and long hair. Much to the disgust of Eric Nanson, he just couldn’t tolerate it.

Professor Eric Nanson, 1971.

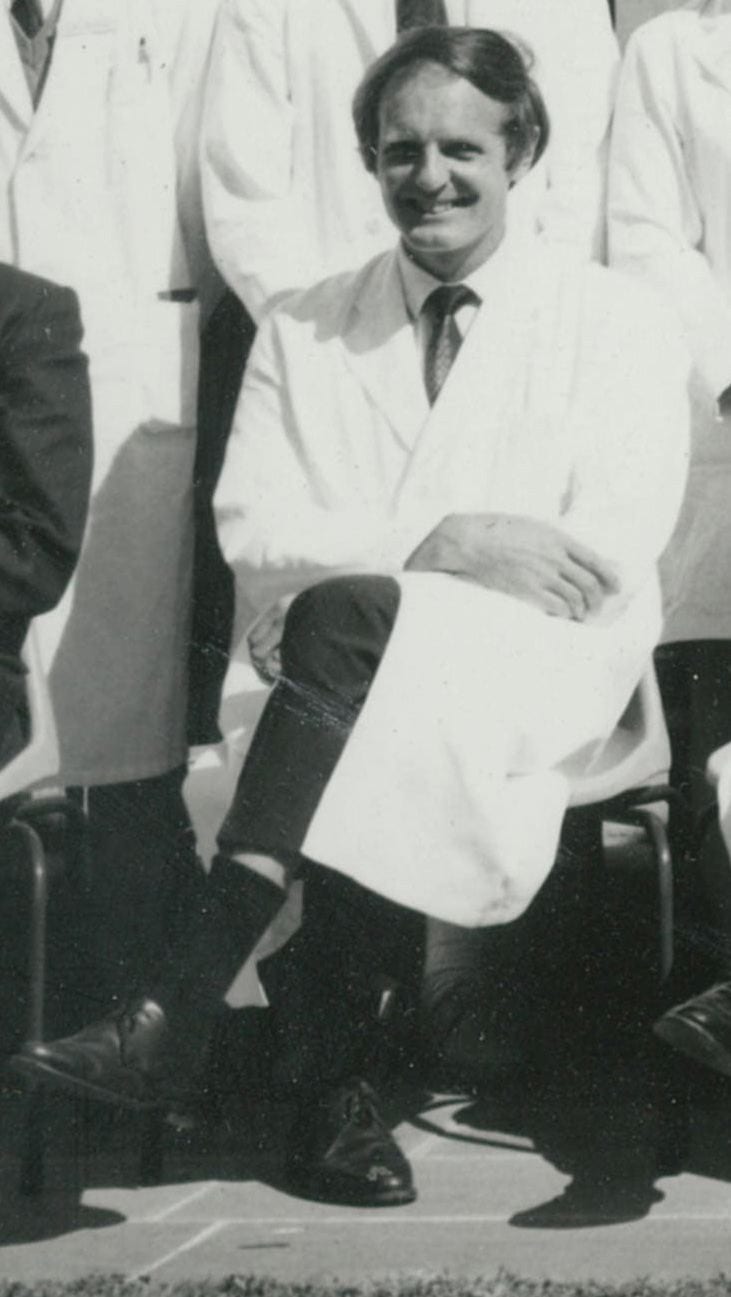

Robert Bartlett Elliott (1934-): Paediatrics 1970-99

Bob Elliott was born in Adelaide and qualified in medicine there in 1955. He was one of the few non-New Zealanders appointed to the Auckland Medical School in the early years, though he did have some prior experience of the country, working as a house surgeon in Blenheim soon after graduating. Elliott then undertook paediatric training in Adelaide and Denver, Colorado, before returning to Adelaide as a senior lecturer in 1963.

Six years later he applied for the foundation in chair in Auckland and later recounted a somewhat bizarre preliminary interview at Adelaide Airport with a jetlagged Cecil Lewis, who was en route from England to Auckland.

