STUDENTS

This section tells the story of the earliest admissions to the Auckland Medical School, the class of 1968.Admission to Medicine at Auckland

In August 1965 Norman King, the MP for Waitemata since 1954, drew the attention of parliament to a statement by a former BMA president that prompt action would ensure that 30-50 `young men with the requisite qualifications’, who had failed to gain entry to the Otago Medical School, could start their medical course the following year if the University Grants Committee expedited the inauguration of the Auckland Medical School. The Education Minister’s response was non-committal but the exchange raised expectations that the new venture was imminent and encouraged some students to delay their entry to medicine until Auckland was up and running.

The situation at that time was summed up by John Lindsay, one of the original 1968 intake:

I had actually applied to Otago University previously, but there was only one school and there was limited numbers, and the year that I first applied only eight students were taken from Auckland because it was rather skewed towards Otago. I couldn’t afford to go to Otago [for the Medical Intermediate], which was considered to be an easier entry pathway, so I did it up here and when I missed out the first time my next option was to proceed and do a BSc and then get in to Otago University as a graduate. However, in the intervening years Auckland University decided to start its Medical School, and I applied for the first entry.

The current headmasters of King’s College, Geoffrey Greenbank (1946-73), and Auckland Grammar, Sir Henry Cooper (1954-72), played an active part in encouraging their pupils to consider Auckland medicine. Both were members of the University Council in the 1960s and Cooper was pro-Chancellor during this critical period. John Faris, another 1968 entrant, recalled in a 2017 interview the impact that Greenbank had upon his decision to apply.

News of the imminent opening persuaded Grammar pupil Chris Diggle to spend an extra year at school, studying scholarship biology in preparation for 1968. In total about a dozen of the original intake had begun university prior to 1968, often in the hope of gaining entry to the medical school when it opened. John Faris later commented that teachers such as Graham White allowed them some latitude in the initial stages; instead of repeating the basic sciences they were encouraged to take classes such as radiochemistry, and to `start dabbling in computers’.

Although Norman King had talked only of `young men’ entering medicine, girls were also attracted. Innes Asher, daughter of the University of Auckland’s Professor of German, was reluctant to commit to the Otago course because at that time she `wasn’t actually aspiring to be a doctor’, and was more interested in human biology. The more flexible structure of the Auckland course clinched the decision for her.

There were a lot of discoveries going on with DNA and its applications and human genetics. They were very exciting times, so when the Medical School opened and they said you could do a Bachelor of Human Biology for the first three years and then leave if you wanted to, that attracted me to apply and I was glad I got in. And then I just gradually became interested in medicine once I was in the Medical School.

The choice proved to be a good one. Asher, a former head girl at Auckland Girls Grammar School, won the Lt Eric Hector Goodfellow Memorial Prize at the end of her 3rd year and topped the first graduating class as the first recipient of the Douglas Robb Prize at the qualifying ceremony on 20 November 1973.

Competition was fierce for entry to the new school, with 260 applicants for the 60 places on offer in 1968 – an increase from the initial plan to admit just 50. The applicants included 11 duxes and 10 who had been head boy or girl of their school. At the end of the selection process 48 males and 12 females were admitted to the course starting in March 1968.

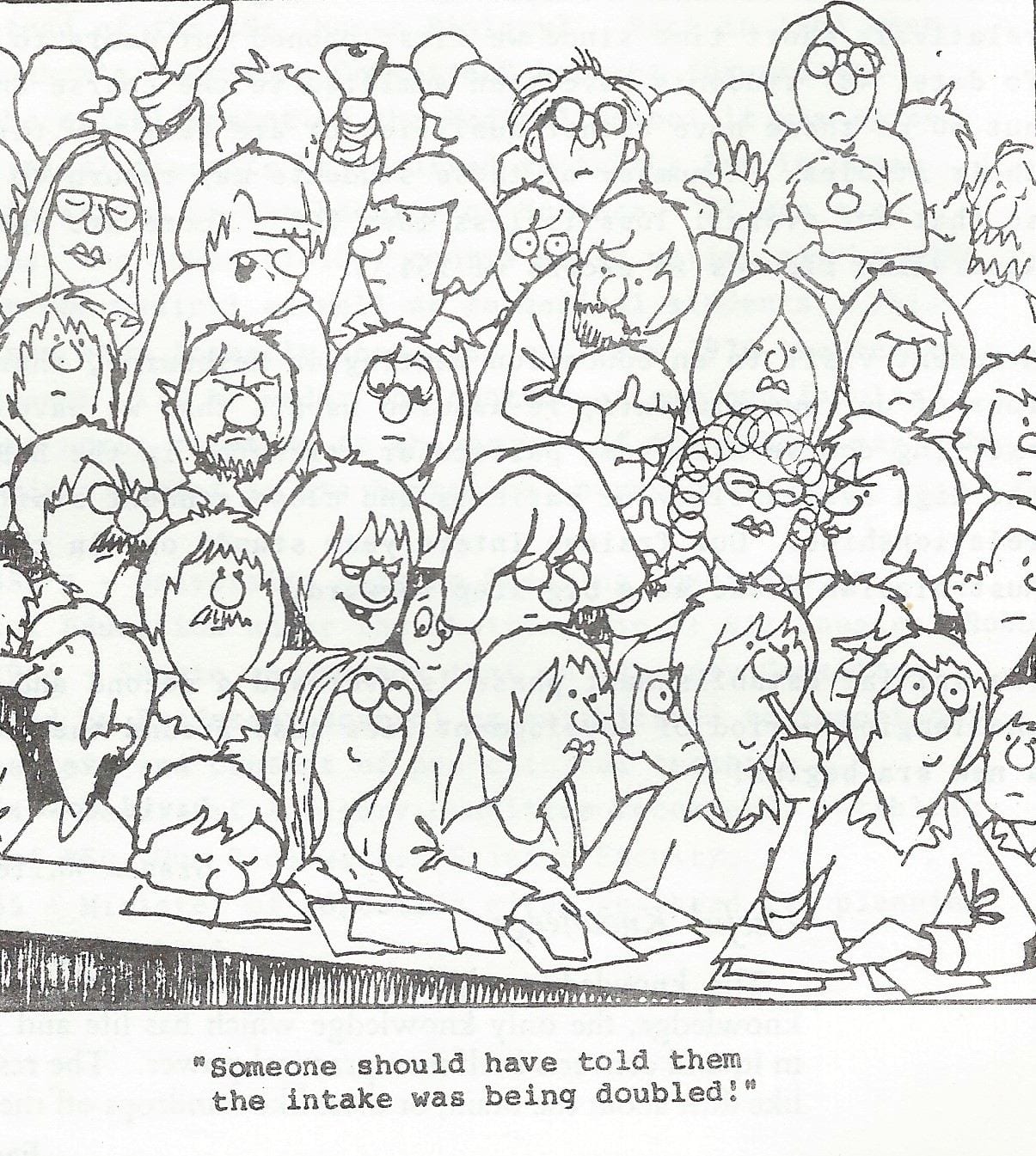

Writing for the University Gazette in November 1967, Dean Cecil Lewis revealed that Auckland would ultimately produce 100 doctors each year. In 1975 it was agreed to double the number admitted to the School, from 60 to 100.

