THE DEANS

This section incorporates short biographies of the seven Deans appointed to head the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences from its inception.Appointing the First Dean

Selecting the inaugural dean for the Auckland Medical School was clearly a critical decision. As Chancellor of the University of Auckland from 1961, Douglas Robb had a considerable influence on the evolution of the medical school, including the search for a dean. His active interest in Auckland medical education dated back to the formation of the Postgraduate Medical Committee in 1943 and his voluminous correspondence files contain discussions on the topic with colleagues in New Zealand and overseas, some of which had a bearing on the outcome of the search.

It appears there was only one local candidate in the running in 1965. Dr Michael Gilmour, a physician, had been medical tutor of the Auckland Branch Medical Faculty of the University of Otago from 1954-6, later becoming sub-dean. In 1965 he was named by the Auckland Star as the future dean, apparently on the say-so of someone on the University Grants Committee.

Jack Sinclair on Michael Gilmour

It was also rumoured that Gilmour had the support of Vice-Chancellor Kenneth Maidment, who was one of his patients.

Robb, however, set his sights more widely. In the late 1940s he began corresponding with Dr Wendell Macleod, Dean of the University of Saskatchewan in Canada 1952-62, who was known as the `Red Dean’ because of his progressive views on social medicine and medical education. The two men met in person at the 1959 World Congress on Medical Education. Saskatchewan’s Foundation Professor of Surgery from 1954-70 was the New Zealander Eric Nanson, who was informed by Robb in 1965 about the forthcoming deanship. Robb conceded that the conditions would seem `pretty thin to you’ and Nanson replied, turning down the prospect on salary grounds.

As early as 1947 Robb had also taken an interest in the proposal to set up a medical school in Perth, Western Australia, writing to the superintendent-in-chief of the Auckland Hospital Board about his belief in the parallels between Perth and Auckland. It is no surprise then that Robb encouraged Perth’s foundation Professor of Surgery, Cecil Lewis, to apply for the Auckland deanship. The fact that Lewis had previously lectured at Cardiff, Britain’s youngest medical school at the time, was an added bonus.

Lewis, an eloquent Welshman, was duly appointed and took up the mantle of Dean of Medicine in 1966. As the University News reported in June 1974, on the eve of his departure for pastures new:

In 1966 the School of Medicine consisted of one modest house, complete with geranium-filled window boxes, and a collection of contentious plans.

Cecil Lewis (1918-2006) was in many respects an inspired, and certainly a bold, choice as first Dean of the Auckland Medical School. After serving in destroyers in World War II, Lewis, the son of a Welsh clergyman, lectured in anatomy and surgery at the medical school in Cardiff before accepting a post at the new medical school in Perth, Western Australia.

A larger-than-life character, Lewis was a musician and artist, and at one stage had worked as a circus roustabout and strongman. This polymathic approach coloured his approach to medical education and to the students under his care. As Professor Innes Asher, one of the first intake of students to Auckland in 1968, recalled, Lewis wished to produce well-rounded and multi-faceted graduates.

Innes Asher on Cecil Lewis

Lewis was extremely eloquent; as Bob Elliott, the first professor of paediatrics put it, `he had the marvellous Welsh oratory’. Students also appreciated his approachability, and his command of language. Steve Culpan, one of the original 1968 intake, recalled this in 2017:

He was an idealist, he was always smiling and he had his head slightly in the clouds, and he was a great talker.

This eloquence stood Lewis in good stead as he set about promoting his vision for the future. His inaugural lecture in April 1966 outlined the three responsibilities of a medical school – teaching, research and `a more recent duty [a] direct contribution to the affairs of society’. In a follow-up in the New Zealand Medical Journal he explained his desire to correct the imbalance between hospital and community practice training, partly through setting up a model general practice, and the introduction of a 46-week year. He also cited the example of the Hadassah Medical School in Jerusalem, which employed medical sociologists, as a way of meeting the obligations to society.

Other innovations included the concept of a chair in the `medicine of Polynesian peoples’, as Professor John Werry phrased it. Above all, he wanted students to think for themselves, as he explained in 1967:

But the subjects are not as important as the general concept, which is to introduce into the student’s mind a spirit of enquiry, to train him in research method, and to give him some insight into the basic patterns of human behaviour.