Although the salary on offer was less than he was already paid in Adelaide, Elliott accepted the position, though with some reservations and with his wife’s reluctant agreement on condition that this was not a long-term commitment.

Bob Elliott on moving to Auckland

From the outset Elliott devoted his energies to both teaching and research, revealing in a 2014 interview that:

I managed to get both things going. In fact, I was the first person to lodge a research publication in the Philson Library out of the new medical school. I felt a certain pride in that. Because what we were supposed to do, if we published anything a copy had to go to the Philson Library. So we managed to get research going despite the difficulties.

Elliott’s research value was recognised in 1977, when he was designated Professor of Child Health Research, taking over from fellow-Adelaidean David Lines; Lines, who had been the first incumbent in 1974, returned to Australia in 1977 as a senior lecturer in paediatrics at Flinders University.

Despite his wife’s initial desire to move back to Australia after five years, Elliott remained in post for almost three decades, retiring in 1999, the year in which he co-founded Diatranz, a company intended to commercialise research into treatments for type 1 diabetes. In 2003 the company was renamed Living Cell Technologies.

As John Werry, foundation Professor of Psychiatry, remarked in a 2014 interview, Bobby Elliott:

was I think a good head and the Department of Paediatrics is I think one of the ones who’s done best in the Medical School.

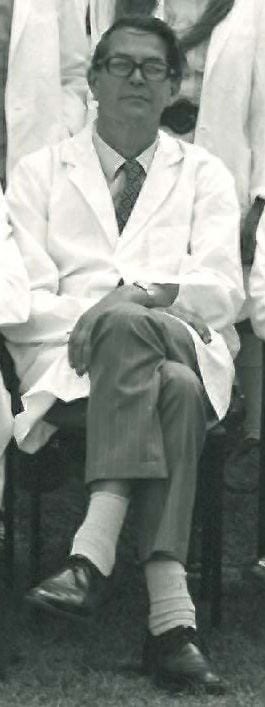

Professor Bob Elliott, 1971.

Henry Kaye Ibbertson (1927-2018): Endocrinology 1969-92

Kaye Ibbertson’s career was closely linked with that of his `friendly rival’ Derek North. The two had been contemporaries at King’s College in Auckland and during their medical course shared quarters at Knox College in Dunedin. When they returned from postgraduate training at Hammersmith Hospital in London, Ibbertson succeeded North in 1959 as medical tutor to the final year Otago students based in Auckland, while North became physician-in-charge of the Full-Time Medical Unit. Together, the two men presided over what North’s obituarist described as `an age of enlightenment’ in Auckland medicine.

In the mid-1960s Ibbertson established a Department of Endocrinology at Auckland Hospital, having been trained in the discipline during his time in London by expatriate New Zealander Russell Fraser. From the outset, he vividly demonstrated the value of his chosen field. In 1965 he and Mont (later Sir Graham) Liggins were jointly responsible for the fertility treatment which resulted in the birth of the famous Lawson quintuplets, and the next year he made a major breakthrough in treating thyroid disease in Nepal, working with Sir Edmund Hillary’s Himalayan Trust.

At home, Ibbertson’s research fed into his teaching, which made a strong impression on the first group of students. In his 1968 diary first year student Steve Culpan graphically recorded this impact:

From here we went to the Auckland Hospital, This was the first time we were to have any real connection with the hospital that will become a very big classroom for us in the future. It was appropriate that for the first of a long line the programme should deal with growth and development; and the isolation and preparation of growth hormone extracts for the treatment of people suffering from various degrees of growth hormone deficiency. The doctors concerned in the mosaic style seminar were Drs Ibbertson, Scott, and Costello.

Through his teaching Ibbertson laid the foundations for the very successful Auckland Bone and Joint Disease group and other enterprises, mentoring many of Auckland’s leading medical scientists, including Deputy Dean Distinguished Professor Ian Reid and Professor Garth Cooper.