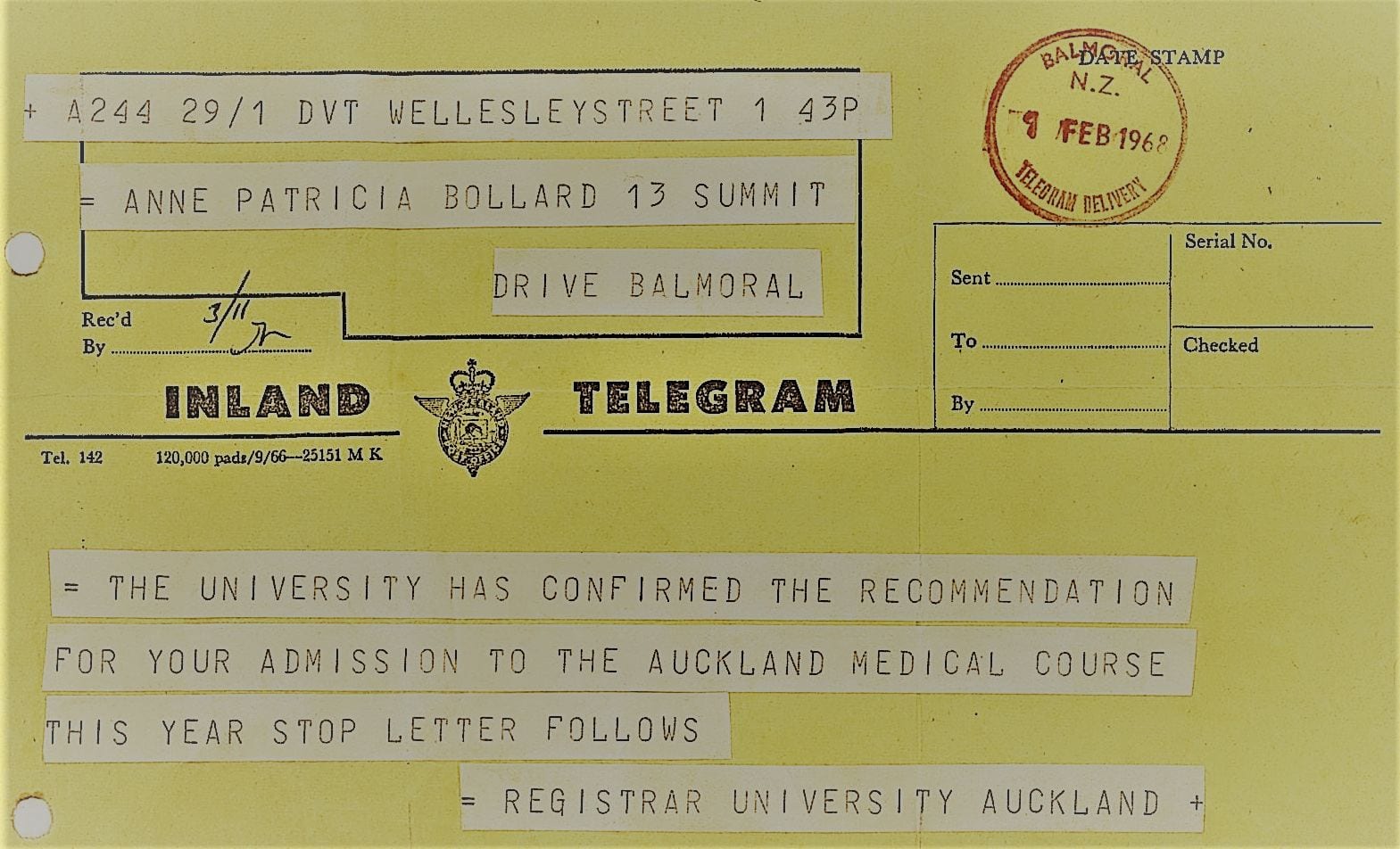

The admissions process in 1968 was fairly hurried, with successful candidates informed by telegram just weeks before the academic year began on 26 February 1968.