For many of his colleagues, Cecil Lewis’s Achilles heel was his lack of organisation and failure to pay sufficient heed to detail. Physiology professor Jack Sinclair was taken aback to learn that Lewis had absented himself from a Medical Research Council funding meeting to discuss the Auckland budget for the next three years in order fulfil an engagement to talk to `the wives of the Albany rose-growers’. Conversely, this commitment to the community was one of his strengths and his ability as a communicator enabled him to solicit external funding to implement his vision. One outcome of this was the setting up in 1972 of the Department of Community Health, described at the time by Steven Culpan in his student diary as `something of a milestone in medical education as such a department has never existed before anywhere in the world’.

Forward-looking was the perception of many who came into contact with the Dean during his nine years in Auckland. In the words of Bruce Arroll, one of the early students who went on to occupy a chair in the medical school, `it felt like the cutting edge, it felt like a good place to be, and I was glad that I was at Auckland rather than Dunedin’. Another student, current Deputy Dean Distinguished Professor Ian Reid, has recently commented that `the Faculty was so small at that time that even as a first-year student you sort of knew who the Dean was’. Early staff members were equally impressed with Lewis’s foresightedness.

In 1974, not long after the first cohort of students completed their studies, Lewis suddenly announced his departure, in keeping with his philosophy of never staying in a post for more than a decade.

The legacy which he passed on to his successor is perhaps best expressed in his own words in the November 1967 issue of the University Gazette:

There is then placed upon us an obligation to produce something more than a medical school of mediocrity.

Dean Cecil Lewis planting a plane tree from Cos, representative of Hippocrates, just prior to his departure in June 1974. The figure in the centre was Professor David Cole, his successor as Dean.