Contributions beyond Auckland included roles as a foundation member of the New Zealand Society of Endocrinology, and of the Australian and New Zealand Bone and Mineral Society. In 2005 the latter organisation instituted the Kaye Ibbertson Award for Bone and Mineral Medicine in honour of his `outstanding career and major investigations into skeletal disorders’.

When news broke of Professor Ibberson’s death in July 2018 the Auckland Medical Research Foundation, another body in which he had played a leading past, recorded the following tribute:

The contributions he made throughout his career to osteoporosis research, thyroid disease, growth disorders in children, and endocrinology education have helped countless people worldwide.

Kaye Ibbertson pictured in 1959 in his role as medical tutor. Two of the students in this year, Peter Herdson and Rex Hunton, became fellow teachers in the early years of the Auckland Medical School.

Garth Cooper on Kaye Ibbertson

John Scott Werry (1931-): Psychiatry 1970-91

After graduating from Otago in 1957 John Werry studied psychiatry in Canada and the USA, where he became head of the Institute for Juvenile Research in Chicago. When the Auckland Medical School opened in 1968 Dr Roger Culpan provided teaching in psychiatry until the University recruited its foundation professor. In 1969 Vice-Chancellor Kenneth Maidment visited Werry in Chicago to sound him out about applying for the post. Many years later Werry revealed he had been on a shortlist of two and that the other candidate, Eugene Paykel of the Fisher and Paykel dynasty, ruled himself out after being offered the chair of psychiatry at Cambridge University. (In fact Paykel initially went to St George’s Hospital Medical School in London and only transferred to Cambridge in 1985.) In 2014 Werry downplayed his own merits, with a story – perhaps apocryphal – of Dean Lewis’s reaction to his appointment.

John Werry on Cecil Lewis's perception

Werry became an international authority on child and adolescent psychiatry and a founding trustee of the Youth Horizons Trust for severely behaviourally disturbed young persons. In 1974, with his colleague Rex Hunton, he was also instrumental in setting up the controversial Auckland Medical Aid Centre (AMAC) to provide abortion services at a time when abortion was still illegal except to save the life of the mother.

Werry’s stated goals, recounted in a 2014 interview, were to be a good colleague and to `teach a psychiatry that represented the best in scientific psychiatry that we were able to master for that time, and then to try to impart that view to the students’. One measure of his success was that Michael Aman, his department’s first PhD student, went on to be Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry at Ohio State University.

Throughout his career Werry was determined to `do what is right rather than follow rules’, a belief which explained his agreement to perform terminations despite the very real risk of prosecution.

Speaking in 2014, he summed up his contribution in a typically pithy manner:

I’ve provided a certain degree of colour in Medical School. There are an awful lot of drab, conventional people in the Medical School. I’m a larrikin!

John Werry, pictured in 1971.

Arthur Milton Oliver Veale (1926-87): Community Health 1971-87

Arthur Veale qualified from Otago in 1950, the same year as three of his future Auckland Medical School professorial colleagues, Kaye Ibbertson, Derek North and Jack Sinclair. Unlike the others, Veale did not complete his final year in the Auckland Branch Faculty. In 1965, however, Veale was consulted by the Auckland Senate Advisory Committee on the proposed medical curriculum.

By the late 1960s Veale was director of the Medical Research Council’s Human Genetics Research Unit in Dunedin and a member of the WHO advisory panel on human genetics, with a growing reputation for his work on multiple screening of babies against inherited diseases. In 1972, when Dean Cecil Lewis was on leave, Veale was reputedly head-hunted by Acting Dean David Cole to fill the foundation chair of community health in Auckland, a position which Lewis had apparently wished for himself.

Four decades after the event, Vice-Chancellor Colin Maiden suggested that the then Chancellor Douglas Robb had also had a hand in affairs:

Douglas Robb was very keen on Arthur, he’d known his father, who was apparently a well-known doctor.