John Faris on choosing Auckland

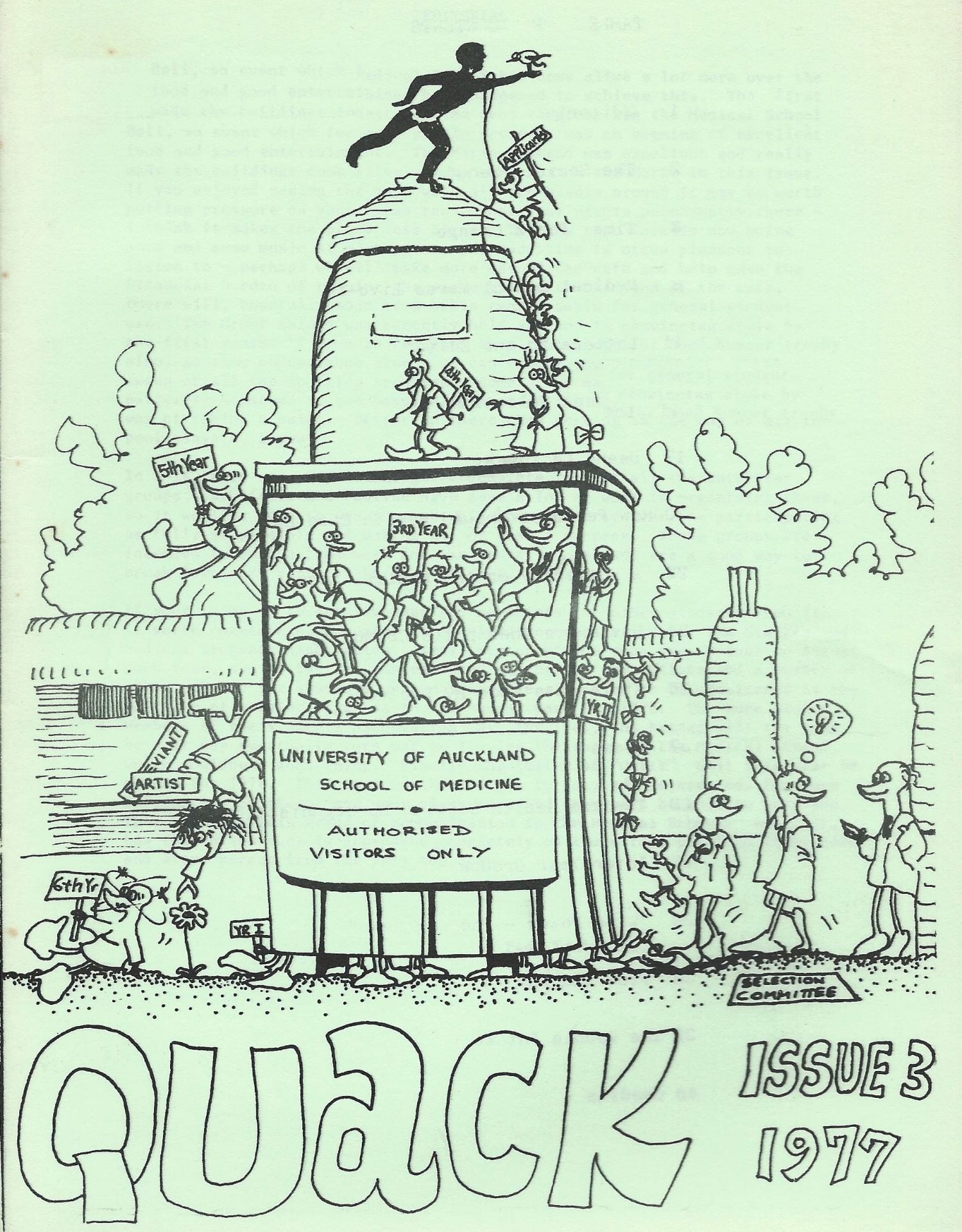

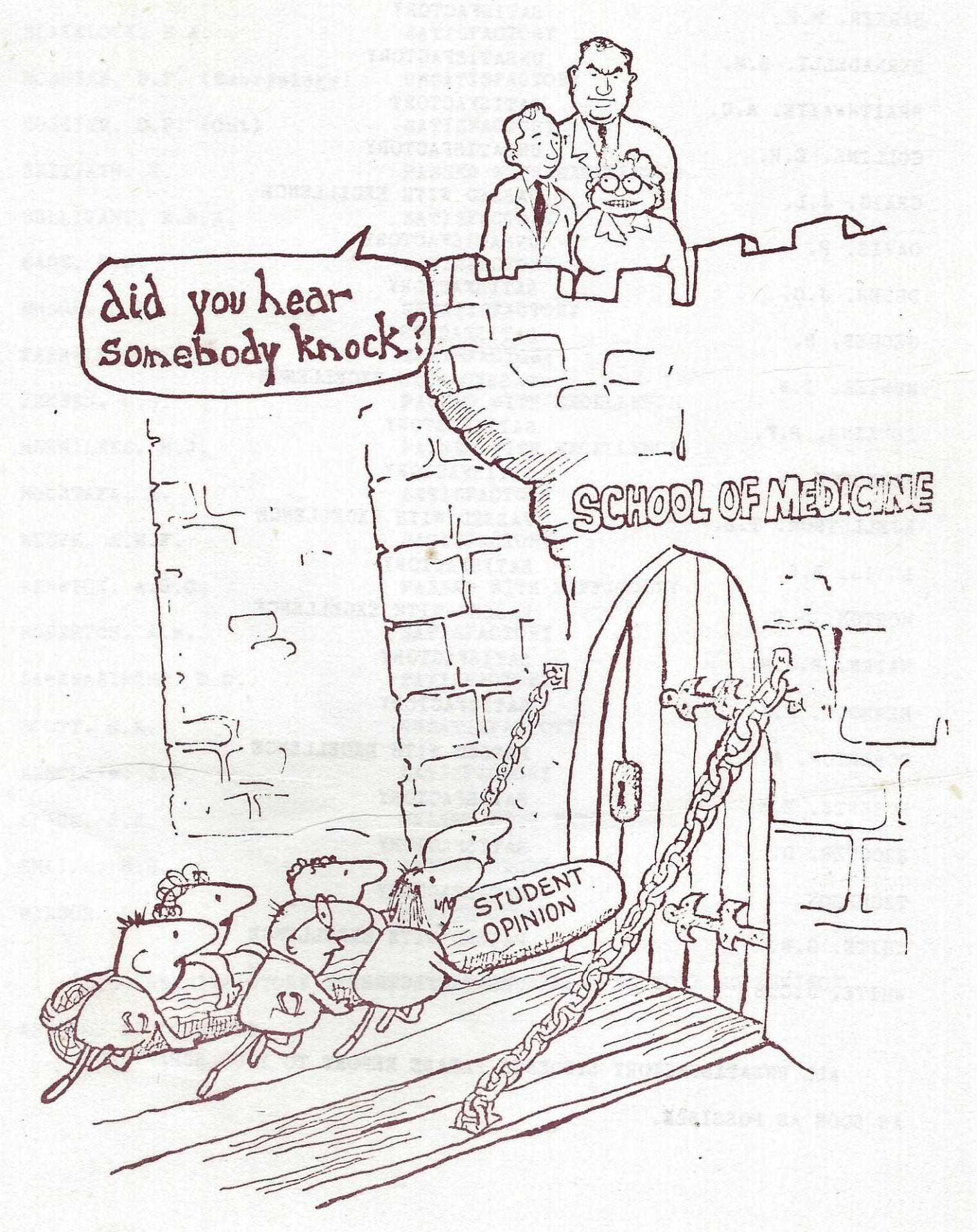

The medical student magazine QUACK published a cartoon in October 1975 expressing reservations about the increased admissions. A harassed-looking Dean Cole, with his trademark glasses and fly-away hair, is standing at the back, surrounded by blank faces.

The Selection Process

Unlike Otago, the Auckland Medical School did not adopt the medical intermediate year, preferring to accept mainly school leavers. Selection was primarily on the basis of bursary or scholarship marks, although Dean Cecil Lewis introduced some caveats. Entry was not to be restricted solely to those with a science background but was open to candidates with good academic standing in any field of study. Secondly, Lewis insisted that all prospective candidates be interviewed, and that he would sit in on each and every session.

Making the case for the value of an interview in 2008, three Auckland academics – all graduates of the School – reported the widely-held belief that Lewis had adopted this course in order to identify the `bad buggers’, a sentiment with which the three authors agreed. Interviewed in 2017, Felicity Goodyear-Smith, another early graduate who progressed to occupy a chair at Auckland, made the same point: `The interview I’ve discovered basically is to discover if you’re a psychopath.’ Sir John Scott, one of the early appointees to the staff, phrased it more diplomatically: `Generally medicine needs people who are warm and empathic.’

Physico-chemistry lecturer Graham White, who was part of the admissions’ team for many years, has recounted how intimidating it was for the first applicants to be confronted by `four or five older men in suits’. Despite this deterrent he reckoned that the interview rarely affected the ranking of the applicants, an opinion shared by many of the early staff looking back on their experiences as interviewers. In 1977 the medical student magazine Quack queried whether the rankings were significantly affected by the interview, with the anonymous author postulating that the interview `holds its place as a staff morale booster, (they do like talking to those young people)’.

Some prospective students were better prepared than others. James Church, a member of the first class, was the son, grandson and great-grandson of New Zealand doctors and remembered `being schooled on what to say and stuff by my Dad’. Former Auckland Grammar boy Chris Diggle impressed with his account of his duties as a bus prefect:

And I suppose military-style I gave a very short sharp answer, just to make sure there’s no nonsense on the bus. And he [the interviewer] sat back in his chair and he smiled.