Graham Vaughan on Cecil Lewis

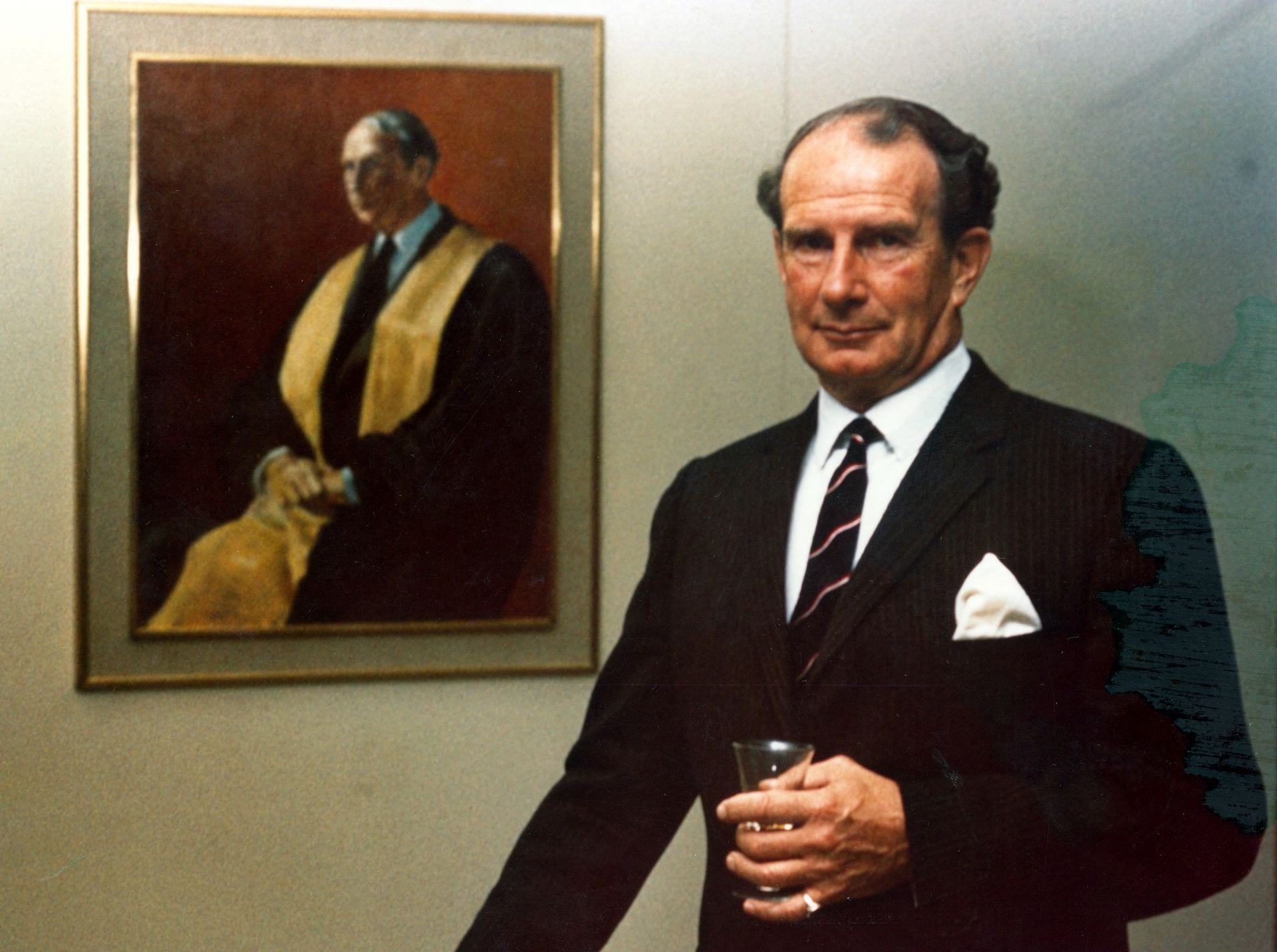

David Simpson Cole: Dean 1974-89

At Cecil Lewis’s farewell in June 1974 David Cole (1923-2008) spoke as the `selected successor’. Cole’s parents were both Auckland doctors, trained in Edinburgh and London respectively. David himself graduated from Otago in 1948 then went to London to train as a thoracic surgeon at the Brompton Hospital. On his return to New Zealand he worked at Green Lane Hospital under Douglas Robb and Rowan Nicks and, later, Brian Barratt-Boyes. Robb quickly became a mentor, encouraging Cole to become involved in medical education, initially through the Postgraduate Medical Committee set up in 1943. This connection was fostered by the fact that Cole’s father had been one of Robb’s co-authors of A National Health Service (1943).

In 1957 Cole became secretary of the committee, a role formerly held by Robb, who predicted in his 1967 autobiography that:

In due course, the Post-Graduate Committee will become part of the Faculty of Medicine when that is set up.

Cole also helped develop education programmes for the National Heart Foundation set up in 1958, was on the University of Auckland Senate Medical Advisory Committee from its formation, and became associate dean for graduate studies in November 1967.

After the heady years of excitement under Cecil Lewis the Medical School needed to consolidate and to expand. David Cole was the ideal candidate to provide this. As physiologist Jack Sinclair later observed:

He cleared up all the untidy things left by Cecil Lewis. After that he was running it on a day-to-day basis.

Although there were rumours about Cole’s temperament, these were firmly refuted by another ex-colleague, inaugural Professor of Paediatrics Bob Elliott.

Cole’s 1975 inaugural address addressed the forbidding prospect of a doubling of medical student numbers from 60 to 130, something which he feared might diminish the personal element. He also revealed a willingness to look to the future, announcing that the monitoring of the medical course was to be handed over to a newer and younger curriculum committee `largely purged of the original planners’. Five years later, with the medical curriculum again under study, he was quick to point out in a University News interview that he did not share the concern expressed by a few of the staff about the School’s philosophy or teaching patterns. At the same time, as he had explained to the graduating class of 1973, they were entering a profession which `has infinite opportunities for the development of your talents’, but also one in which there was a necessity for lifelong continuing education.

David Cole always had an affinity for the student body, a trait which first emerged in his final year as a student when he initiated the revival of the capping concert at Otago. As Dean, he was a conscientious mentor who maintained a detailed card index of students. They in turn regarded him as `an affable and very positive role-model’, in the words of current Deputy Dean Ian Reid. This regard also shone through in the cartoons which appeared in the medical student magazine Quack.

After retiring in 1989 Cole continued his long-standing interest in medical ethics, acting as part- time executive officer of the Medical Council, and gave a number of papers on related topics to the Auckland Medical History Society of which he was president for a term. Living up to his address to the 1973 graduates on lifelong education he was also very active in the evolution of U3A (the University of the Third Age) which extended from its European origins to New Zealand in 1989.