While Percy Veale and Douglas Robb had both been University Scholars at Auckland in 1917 they followed different career paths, with Veale going on to become a respected dairy scientist in Taranaki.

Veale’s appointment coincided with the announcement of plans for the Mangere Health Centre, which opened in 1974. The Centre was intended to incorporate genetic counselling, as well as child care and family planning facilities. By 1981 Veale had also laid the foundations of the brain bank, which has evolved into the University Centre for Brain Research.

Arthur Veale died suddenly on 6 November 1987. His successor in the chair, Robert Beaglehole, described him in the University News as `a great champion of community health’. Others were less convinced. Professor Bruce Arroll believed Veale’s appointment had delayed the evolution of general practice as an academic discipline.

This was reflected, and partially explained by a comment in a 2008 interview by Professor Jack Sinclair, foundation Professor of Physiology. Sinclair recalled that Veale, who was a contemporary and a friend, had admitted five years after his appointment:

`Do you know, I’ve just realised what Community Health ought to be.’ And he rattled off the things I would have said if I’d been interviewed for it.

Other Foundation Staff 1967-74

In addition to the foundation professors a steady stream of other staff were enlisted in the early years of the Medical School. Graham White’s role as the first lecturer to be appointed is outlined elsewhere. White’s teaching role in the pre-clinical years was bolstered by two other appointments. He and John Duder, a temporary junior lecturer in 1968-9 then a lecturer in the Physics Department until 1979, formed an effective team for the physico-chemistry component. Duder was also supportive of the MAPAS scheme from its inception. After his resignation Duder moved to the USA where he was involved as Deputy Commissioner in revamping the California State IRD; he later helped devise computer systems for the launch of Obamacare.

Biology teaching for medical students was entrusted in 1968 to Peter Jenkins (1926-2012), who taught within the School of Medicine for 20 years before transferring to the Zoology Department. Jenkins was a foundation trustee of the New Zealand Native Forests Restoration Trust in 1980 and its secretary during the formative years. Like many other Medical School staff, he had the pleasure of seeing his son, Ian, graduate MB ChB Auckland, in 1985.

Physiology, another core component of the curriculum, was supplemented in 1969 by the appointment of Royce Farrelly as associate professor to work alongside Jack Sinclair. Farrelly, who had initially been recruited to the Auckland Hospital Medical Unit by Derek North to study the physiological aspects of renal disease, remained in post until his retirement in 1983. He helped Graham White to construct the physico-chemistry course in the early days of the School.

The Anatomy Department was another to enjoy an early expansion. Denys Boshier (1929-) was recruited from Massey College in 1969 as an associate professor in the Departments of Anatomy and Physiology to teach reproductive biology, a task he undertook until his retirement in 1992. In a 2017 interview Boshier proudly described one of his early classes:

In the first year that we were on the site the Queen came to open the School, and of course we were all primped and primed in preparation for that, and she actually came into one of my classes. That was 1969, the first year in which I had my own course in Human Reproduction and Development, and I thought it was improper to change my timetable within the teaching programme just because the Queen was there.

After his retirement Boshier became chairman of Probus New Zealand Inc, part of a movement formed in 1965 in the UK to bring together retired or semi-retired individuals from all walks of life.

A second associate professor was appointed to the Anatomy Department in 1970, emphasising the importance of the subject to medical education. Kingsley Mortimer – like his colleagues Jack Sinclair and John Scott – was a former pupil of Auckland’s Mount Albert Grammar School. Mortimer, who qualified MRCS LRCP 1943 in London, had been a Salvation Army missionary in Rhodesia. In 1964 he was an examiner in anatomy and physiology in Perth, Western Australia, where he may have come to the attention of Cecil Lewis, Auckland’s first Dean of Medicine.