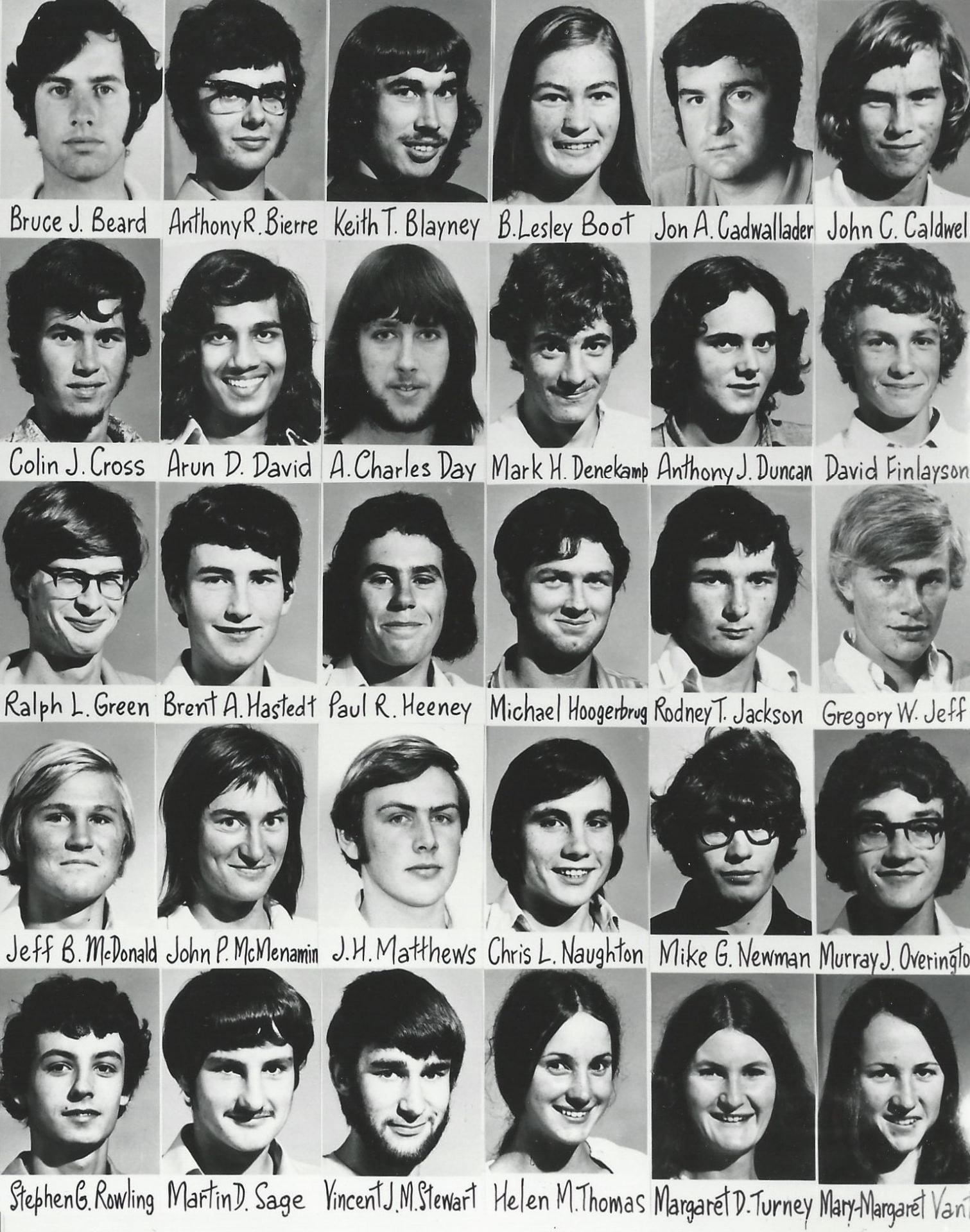

Future Distinguished Professor and Deputy Dean Ian Reid, who entered the medical course in 1972, found the interview `not particularly daunting’ since he was confident that his scholarship marks would carry him through. Another future professor, Bruce Arroll, remembers being asked in his interview for admission in March 1973 `What does Watergate mean?’ Fortunately `I’d actually asked myself that question a couple of weeks before, and recognised it was the name of a hotel in Washington DC where it all happened. So I was able to come out of the interview feeling pretty good.’ (The Watergate break-ins at a Democratic Party office occurred in June 1972 and the affair dragged on until President Richard Nixon was forced from office in August 1974.)

Over the years the format of the interviews changed. The interviews were extended from 15 to 25 minutes while the number of interviewers was reduced, to a pairing of a clinician and a non-clinician. They were more structured than in the early days, looking to assess candidates for maturity, communication skills, awareness and knowledge, career choice, and well-roundedness.

The 2008 survey by Des Gorman, John Monagetti and Phillipa Poole also revealed that the interview

provides some applicants an opportunity to `self‐destruct’ without loss of face and in a way that avoids conflict with parents, significant others, teachers and so on, many of whom might have a clear, but, unilateral ambition for the person to become a doctor. Every year, we see a number of such self‐destructs. The interview is often the first and only opportunity for a naturally gifted young person to opt out of medicine; for example, since a day early in their secondary school life when a teacher remarked to their parents that they were `bright enough to do medicine’.

A follow-up in 2012, published in the New Zealand Medical under the title `Shedding light on the decision to retain an interview for medical students’, concluded that the current system had `no predictive validity in terms of predicting achievement later in the medical programme, withdrawal, or failure to complete Year 4 on time.’

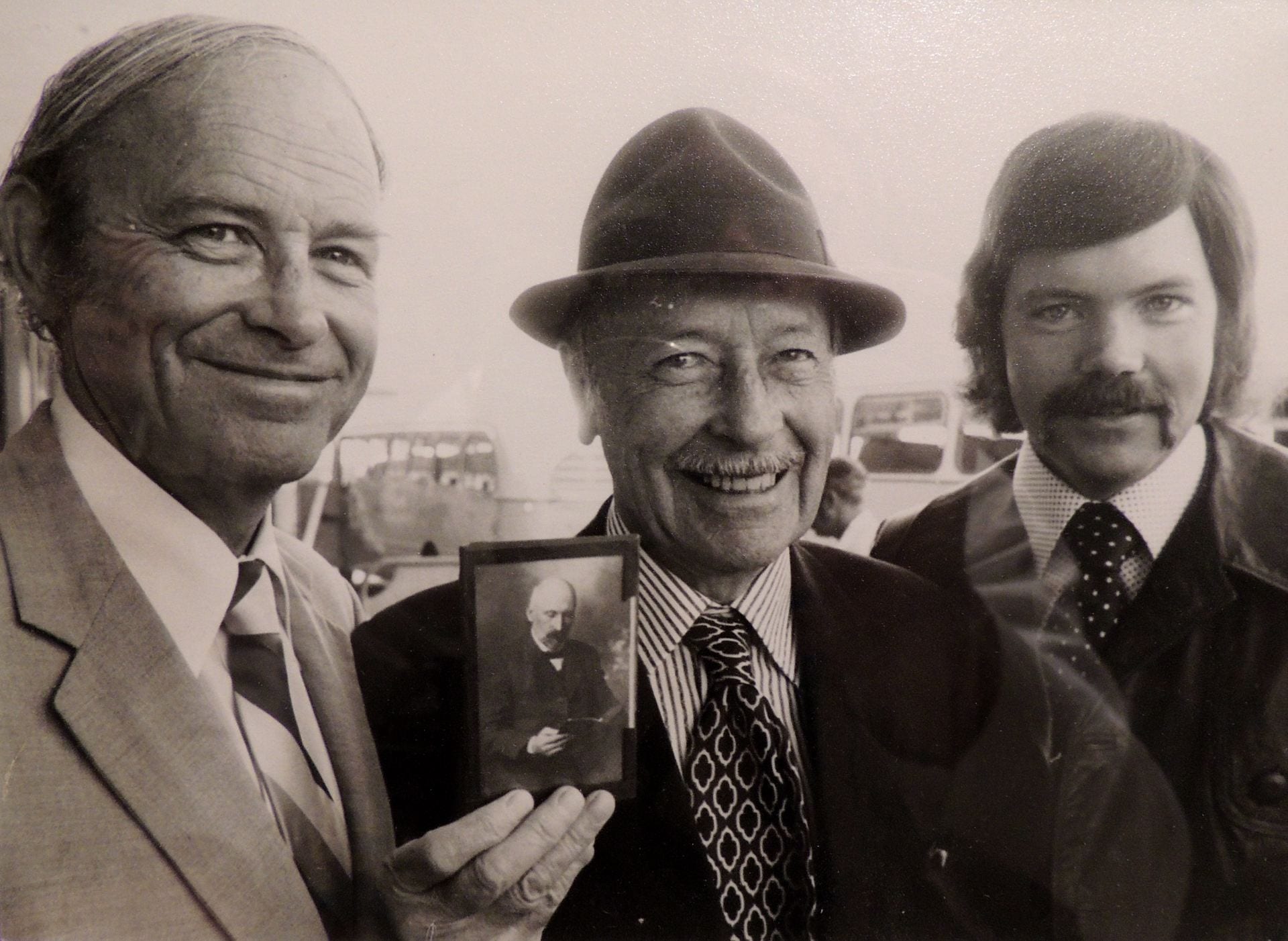

Of the 60 students who began their studies in 1968, at least 11 were the offspring of doctors. Pride of place goes to James Church, seen here at his graduation with his father, grandfather, and a photograph of his great-grandfather. Grandfather Robert Church won the Military Medal at Gallipoli while serving as a student in WW1 and graduated in the same class as Douglas Robb in 1922. He died in May 1974, shortly after this photograph was taken.