David Cole’s contribution to Auckland medical education for over half a century can be summed up in the words of another former colleague, Sir John Scott, speaking in 2008.

John Scott on David Cole

Bob Elliott on David Cole

Dean Cole leading a procession of his protégés. Konrad Lorenz was the Austrian zoologist and ethologist who devised the theory of imprinting which described how some birds bond with the first living thing they see after hatching. Cole was a regular target for Quack cartoonists.

John Derek Kingsley North: Dean 1989-92

When David Cole retired from the deanship in 1989 Vice-Chancellor Colin Maiden was disappointed by the response when the post was advertised and shoulder-tapped Derek North (1927-2016), who had been born just four years after his predecessor, to fill the vacancy.

The appointment was not quite an apostolic succession but North was his predecessor’s brother-in-law, with Cole married to his twin sister.

On completion of his Otago medical degree North had been selected as a Rhodes Scholar, a distinction he shared with the Vice-Chancellor himself and with Auckland Hospital superintendent-in-chief Wilton Henley, who played a leading role in the establishment of the school. Following his return to Auckland North acted as medical tutor to the Auckland contingent of the Otago final year students from 1957-9, then became physician in charge of the Medical Unit at Auckland Hospital, with a remit to establish a research presence. In 1966 North was appointed foundation Professor of Medicine in the fledgling Auckland school.

The high standards set by North were daunting for some students and staff but did provide a solid academic grounding. In partnership with Eric Nanson, the professor of surgery, he produced a small volume of clinical signs, distributed to students at the beginning of their fourth year. John Faris, one of the 1968 intake of students, later recalled the impact this had:

And this is not too long after Chairman Mao had been around, so the book was rapidly called `The Thoughts of Chairman North’!

By the time Derek North was appointed Dean in 1989, four of his daughters had followed him into medicine, and prior to his retirement in 1992 he was able to welcome the eldest, Robyn, onto the staff as a senior lecturer in obstetrics and gynaecology.

During his relatively short tenure, North was assisted by recently-appointed assistant registrar Sue Cathersides, who had first joined the Medical School a decade earlier as his research associate. Given his age, Derek North’s appointment was something of a stopgap, entrusting the Medical School to a safe pair of hands until a long-term solution offered itself. His contribution to the evolving school, however, extended far beyond his deanship. As Sir John Scott commented when North retired he had been:

one of a talented group who seized the initiative and applied the available resources through intelligent planning, such that the Medical School, teaching hospital complex at Park Rd emerged as an outstanding centre for medical learning in the South Pacific.

Colin Maiden on Derek North

Peter David Gluckman: Dean 1992-2001

Peter Gluckman (b. 1949), the son of an Auckland psychiatrist, completed his medical degree at Otago in 1971, after spending his final year in Auckland with the Auckland Branch of the school. The decision to focus on paediatrics came early in his career, with mentoring from two University of Auckland staff – Bob Elliott, the inaugural Professor of Paediatrics, and David Lines, appointed to a research chair in child health in 1973.

After four years postdoctoral study in America Gluckman returned to Auckland in 1980 to run a research group funded by the Medical Research Council, and also acted as provisional chair of the Association of Researchers in Medicine and Biomedical Sciences when it was formed in 1986 as a result of concerns over declining funding for health research. Two years later Gluckman became Professor of Paediatrics and Head of Department in recognition of his research contribution.

When Derek North retired in 1992 the University looked to strengthen the research side of the school. One of the three short-listed candidates was Noel Maclaren, a paediatric endocrinologist who had gone overseas after completing his degree at Otago in 1963 and had trained at London’s Great Ormond Street, Johns Hopkins, and the University of Maryland. For whatever reason, none of the candidates were considered entirely suitable and Vice Chancellor Maiden again targeted an internal appointee. Peter Gluckman, another paediatric endocrinologist, was regarded as cutting edge in research terms, As Maiden explained at the time:

Peter, we’ve got a great teaching Medical School, I don’t have a research-intensive Medical School. The reason I want you to be Dean is to create a research-intensive, politically strong Medical School.

Changes to the structure of the new Health Research Council, which saw Gluckman faced with the loss of almost 80 per cent of his salary, helped sway his decision to accept the offer. As he stated in a 2017 interview: `It was a no-brainer to become Dean!’ In becoming Dean Gluckman had to face up to a number of challenges, including the long-serving Dean’s secretary, Jan Bowman, who turned out to be a tower of strength.