In 1975 Mortimer completed a Diploma in Psychiatry and left the Medical School to be founding head of the psychogeriatric unit at Carrington Hospital. Following his death in 1980 Mortimer’s widow established the Kingsley Mortimer Memorial Prize, awarded annually to the full-time student who achieved the highest mark in the practical skills tests for the MB ChB Part II.

The Pathology Department could claim to have recruited the most travelled of the early staff. In 1969 John Arthur, a London medical graduate, accepted the position of Associate Professor of Anatomic Pathology and histopathologist-in-charge, Auckland Hospital. Arthur married registered nurse Heather Coleman, a fellow sailing enthusiast, on 20 August 1969 and within 3 weeks the couple set sail for Auckland on board their 38-foot yacht, arriving in the City of Sails on 31 May 1970. Arthur was one a clutch of pioneer staff to retire in the early 1990s, after which he worked at Diagnostic Laboratories for a number of years.

The Pathology staff grew rapidly in the early days, with two additional associate professors – John Bevan Gavin (1935-2018) in 1970 and John Gordon Buchanan (1932-), a haematologist, in 1971. There was another addition to the Pathology staff in 1971 with the appointment of David Bremner as senior lecturer in microbiology, a year after he returned from a decade in Melbourne.

Surgery was also expanded in 1971 with the appointment of two senior lecturers, both Otago graduates. Ronald Kay later specialised as a breast surgeon and chaired the Breast Cancer Foundation of New Zealand’s Medical Advisory Committee for its first 6 years. The second appointee, Trevor Doous was yet another Mount Albert Grammar Old Boy. Winner of the Sir Carrick Robertson Surgical prize in his last year at Otago in 1956, he was a surgical researcher in the UK from 1962-70 before accepting the Auckland post. His promotion to associate professor in 1973 was short-lived as he died in June 1975, aged just 43.

In Medicine, John Scott, who had been strongly encouraged to return from Britain by Sir Douglas Robb, was accorded the status of honorary senior lecturer in 1970 before being elevated to associate professor in 1973. The prospect of confusion within the department rose sharply in 1971 with the appointment of two more Scotts, Alistair and David, as senior lecturers, along with Cliff Tasman-Jones, who was elevated to an associate professorship three years later. Ian Simpson, a future Deputy Dean of Medicine, also joined the Department in 1971, though he did not become full-time until 1978.

The Psychiatry Department was strengthened in 1969 by the appointment of Associate Professor William Richard McLeod (1933-), a Melburnian and the second Australian to join the staff. McLeod was elected to Senate as a representative of the sub-professorial staff in 1974, the first from the Medical School to fulfil this role.

McLeod was followed by a third Australian in 1973 when David Robin Lines (1937-) was appointed to a research chair in child health, working alongside his fellow Adelaidean, Professor Bob Elliott. McLeod and Lines both returned to Australia in 1977, with Lines taking up a senior lectureship in paediatrics at Flinders University, thus highlighting the financial gap between the two countries when it came to academic posts.

The importance of behavioural science in the Auckland curriculum saw the appointment of Graham Vaughan (1934-) as senior lecturer in psychology. Born in Melbourne, Vaughan had a peripatetic childhood thanks to his father’s army career, culminating in a stint at St Peter’s College Auckland 1947-51. Promoted to an associate professorship in 1970, Vaughan resigned his Medical School post in 1973 to teach full-time in the Psychology Deprtment and was replaced by Betty Bernadelli.

Behavioural Science was closely linked to Community Health, another element in Dean Cecil Lewis’s blueprint for the new School. In 1972 Lewis’s fellow Welshman, John Skone (1924-2002), whose research had focused on the health of immigrants to Britain, spent time in Auckland as visiting professor in community health. This was perhaps arranged to counter the appointment of Arthur Veale, a geneticist, as Professor of Community Health, a decision apparently taken when Lewis was on leave.

That same year the Auckland Star reported that:

The choice of staff for the new department is interesting. One lecturer is a Catholic priest (Father Felix Donnelly) with no Medical qualifications (although he holds university degrees in criminology).