Ian Reid on the Interview Process

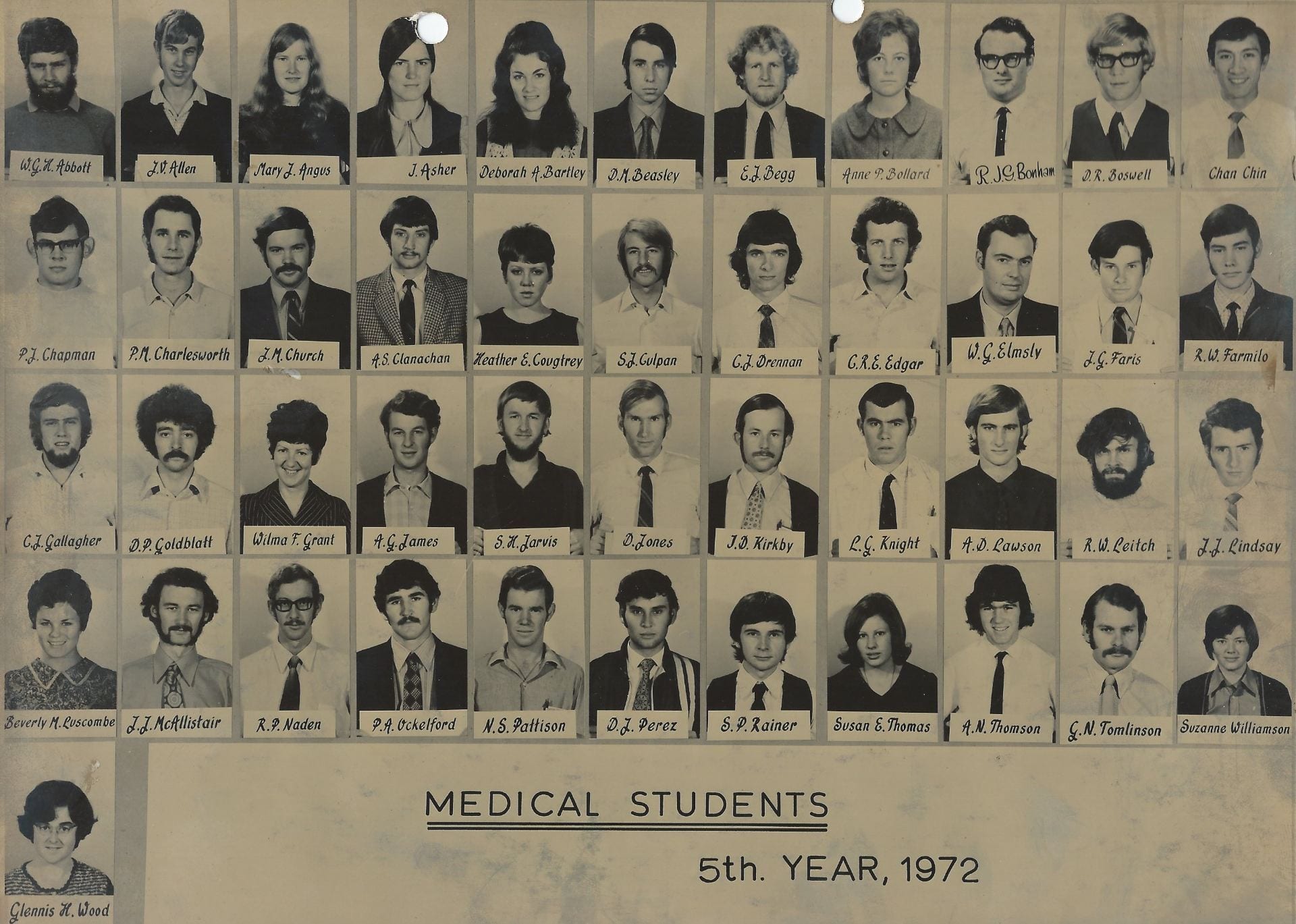

Ian Reid, clean shaven as a first year student in 1972 and in more familiar hirsute guise in 1975.

The medical student magazine Quack’s take on the selection process, 1977.

Female Students

When Waitemata MP Malcolm King drew the attention of Parliament to the pressing need for an Auckland Medical School in 1964 he spoke exclusively of `young men’ being admitted. This gender bias, conscious or otherwise, was occasionally raised in the early years of the school but had little impact on the entry of women to medicine at Auckland.

Looking back half a century later, the Medical School’s first appointed lecturer, Graham White, defended the composition of the 1968 intake:

It was a very male – the first class was very male-oriented, 80 per cent male. And that was because very few women applied. So there was no attempt at a gender mix of any kind at any stage…. It wasn’t true that we tried to limit the numbers of women. It’s just that they weren’t applying.