He also received sage advice from Derek North, who urged him to negotiate control of the reconciliation fund, as a result of which, he later revealed, the Medical School became `the first bit of the University to get any level of financial autonomy’. Achieving a degree of financial security was also boosted by the arrival of John Hood as Vice-Chancellor in 1998.

With Hood’s encouragement, Gluckman set about restructuring the Medical Faculty into a Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, the first stage of which was creating schools of Medicine and of Biological and Health Sciences. By the end of the Dean’s tenure in 2001 Pharmacy and Nursing had also been added to the mix.

Speaking at the time of the 25th anniversary in 1993, Peter Gluckman envisaged the School of Medicine would have up to 2000 students and 800 academic, research and general staff by 2000, with an expanded research function. By the time he stepped down in 2001 there were approximately 2300 equivalent full-time students, the institution had basically tripled in size in just nine years, and Auckland’s share of health research funding had risen dramatically.

Assessing his performance in a 2017 interview, Gluckman had this to say of his term of office:

We didn’t have any significant scandals during the time I was Dean. There were the usual problems of individual staff members getting into some concerns of a personal nature, but they were well-managed and I don’t think there were any particular disasters. We didn’t have bad press during the time of my Deanship. The relationship with Otago was constructive. The relationship with the Hospital was on a fast rise. I was pleased about everything.