Donnelly (1929-) was something of a gamble since he was often at loggerheads with the Catholic hierarchy. On the plus side, he had founded Youthline in 1970 to meet the needs of youngsters who did not connect with traditional organisations such as the Samaritans. This outreach appealed to many medical students with whom Donnelly came into contact.

The third member enlisted to Community Health in 1972, as a senior lecturer, was Rex Hunton. He had returned from the UK to Green Lane Hospital’s cardiology unit in 1965 and then became the Otago University medical tutor at Auckland Hospital `because I had all these overseas degrees’. Hunton was heavily involved in setting up Auckland’s first abortion clinic in the mid-1970s and also helped establish links with two Northland marae, as part of his remit, in the words of the medical student magazine Quack, years to teach `the probably all-too-large field of “Polynesian health care”’.

The first member of staff charged with teaching general practice was Associate Professor John Richards (1931-) who was appointed in 1973. Richards had the ideal background for the task ahead of him. His father, a New Zealander, had undertaken his medical training at Guy’s Hospital in London just before WW1 and returned to Auckland in 1922 to as a GP in Mount Eden in Auckland. His mother, Rosina Crawley, completed her Otago MB ChB in 1921 then travelled to England to gain additional experience. In 1924 New Zealand Truth reported that `Dr Crawley, an Auckland woman, is also on the eve of returning to the Queen City, to hang out her shingle.’ Six years later she married John Richards senior.

The early years of the new Auckland Medical School were eloquently summed up in a 2017 interview with Denys Boshier, a member of staff from 1969-83.

The analogy can be carried over very much into the research work I was doing: it was an embryo developing within the placenta of those of us who were appointed very early and were responsible for its development. I really do have to pay homage and respect to Professor Cecil Lewis who was the first dean and who had a really wonderful perception of what he wanted to do and what the school might become. Because it was a major step forward within the universities of New Zealand. The development of a second medical school allowed people to learn from what had been the case in Dunedin, which was the only school of medicine at that particular time.

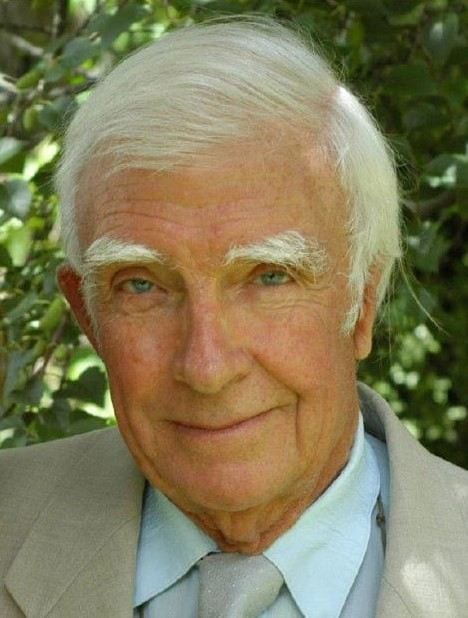

Professor Arthur Veale, 1974.