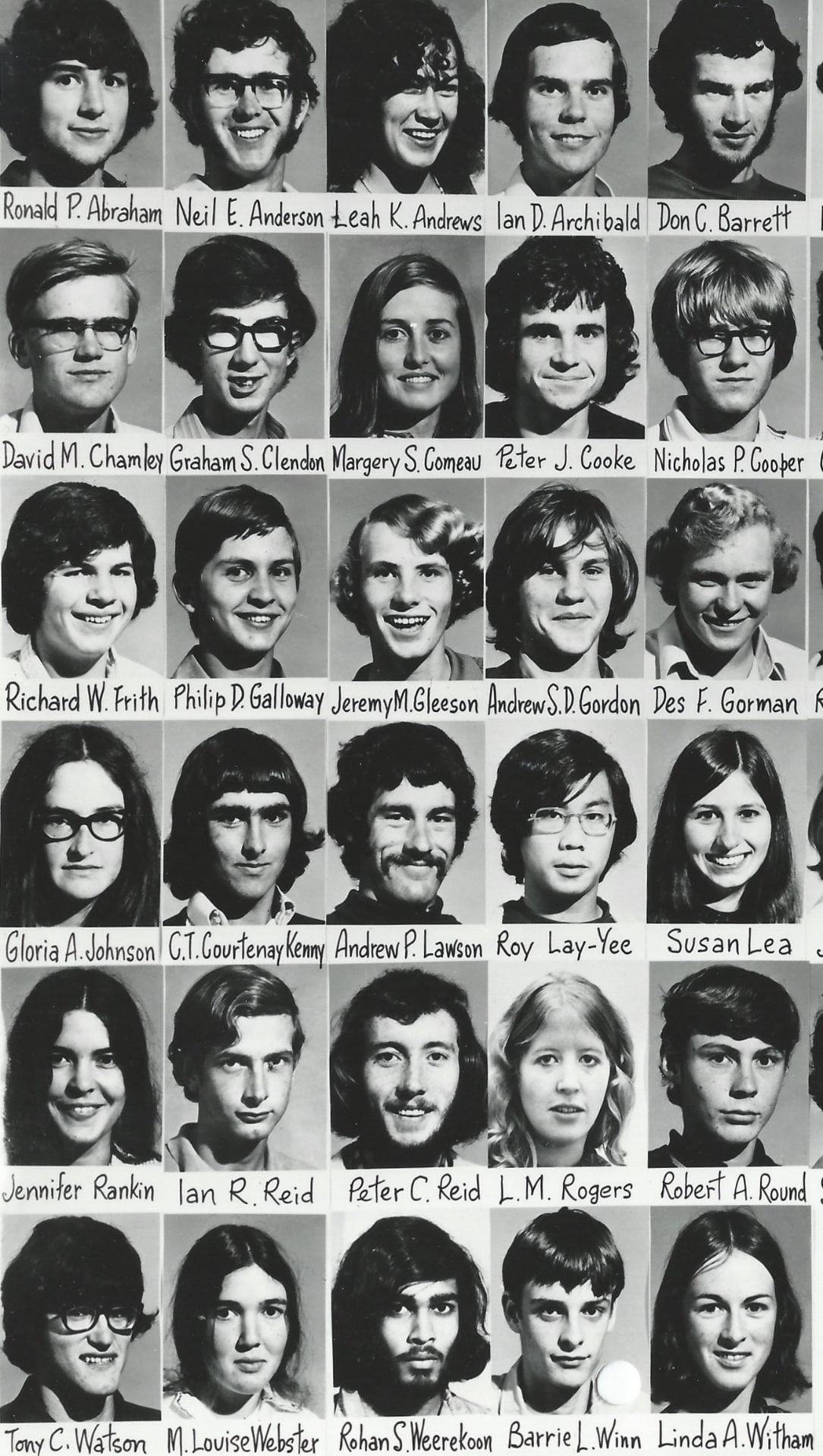

Ian Reid, who enrolled in the School in 1972’s fourth intake later described the `dinky little class, there were 60 of us’ with, in his recall, an almost even distribution of the sexes.

Ian Reid

Reid’s estimate was somewhat awry, as shown by the second year class `mugshots’ which displayed 48 males and 12 females, exactly the same balance as the 1968 intake.

In 1975 David’s Cole inaugural address as Dean supplied more accurate figures, revealing that women had made up 20 per cent of the intake in 1968, 42 per cent in 1974 and 30 per cent in 1975; at this time women made up only 13 per cent of names on the Medical Register. Four years later Acting Dean Campbell Maclaurin reported that 35 per cent of students were now female and drew attention to the recent award of Rhodes Scholarships to recent graduates Jane Harding (1977) and Jane Eyre (1978):

There is obviously something very special about the girls coming through this School which the Selection Committee recognises.

Virtual parity was achieved by 1987, with the University News commenting that there was still a need for a better pathway to specialist training to accommodate families.

Getting to this point had not been entirely straightforward. Dean Cecil Lewis’s insistence on admitting students solely on marks with no reference to subject facilitated what inaugural Professor of Psychiatry John Werry categorised as `a huge influx of women, because a lot of them were at girls’ schools where they didn’t teach Physics or anything like that in the seventh form.’ Ensuring that these girls survived the first year curriculum required Physico-chemistry lecturer Graham White to go the extra mile, an effort acknowledged by several of his former colleagues. Surgery Professor Eric Nanson then suggested the introduction of a quota to limit the number of female students because, according to John Werry, he believed that `everybody knows it’s a waste of time educating women because all they’re going to do is to get married and have children.’ The move was vigorously opposed by Dennis Bonham (Obstetrics) and Bob Elliott (Paediatrics) both of whom saw women as essential for the development of their specialties.

The growth in the percentage of female students detailed above must have given great satisfaction to former Dean Cecil Lewis who had reported after his term of leave in 1973 that:

It was gratifying to see British schools veering towards our practice relating to the admission of females to the medical course and to note the efforts of the health authorities there to provide suitable forms of medical practice after qualification for the pregnant [woman] and the mother.

Human Biology 2 `mugshots’, 1973.

The 1968 Intake: Male

In mid-1970 David Cole, the Associate Dean for Graduate Studies since 1967 and destined to become the longest-serving dean during the first half century of the School’s existence, wrote to the New Zealand Medical Journal about misrepresentations in the national press concerning wastage at medical schools. He explained that Auckland had hoped that around 50 of the 60 inaugural students would proceed to graduation. To date, with students now in their third year of study, the losses amounted to one who had transferred to behavioural science, with another withdrawing temporarily for health reasons; three had been required to repeat first year, with another 7 currently repeating second year.

In the event, only one of the 48 males in the 1968 inaugural Medical School class dropped out before completing his degree, a figure better than all predictions. When the first class graduated in 1974 34 of the males were present; 9 more followed in 1975 and another 4 in 1976.

The subsequent careers of this cohort of male students vindicated the selection and teaching philosophy promoted by Douglas Robb, Cecil Lewis and others. More than a quarter held academic posts at some stage, often at the highest level. Writing for the University Gazette in 1967 Lewis expressed the view that New Zealand should train enough doctors for there to be a net outflow to less fortunate countries, on humanitarian grounds. His vision was only partially realised in this initial group, more than 25 per cent of whom became long-term expatriates – but predominantly to Australia, Britain or North America, none of which qualified as less fortunate.

Bushy-eyed and bright-tailed: 57 members of the class of 1968 with Dean Cecil Lewis (centre) and some of their teachers. The non-presence of the remaining 3 students is a mystery.

The clean-cut appearance of 1968 was somewhat altered by the time the 1968 intake were 5th year students. Students of both sexes now dressed more casually and 13 of the males now sported facial hair, ranging from pencil moustaches to rampant side burns and full-face beards.

The 1968 Intake: Female

From the outset women seeking entry to medicine had additional hurdles to cross, not least of which was the interview prior to admission. In 1968 17-year-old Innes Asher was daunted by the sight of four men in black suits while Felicity Goodyear-Smith who began the course three years later also recalled `a whole lot of men in suits’ at what she described as `quite a gruelling interview’.

In Asher’s case she was thrown further off balance when she was asked how she was going to plan her family.

The first group of 12 women also faced what now appears an intrusive degree of interest from the local press. In September 1970 the New Zealand Herald reported criticisms of the Auckland Medical School `all because every fourth student is a woman’, and defended the policy as being in step with the times. The paper also quoted an Otago Medical School spokesman’s speculation that `perhaps the Auckland experience is merely a passing phase’. Some local doctors were equally sceptical, with a member of the Auckland executive of the British Medical Association arguing that while female applicants might have a short-lived advantage they were unlikely to `stand the pace’ set for their male counterparts.

Asked to comment, Dean Cecil Lewis argued there was no need to think about quotas or restrictions on female entry:

This school has been set up on the most liberal principles and it would be a great pity if we were forced to make a distinction on the grounds of sex – or any other grounds, for that matter.

His comment was somewhat at odds with Professor Bob Elliott’s recall that Lewis had warned interviewers against over-marking female candidates who were socially more mature and good looking; he apparently suggested that interviewers should `subconsciously deduct 10 per cent from whatever estimation you arrive at’. Elliott’s response to interviewing one of the four medical student daughters of future Dean Derek North showed how seriously he took the dean’s advice.

A second article in the Herald in November 1973 examined what the newly qualified women graduates intended to do during their internships. In 1970 one of those questioned, Beverley Luscombe, had mounted a spirited defence of the female students’ commitment to their careers:

It is not our objective to fill in time between leaving school and getting married.

By 1973 Luscombe had become the first of the class to marry, to a mature student, Gavin O’Keefe, who had just completed the first year of his own medical studies. Anne Bollard, another of those interviewed on both occasions, revealed that she was to marry her classmate Paul Ockelford after graduation with both committed to working in Rotorua for the next 12 months. A third, Sue Thomas, was about to wed an Australian geologist and head offshore for a year with a long-term view to undertake postgraduate training.