Bob Elliott on Peter Gluckman

Peter Gluckman on his appointment

Peter Gluckman on Jan Bowman

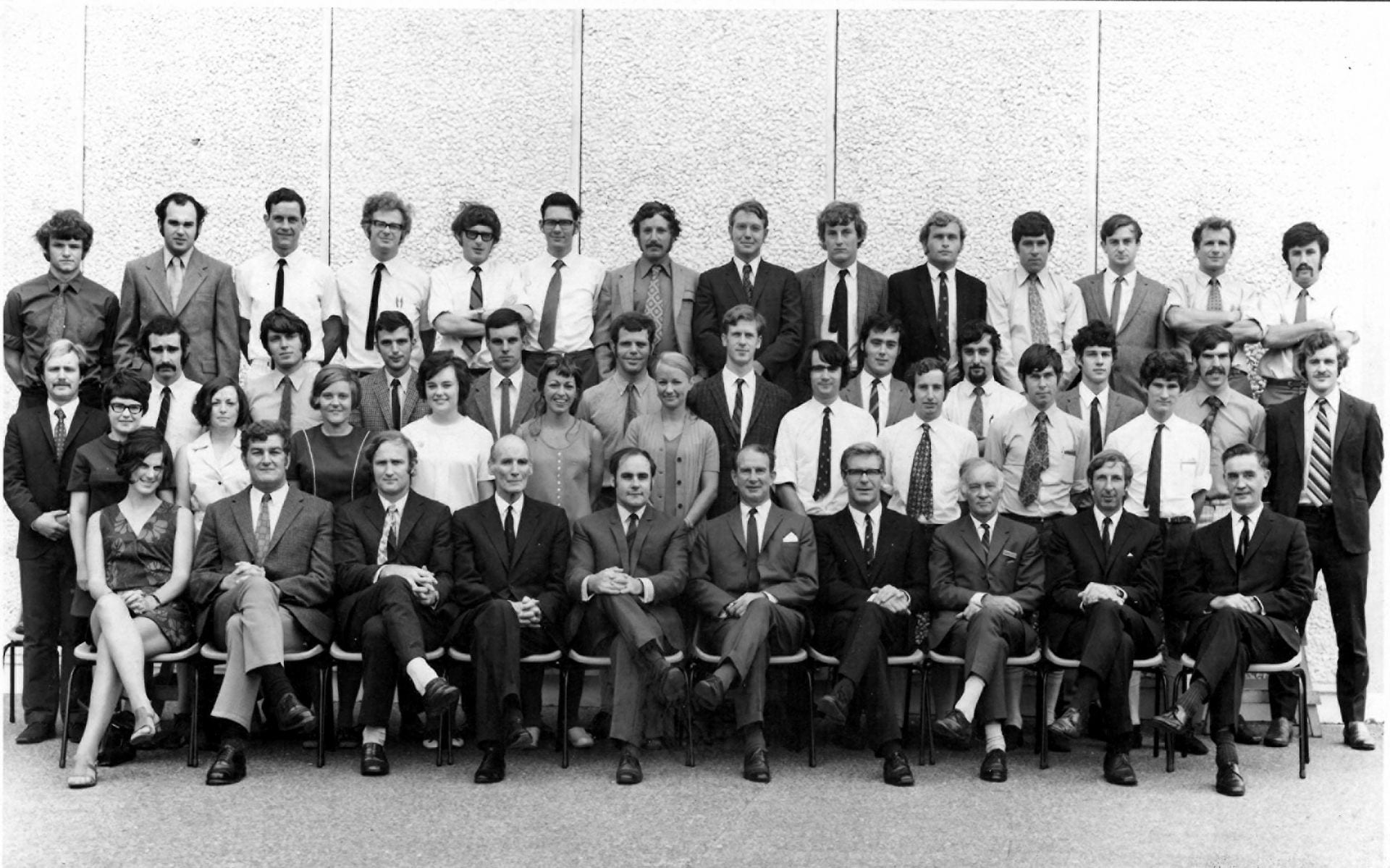

The first four deans, lined up in chronological order, at the 25th anniversary celebrations in 1993.

Peter John Smith: Dean 2001-5

Peter Gluckman’s replacement in 2001 was another paediatrician, the Australian haematologist and oncologist Peter Smith, who was persuaded to leave his position as Stevenson Professor of Paediatrics in Melbourne to come to Auckland. Smith, who had collaborated with New Zealand colleagues since the early 1990s and had undertaken work for the Medical Research Council of New Zealand, wished to extend the already strong biomedical research element in Auckland.

Smith’s appointment was initially welcomed by Gluckman, who praised his strong research, clinical and teaching experience, but there were later tensions in the relationship between the two men over the status of the new Liggins Institute, which was initially run as a division of the School of Medicine before it was accorded a greater degree of independence.

During Smith’s tenure the Faculty was separated into five distinct schools – Medicine, Biological and Health Sciences (later renamed Medical Sciences), Nursing, Pharmacy, and Population Health. The new Dean had identified population health as a priority when he arrived in 2001, regarding the projected move to Tamaki as a particular advantage to community health groups. Two years later he expanded on this theme to the alumni magazine, Ingenio, describing the School of Population Health as a new fence at the top of the cliff and an entity which would to combine research, teaching and learning about the health of whole communities, thereby making Auckland `a microcosm of the health issues facing New Zealand’.

In 2005 Dean Smith announced his intention to return home to Australia as head of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of New South Wales, with the incentive of masterminding a $900m redevelopment. Prior to his departure the Dean announced he would donate $250,000 as a parting gift, to fund a travelling fellowship to strengthen links between Auckland and the leading Australian medical schools and affiliated research institutes, adding that he would `look forward one day to welcoming a Fellow recipient to the Faculty of Medicine at the University of New South Wales’.

Smith was Dean of UNSW until he retired in 2015, the same year in which he completed a three-year term as president of Medical Deans Australia and New Zealand.

John Fraser on Peter Smith

Iain Martin: Dean 2005-11

In 2005 40-year-old Iain Martin became Auckland’s second Welsh-born medical dean. Born in Newport and trained at the Leeds Medical School, Martin was appointed to a chair in surgery at Auckland in 2000. Five years later Vice-Chancellor Professor Stuart McCutcheon welcomed Martin to the deanship:

After an extensive international search, we were pleased to discover that the best candidate was right here `at home’. Iain has a very strong research background, an international reputation as an academic surgeon, and has successfully led the School of Medicine through a crucial time in its development. He will provide strong academic leadership to the Faculty and continue to build its relationships with external agencies.

The University News described the 40-year-old’s rise to become Auckland’s youngest dean as meteoric, noting that, as head of the School of Medicine in 2004, he had overseen its re-accreditation. His declared intent was to establish Auckland as `the’ health faculty in New Zealand, to which end the priority for the ensuing five years was the refurbishment of the Grafton buildings, especially the laboratory facilities. He also saw the Northland Regional-Rural Medical programme come into effect in February 2008, something which he regarded as one of the highlights of his reign to that point.