Jack Sinclair on Arthur Veale

Bruce Arroll on Arthur Veale

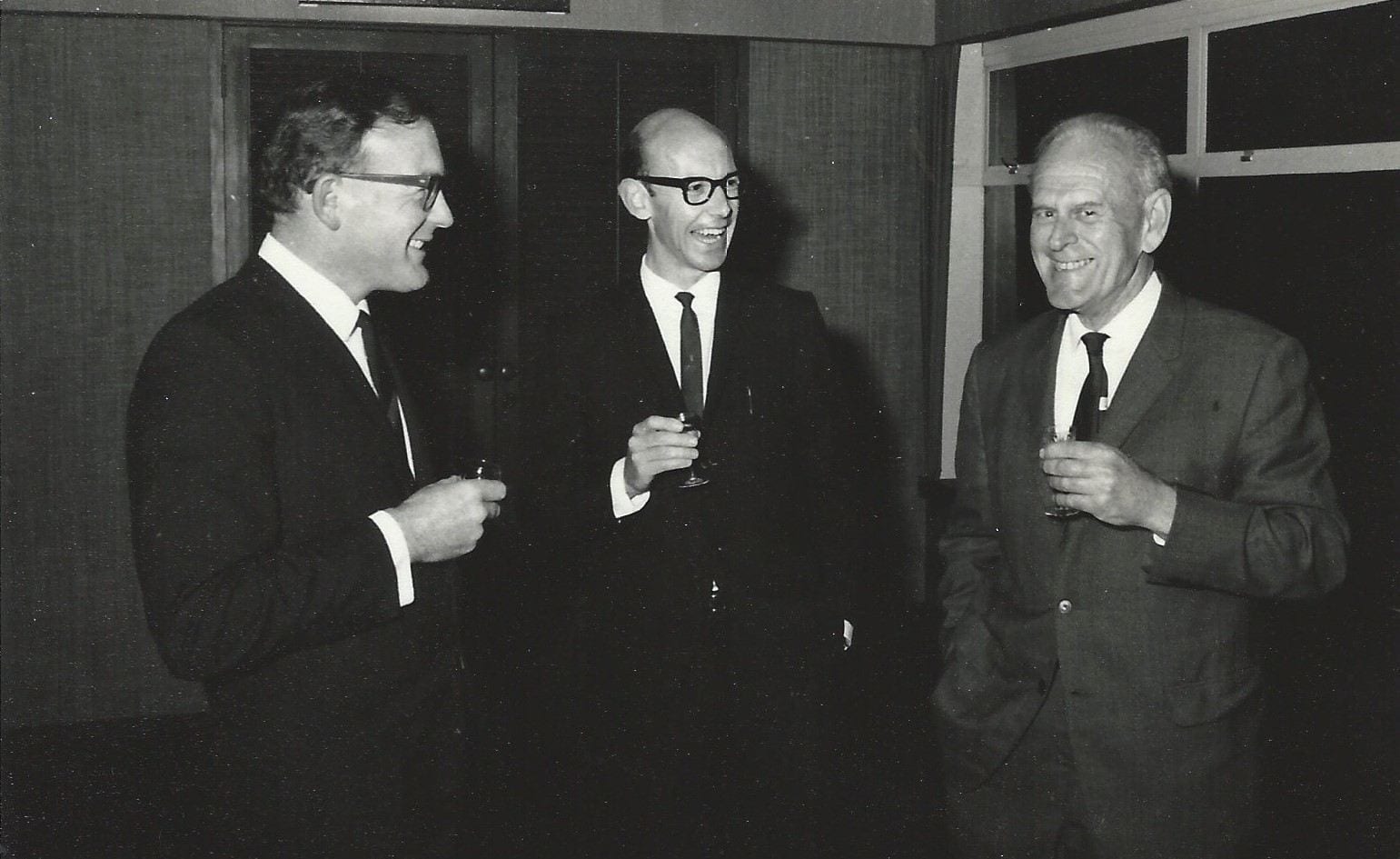

Peter Jenkins, Graham White and Associate Professor Searle, Dean of Science and a member of the Senate Medical Committee, sharing at joke at the 1968 student dinner.

During his tenure Mortimer was photographed by one of the inaugural students, Peter Charlesworth, who later described Mortimer’s response to being presented with a copy of the picture

Peter Charlesworth on Kingsley Mortimer

Bruce Arroll on Kingsley Mortimer

John Francis Arthur (1930-2015).

David Bremner, a 1957 Otago graduate who retired in 1997, was affectionately dubbed `Bremnercoccus’ by the generations of students whom he taught. His daughter Catherine graduated from Auckland in 1987 and works as a paediatrician in Whangarei.

Rex Hunton as a final year medical (back row centre) with Peter Herdson (front left), 1959.