Of the 12 women admitted to medicine in 1968, three failed to complete the course. One withdrew in her final year because of prolonged ill-health; a second (Patricia Barr, now Cheel) decided orthodox medicine was not for her and has become an outspoken advocate for alternative therapies such as homeopathy, anti-vaccination and anti-fluoridation, standing for the mayoralty of Auckland in 2016 as a candidate for STOP (STOP Trashing Our Planet); a third, Jeannie Meyer, also dropped out.

Of the remainder, 8 graduated in 1974 and the last, doctor’s daughter, Suzanne Williamson, in 1975. In 1970 Innes Asher had declared her intention to enter general practice, an option exercised by about half the intake. In the event Asher became an academic paediatrician and two of her contemporaries had careers in obstetrics and gynaecology.

Sue Fleming (née Thomas), one of the two obstetricians, reflected on her working life in a 2015 interview, noting that she had been:

largely unaware of any barriers I might meet professionally because I was a woman. Perhaps this was because as a first graduating class we received special attention from our teachers or perhaps because it was the general optimism of the time. For me, this optimism was best captured by the Pointer Sisters’ hit song `Yes We Can’, and its lyrics that focused on building a better world through hard work and kindness.

Innes Asher on the Interview Process

Bob Elliott on interviewing Derek North's daughter

Drs Beverley O’Keefe and Anne Ockelford captured by a press photographer at their graduation ceremony in November 1973.

Sue Fleming returned to Auckland as Director of Women’s Health at the Auckland District Health Board 2013-17.

Auckland University Medical Students’ Association (AUMSA)

The transitory nature of membership of organisations such as student bodies means the collective memory often becomes blurred. The current AUMSA website proudly proclaimed in 2018 that `AUMSA has been around for 30 years’ but the origins go much further back, to the opening of the Medical School in 1968.

When the inaugural 60 students met for the first time in February 1968 they swiftly adopted the suggestion from Dean Cecil Lewis to form an Auckland University Medical Students’ Association. The original committee members, four males and one female, were Andy James, Beverley Luscombe, John McAllister, Peter Madill and Garry Tomlinson. Dr Wilton Henley, medical superintendent-in-chief of the Auckland Hospital Board, was elected as the first president, presumably with the guidance of Lewis who had worked closely with Henley over the previous two years in setting up the Medical School.

The Dean’s gesture was more than tokenism, with two student representatives – Innes Asher and Grant Gillett – invited to attend the first Faculty of Medicine meeting on 17 June 1970. The prevailing interest in seeking student views was recalled in 2017 by James Church, another of the 1968 intake who, like Asher and Gillett, ended up being appointed to a full professorship (in his case in the USA).

When Cecil Lewis resigned in 1974 Neil Watson paid tribute on behalf of the AUMSA, crediting him with being the prime mover in its foundation and with showing `dogged support’ for student involvement in committees. The Dean’s successor, David Cole, was eager to maintain good relations, with the medical student magazine Quack reporting in June 1975 that Cole was looking forward to continued cooperation with the Association, in the wake of the doubling of the student intake.

That same year two of the AUMSA representatives, Janet Eyre and Bruce Arroll, set up an Education Committee to prepare student submissions to Curriculum Committee. Within a few months it had 8 members, including Beverley O’Keefe (one of the first AUMSA committee members under her maiden name of Luscombe), alongside John Carman and Alistair Scott as staff consultants. Two years later Peter Black, now chairman of the Education Committee, provided an outline of the probable new clinical curriculum, in his role as student representative on the Faculty’s Curriculum Committee. Eyre, Arroll and Black all went on to occupy professorial chairs, two in Auckland and one in the UK.

While the AUMSA acted as a voice for the students it also served an important social function, beginning with the first annual dinner on 2 August 1968.

The menu for this first dinner offered fairly basic 1960s fare – fried schnapper, Chicken Maryland, and fruit salad and rum baba, with overtones of pretension in the `potage d’aujourd’hui’, and in the `café’ to round off the meal. The 1969 dinner was more ambitious. The Chicken Maryland was still there, but so too were shrimp cocktail, oyster cocktail, filet mignon, and Peach Melba. `Coffee’ on this occasion was accompanied by cigars, all washed down with red and white wine and Benedictine liqueur.

In addition to the dinners, the AUMSA organised annual balls. On at least one occasion the ball was greatly enhanced thanks to the presence of Jenny Corban, who went on to become a Hastings paediatrician. Former AUMSA office-bearer Peter Charlesworth recalled in 2017 that:

Her father was one of the Corbans of Corban’s Wines. I remember arranging through her to get a really special deal on a whole lot of wine to provide for the medical students’ ball.

These social events, certainly in the early years, were not restricted to students. In the diary which he kept throughout his undergraduate years, 1968 entrant Steve Culpan expressed his delight at the intermingling of staff and students which he witnessed at the first medical ball.

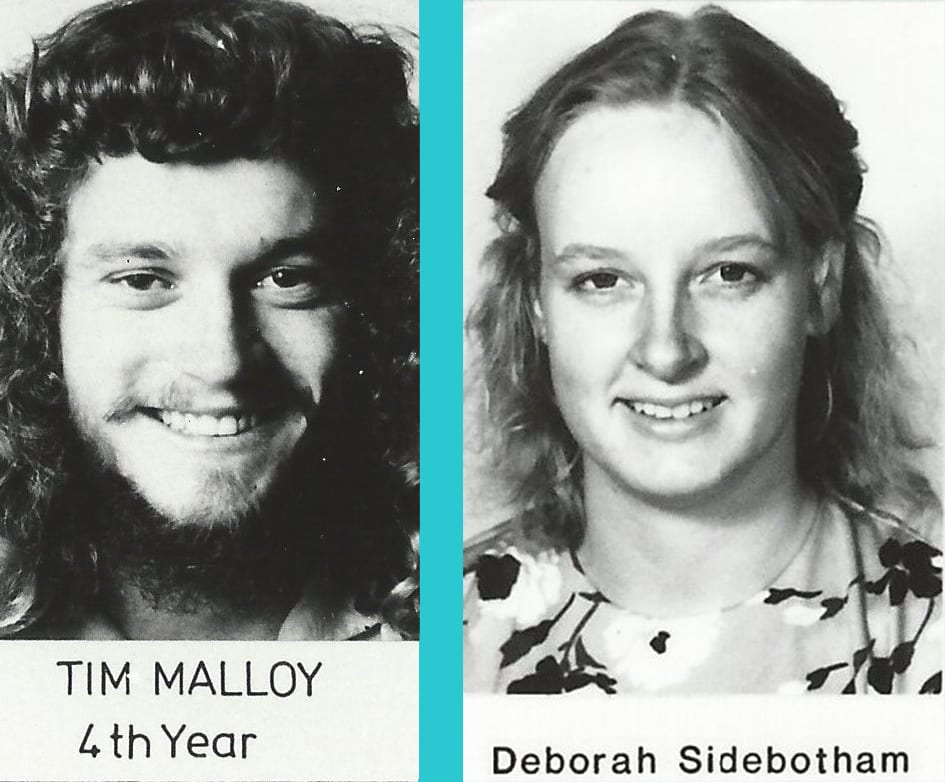

In addition to its executive members, the AUMSA committee included social and sports’ `controllers’ and class representatives. Over the years many students cut their political and administrative teeth in one or other of these roles. Tim Malloy, for example, a 4th year representative in 1977, went on to become President of the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners 2012-18. In 1985 brothers Andrew and Chris Wong both served on the committee. Chris was Vice-President in 1986 and went on to become a Rhodes Scholar; Andrew occupied the presidential role in 1987. Two of the 1988 committee went on to pursue very different careers. Jonathan Coleman was Minister of Health 2014-17 while AUMSA Secretary Jonathan (`Jon’) Masters has built a high profile as `The Vasman’.