By March 2009 the University had approved the redevelopment plans, but the endeavour took its toll. Just weeks later Martin underwent emergency surgery during a family holiday in Queensland. He returned later that month, `cheerful but still rather frail’ and was back at work by late May, wryly commenting in his Dean’s Diary:

As a general surgeon by clinical training, it has been a salutary experience to undergo a laparotomy for a large intra-abdominal abscess resulting in E Coli sepsis. Being on the other end of a scalpel certainly makes you appreciate both the science and art of good clinical practice!

Within weeks he was photographed at his desk, proudly showing off concept drawings for the ambitious redevelopment.

Martin was not around to see these plans come to fruition. In September 2011 he relinquished the dean’s role to become Deputy Vice Chancellor Strategic Engagement, in which role he signed a memorandum of association in December 2011 formalising the 30-year relationship between the University and Freemason’s New Zealand.

By mid-2012 Martin was on the move again, accepting the post of Vice President and Deputy Vice Chancellor (Academic) at UNSW, where he renewed his links with his predecessor, who was the current Dean of Medicine there.

After 16 years in Australia and New Zealand Martin jumped at the chance to return to the UK in March 2016 as Vice-Chancellor of Anglia Ruskin University, where one of his roles has been to oversee the creation of Essex’s first school of medicine, scheduled to open in September 2018.

Iain Martin summed up his Auckland experiences in the following words, at his leaving function in September 2012:

It was fantastic to be able to use the new Grafton atrium for my leaving function on Wednesday. The building developments are a very obvious statement of the changes that have happened over the past 6 years. However, the buildings are simply enablers and it is the people who work and study in the Faculty that really make the role special. The quality and range of activities that take place across the Faculty are simply incredible.

John Fraser on Iain Martin

A `fisheye’ view of the redeveloped Grafton complex, 2012.

John D Fraser: Dean 2012-

When John Fraser was appointed Dean of the FMHS in 2012 he broke the mould on two counts; he was the first Auckland graduate (PhD in biochemistry 1983) to hold the post and also the first non-clinician. Interviewed in 2017, Fraser revealed that he had long-standing, albeit tenuous, links with the Auckland Faculty. Two of his friends had been admitted to medicine straight from school and `this was my very first introduction to the Grafton medical campus, when I came to visit them as first year students staying at Grafton Hall of Residence – which has just been demolished’.

When the deanship became vacant in 2012 Fraser did not immediately consider the position since Auckland had traditionally appointed clinicians, though he was aware that several Australian deans were non-clinicians. He was then encouraged to apply by a number of colleagues and did so after reflecting on the fact that the Faculty had expanded to embrace a number of diverse schools. Given the substantial changes of the previous decade, Fraser, who had been head of the School of Medical Sciences since 2003, also felt it was pertinent to have a familiar face in the role.

In his first Dean’s Diary John Fraser reminded his readers he had been a faculty member for years and outlined his view of the future:

Since my appointment a number of people have asked me for my vision, to which I can only reply that it is the same vision that we all share, to be a faculty that is recognised nationally and internationally for its commitment to health issues, outstanding people, programmes, research and facilities.

Reviewing events at the end of the year, the Dean confirmed that `Although very demanding, I have thoroughly enjoyed my first 10 months as Dean…. My own personal highlight was the joy of seeing my daughter Ashley qualify in medicine this year.’ He did not refer back to his interview with the New Zealand Herald in March of that year when he admitted that his daughter, then a sixth year medical student, liked to remind him that, unlike her father, she would soon be a clinician.

During a 2017 interview John Fraser commented that the Faculty had grown from strength to strength and he was intending to accept a second five-year term. The sentiments which he had expressed to the Herald in 2012 apparently still applied:

The secretary knocks, our time is up and John is off to another meeting. The pace doesn’t seem to bother him. `So far it’s been pretty exciting but full on. I’m really enjoying it’, he beams.

Former Dean Iain Martin (second from left), current Dean John Fraser (centre) and Prime Minister John Key at the opening of the redeveloped Grafton Campus on 3 July 2012. Fraser commented in the next issue of the Dean’s Diary that: `The event went very well despite a momentary interruption by several noisy protesters, and if their spelling of the word “drowning” is any guide, we can say with some confidence they were not from FMHS.’