Arguably the most influential former AUMSA committee member, however, is Deborah Sidebotham, a class representative in 1983. After graduating in 1987 she became President of the Resident Doctors’ Association, resigning in August 1988 to assume the role of Executive Officer, a post she has filled for the past three decades under her married name of Deborah Powell.

The Freshers’ Camp

With the doubling of the Medical School intake from 60 to 130 in 1975, it became harder to establish the same esprit de corps which had marked the first few years. The solution, arrived at after a visit to Australia by Dean Cole and third year student Janet Eyre, was the introduction of a student camp. As physico-chemistry lecturer Graham White, who mentored more than 3000 students during his term of office, explained to student magazine Quack in 1976, the first camp dispelled any concerns that:

the friendly, personal atmosphere which has characterised our courses in the past would now give way to a coldness so often associated with the teaching of large undergraduate classes elsewhere in the University

The student leaders of the inaugural camp in 1976 were Janet Eyre and Bruce Arroll, both of whom went on to have successful academic careers. Eyre became a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford in 1978 and was appointed to the Chair of Paediatric Neuroscience at Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1992, one of the earliest Auckland graduates to reach the professoriate. Arroll, after spending time in Canada, returned to the Department of Community Health at Auckland and was elevated to a personal chair in the Department of General Practice in 2005.

In 2017 Bruce Arroll recalled with fondness the background to that first camp, and what it had meant to the school in over the ensuing decades.

Bruce Arroll

AUMSA publications: Quack and New Doctor

Like many student publications, the AUMSA magazine has had a somewhat precarious existence over the past half century. In June 1975 the new editor, Gavin O’Keefe, explained that the students were keen to revive Quack after a three-year hibernation, in order to restore the `unusual sense of closeness between staff and students [and] their mutual sense of discovery in creating a course’. O’Keefe pointed out that this camaraderie had inevitably been diminished now the school had a full complement of students in place of a single class, and with the doubling of the first year intake which was to come into effect in 1976.

Over the ensuing years Quack acted as a conduit for information, covering topics such as curriculum development, the student selection process, number of enrolments, and the growing links with what one 1978 correspondent described as `Polynesian health care’.

In the late 1980s Quack adopted a title which better reflected its target audience – New Doctor. For some it was a sign of growing maturity and a departure from any perceived frivolity. In 2018 the AUMSA website described New Doctor as `the notorious medical school magazine’: it has always offered far more than that.

The AUMSA committee, 1969: Wilma Grant, John Goldsmith, John Keir, Innes Asher, Douglas Robb (President), Peter Charlesworth, Rowan Macnaughton, Paul Ockelford, Beverley Luscombe, John Faris.

James Church

The venue for the first AUMSA dinner in 1968, presided over by Dr Wilton Henley, was decidedly austere.

The 1969 dinner was more upmarket, with white tablecloths and a carpeted dining room. The interaction of students and staff is clearly shown with Innes Asher seated next to physico-chemistry lecturer Graham White and opposite Associate Dean David Cole and University Registrar Jim Kirkness. The three male students appear to be engrossed with events at another table.

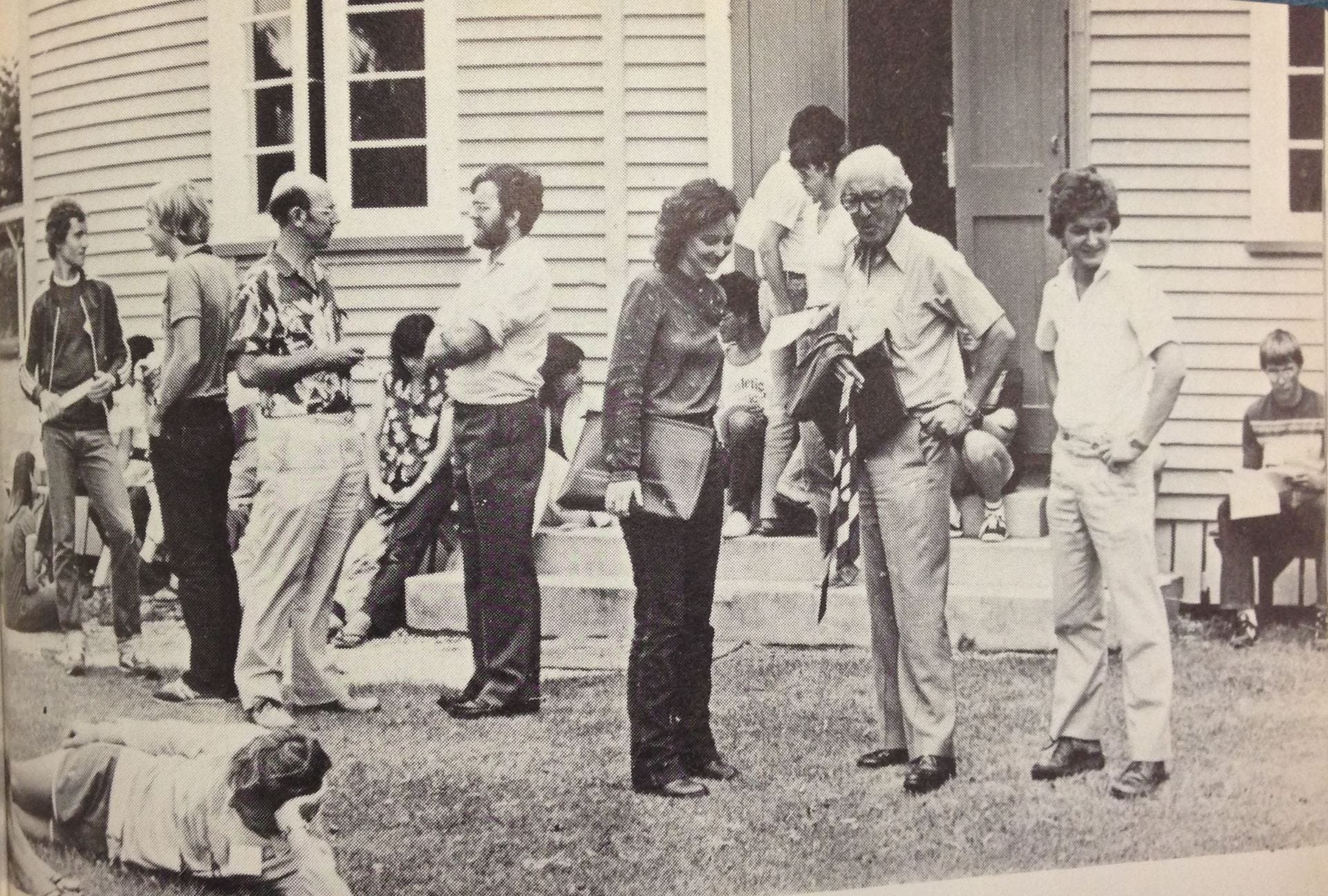

Janet Eyre, described by the University News in 1982 as `a lively medical student’ returned from Oxford in 1982 to talk to the freshers gathered at the three-day camp held that year at Eastern Beach in Howick. Here she is seen chatting to Dean David Cole. The figure standing next to Cole is another of the organisers, Graham Witney MB ChB 1983, who was about to head off on his elective to Tanzania. Witney has worked as a GP in Howick since 1990.

Quack’s unnamed cartoonist in 1979 expressed signs of frustration that communication between students and staff was not entirely satisfactory.